By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

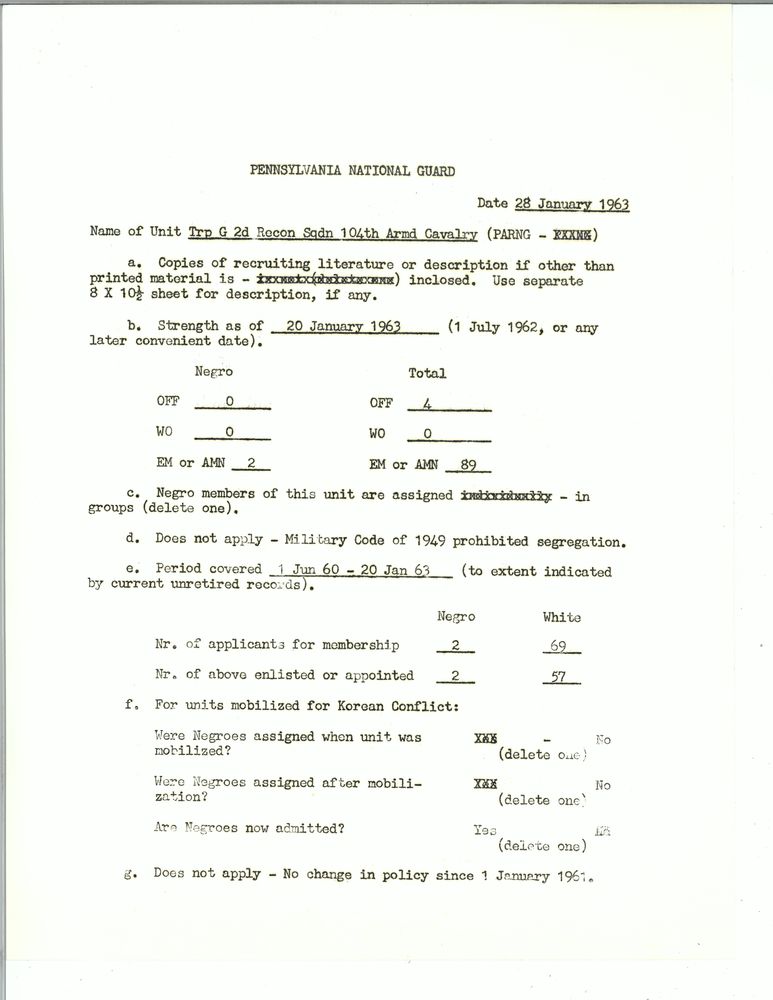

In 1948, President Harry Truman signed an Executive Order to end racist segregation in the United States military, which had discriminated against Black and Asian American service members even as they fought in World War II. President Truman’s order promised “there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services,” but more than a decade later, many Black Americans still couldn’t access equal housing, services, and promotions while in the military – and in some states, weren’t recruited at all.

GAGPP-002-001-p0075. Recruiting material for the U.S. National Guard’s Officer Candidate School. Gerhard Gesell Personal Papers, Box 2, “National Guard recruiting material: General (1 of 2 folders).” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

In June 1962, President John F. Kennedy created the President’s Committee on Equal Opportunity in the Armed Forces “to eliminate this source of hardship and embarrassment for the members of our Armed Forces,” and appointed a lawyer with a long civil service resume – Gerhard Gesell – as its Chair. Better known as the Gesell Committee, the new group was charged with investigating reports of racism across military branches, and creating a report with recommendations for the government to act on.

Both Gesell and the Committee’s Staff Director, Laurence I. Hewes III, went on to donate their Committee papers to the JFK Library, where archivists recently digitized them for free online access as part of the National Archives and Records Administration’s reparative digitization and description initiatives.*

In addition to Gesell and Hewes, the Committee was staffed with lawyers, veterans, and Black community leaders, including:

- Nathaniel S. Colley, attorney for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); World War II Army veteran

- Abe Fortas, attorney and member of the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity

- Louis Hector, attorney, formerly of the U.S. Department of Justice

- Benjamin Muse, journalist and head of the Southern Regional Council’s Southern Leadership Project; World War I and World War II veteran

- John H. Sengstacke, Publisher and Editor of the Chicago Defender, an influential daily Black newspaper

- Whitney M. Young, Jr., Executive Director of the National Urban League; World War II Army veteran

Formed as a “shirtsleeve Committee,” the members and their small staff only met in person a few times. Instead, they focused on gathering data and traveling to bases to talk with service members and commanders about their experiences, with Gesell and Whitney Young, Jr. often teaming up for these “field trips.” They also sent out questionnaires and collected records from military branches to investigate discrimination in recruitment, assignments, and promotions, as well as in restaurants, schools, and facilities in communities near military bases.

