By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

In 1948, 33-year-old Herbert E. Tucker, Jr. was a new lawyer and a rising leader in Boston’s NAACP branch when he first crossed paths with a young Congressman who made an impression: John F. Kennedy. Over the next few years, as Tucker grew his activism and his law practice (the first Black-owned law firm in Boston), he also deepened his understanding of the Boston Black community’s needs — and his connections to the city’s best-known Black organizers, journalists, and politicians.

So when John F. Kennedy’s 1952 Senate campaign team needed help understanding issues that mattered to Massachusetts’s Black voters, they reached out to Tucker. He joined up again for both Kennedy’s 1958 Senate campaign and 1960 Presidential campaign, conducting voter outreach and building pro-Kennedy coalitions in Black communities across the country. In 2008, Tucker’s family donated his papers to the JFK Library archives, giving researchers a glimpse into his work and its impact on the 1958 and 1960 elections. We’ve recently finished digitizing and cataloging Tucker’s papers for free online access, and we’re excited to share them with you!

The year Tucker and Kennedy met, Black voters chose the Democratic Presidential candidate, Harry Truman, at an overwhelming 78%. But with widespread racial discrimination, segregation, and violence – and no major political party united in fighting the policies behind these injustices — Black voters weren’t necessarily a unified voting bloc. By 1952, roughly half of Black Americans identified as Democrats, and Black community leaders like Herbert Tucker felt many politicians, including John F. Kennedy, weren’t prepared to earn their votes.

In his 1967 oral history with the JFK Library, Tucker remembered Kennedy’s early relationship with Black communities in Massachusetts: “It was a matter of…distrust. …Mainly because he had had no contact, had made no effort to have any contact with Negroes and seemed to be impervious to the problems.” But, Tucker said, “There were just a few of us who had faith in him…that once he became familiar with the problem, that we were sure that something could be done about it.” Tucker recalled advising the 1952 Senate campaign, introducing Kennedy to Black civic leaders and organizations, and even paying for Kennedy’s NAACP membership (“He still,” Tucker laughed, “owes me two dollars.”).

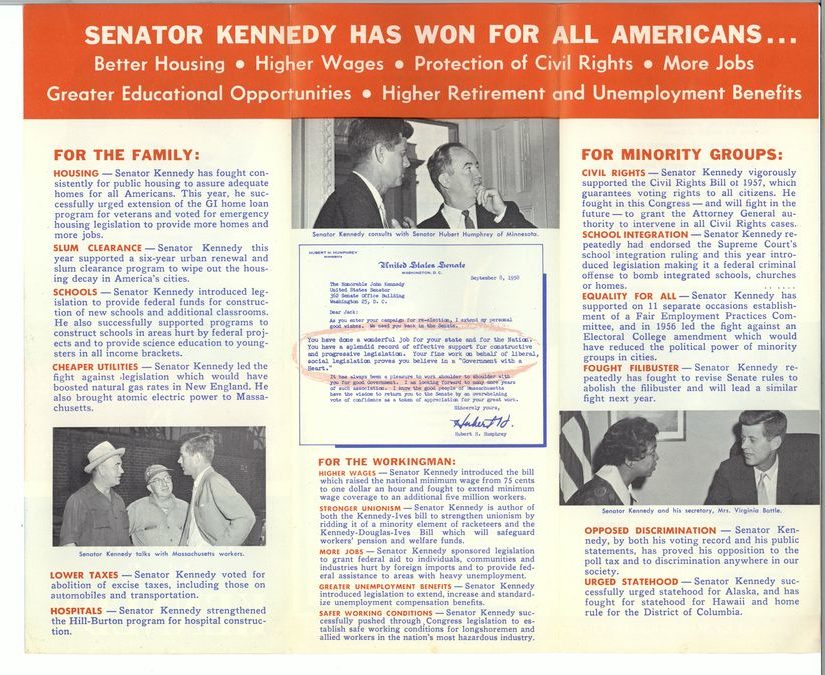

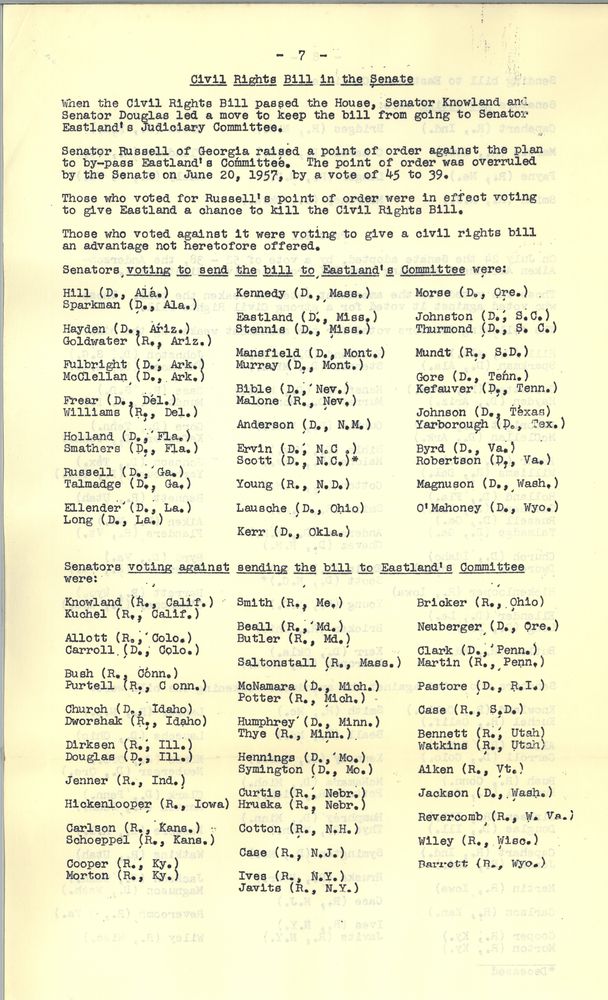

Kennedy won his election, but Tucker noted that “most liberals were very