On June 13, 1963, the Committee published its initial report, titled “Equality of Treatment and Opportunity for Negro Military Personnel in the United States,” but quickly nicknamed the “Gesell report.” In describing the overall experiences of Black service members, the Committee wrote:

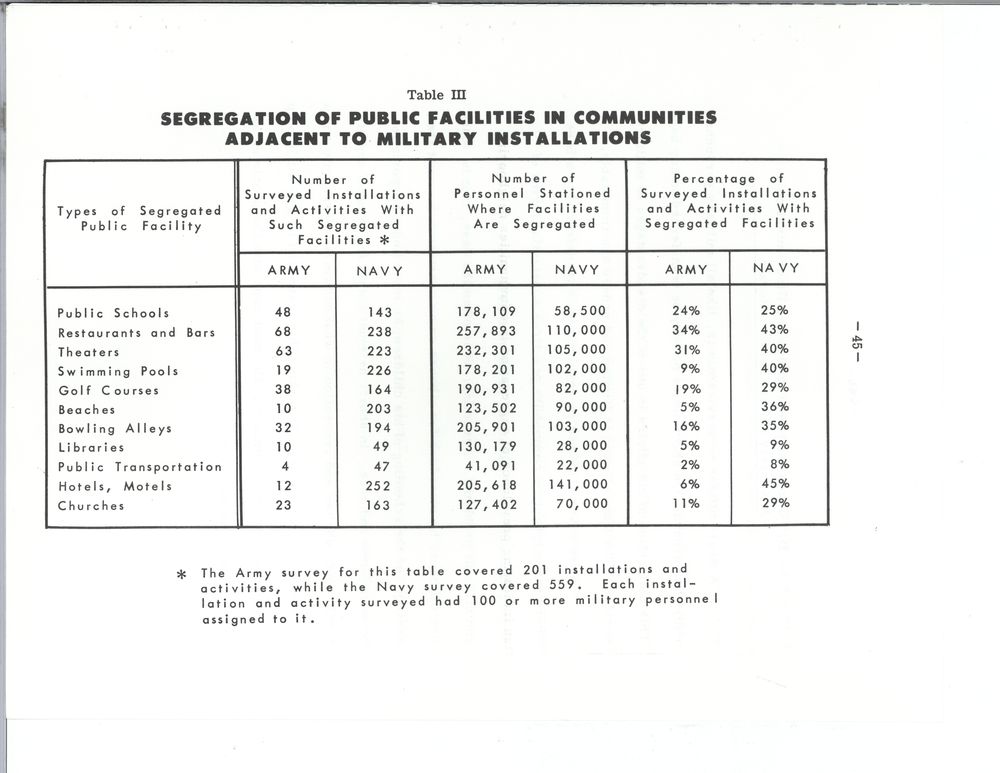

“Usually the Negro officer or serviceman has few friends in the community where he is sent. He and his family must build a new life, but many doors are closed outside the Negro section of town. Drug stores, restaurants and bars may refuse to serve him. Bowling alleys, golf courses, theatres, hotels and sections of department stores may exclude him. Transportation may be segregated. Churches may deny him admission. Throughout his period of service at the particular base he is in many ways set apart and denied the general freedom of the community available to his white counterpart.

…To all Negroes these community conditions are a constant affront and a constant reminder that the society they are prepared to defend is a society that deprecates their right to full participation as citizens.

This should not be.”

Equality of Treatment and Opportunity for Negro Military Personnel Stationed within the United States: Initial Report, page 48.

The Gesell report also highlighted specific examples of the military’s role in discrimination, including:

- Large disparities in statistics between Black enlisted members and Black officers; for example, 5% of Air Force enlisted personnel in 1962 were Black, while 0.2% of its officers were Black

- No mechanism for service members to submit formal complaints about racism on bases or for local leadership to track and address these complaints

- Commanders arranging official activities in partnership with segregated organizations and denying opportunities for Black service members; for example, removing Black musicians so military bands could perform at segregated events

- Racist policies in communities near military bases, including rules that barred Black personnel from renting or buying homes, sending their children to local public schools, riding local buses and taxis, and visiting local libraries, churches, beaches, bars, and restaurants – with 34% of Army bases and 43% of Navy bases located in communities with segregated restaurants.

The Committee gave recommendations on ending these injustices, from suggesting that the Defense Department create guidelines on handling civil rights complaints, to barring all service members from visiting any segregated business. They suggested forming committees at each military installation to work with local communities on establishing inclusive policies; requiring commanders to help Black service members get their children into local schools; and even – in what a Defense Department official called “unquestionably the most controversial” suggestion – closing bases in communities that refused to integrate.

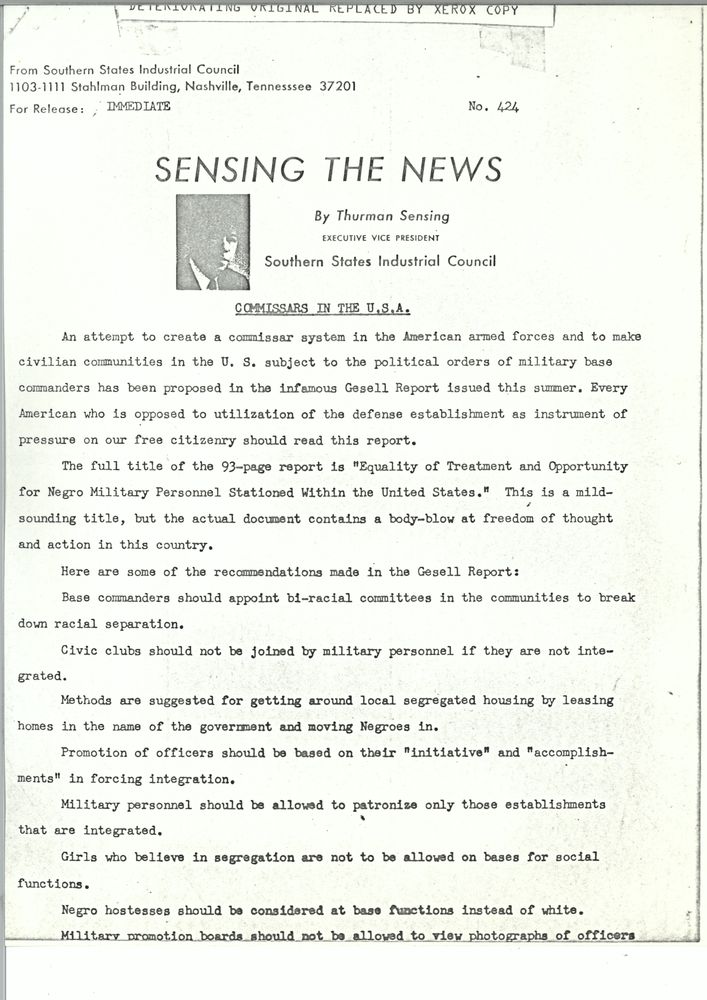

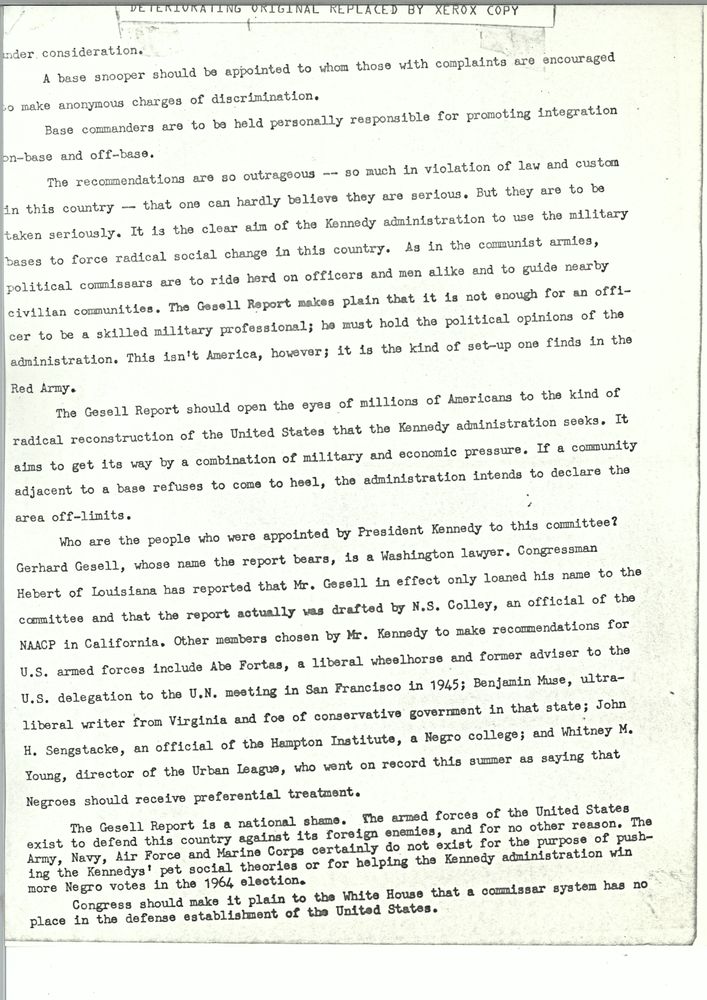

Reaction to the Committee’s initial report was swift, and Gesell heard heavy criticism from politicians, reporters, and even a friend who wrote to tell him “it is shocking that you could lend your name to a document recommending the use of our armed forces for political purposes.” In an August 1963 House of Representatives session, several segregationist politicians discussed the initial report, often focusing on the racial identities and professional backgrounds of the Committee members and describing their fears about the Committee’s recommendations:

- “Three of the members of this Committee are Negroes and the other four are in some way connected with the ADA [Americans for Democratic Action] or the ADL [Anti-Defamation League] or the NAACP. …How could we expect this report to be objective?” -Representative George W. Andrews (GA)

- “You would, by carrying out the recommendations of this Committee, be doing something that even Hitler never dared to do in his heyday.” -Representative George Grant (AL)

- The report is “one of the most dangerous and sinister threats to the freedom of this country in all our history. It will cause confusion and disrespect for the uniform.” -Representative William Jennings Bryan Dorn (SC)

One op-ed, read into the Congressional record by the segregationist Senator Strom Thurmond (SC), specifically attacked the Kennedy Administration for the report, declaring “The Gesell Report should open the eyes of millions of Americans to the kind of radical reconstruction of the United States that the Kennedy administration seeks.”

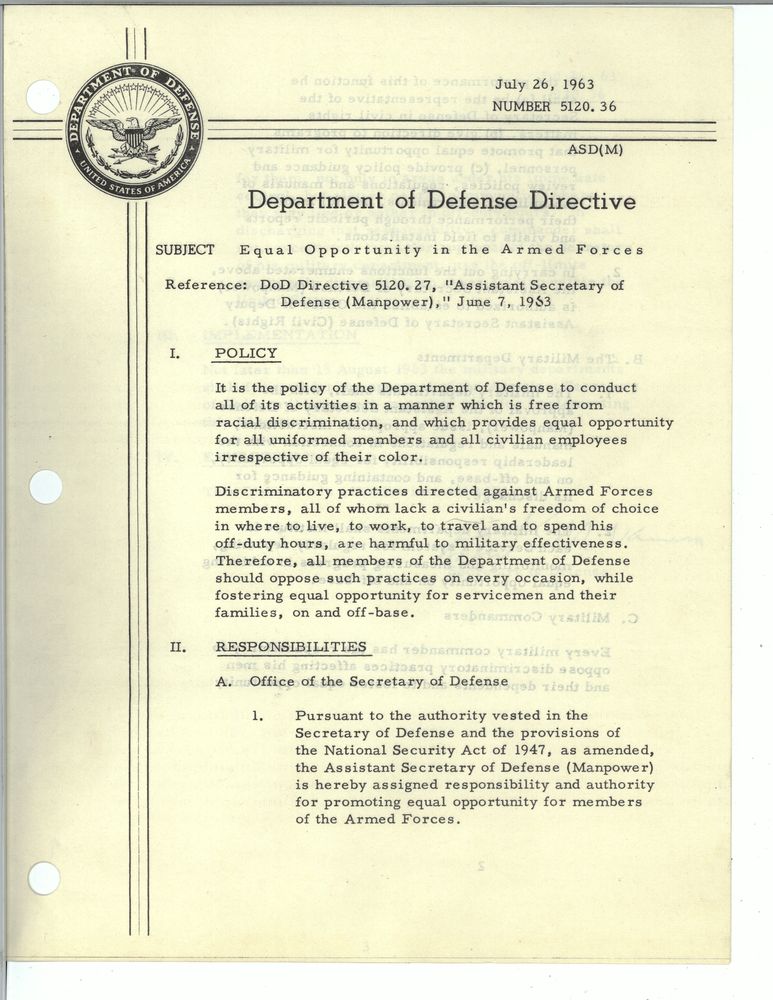

But the Administration stood by the initial report. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara noted that it highlighted “the pervasiveness of off-base discrimination against Negro servicemen and their families, the divisive and demoralizing impact of that discrimination, and the general absence of affirmative, effective action.” So, on the fifteenth anniversary of President Truman’s military integration order, McNamara issued a directive ordering military personnel to oppose discriminatory practices “at every occasion, while fostering equal opportunity for servicemen and their families, on and off-base,” and directing each branch to submit a plan for implementing the new policy.

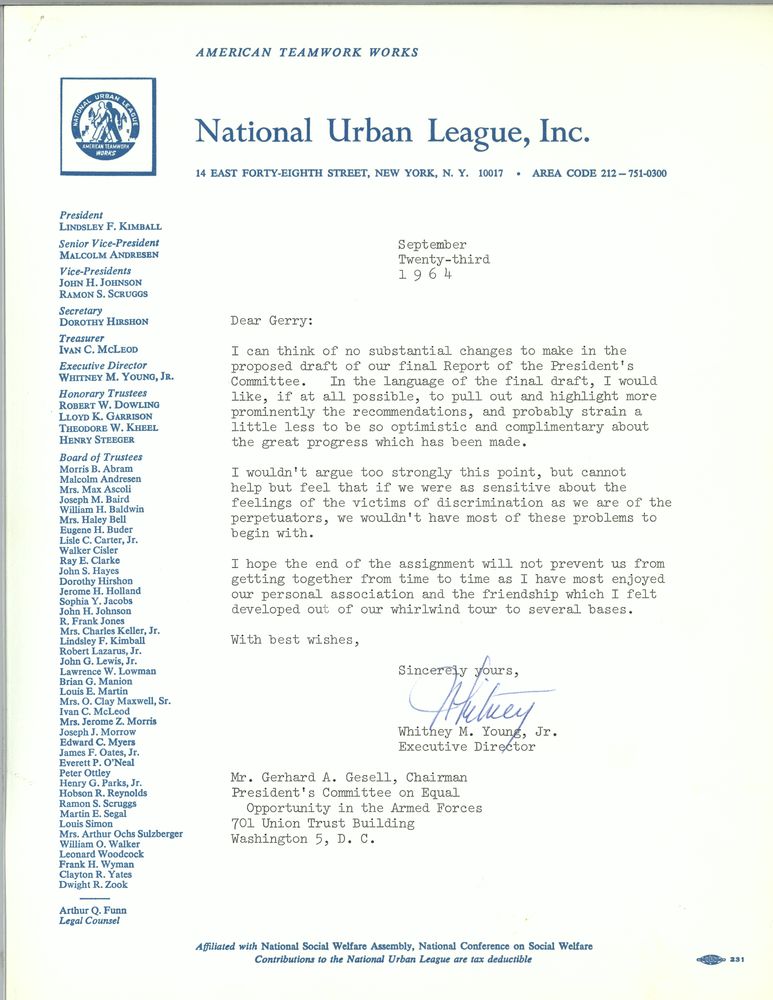

Gesell’s papers also hold drafts of the Committee’s final report, released in 1964. Committee members sent Gesell their revisions for the report drafts, and Black members particularly emphasized the importance of the report’s language and overall tone. John Sengstacke suggested the removal of a line that implied “there is no segregation” in overseas bases, while Whitney Young, Jr. advocated for making the report less “optimistic and complimentary about the great progress that has been made,” noting: “If we were as sensitive about the feelings of the victims of discrimination as we are of the perpetrators, we wouldn’t have most of these problems to begin with.”

In its response to the Committee’s report, the Defense Department did not recommend implementing all of the suggestions – but many eventually became directives and policies of their own. In November 1963, commanding officers were barred from allowing the military’s participation in segregated events, and in September 1967, the Defense Department declared segregated housing units near military bases “off limits” for all service members.

Researchers are welcome to explore more documents related to the work of the President’s Committee on Equal Opportunity in the Armed Forces by clicking on any of the linked folder titles in both of these newly-digitized collections:

*Content note: The JFK Library’s archival collections on minoritized communities, including Black communities, often contain racist, derogatory, and/or outdated language to refer to these communities; some links in this post lead to archival materials that may contain such language. The original items and language are preserved to facilitate access to the full historical record; see our note on the work we’re doing to alert users to such materials.

It is a great experience to read all this stuff. thank you.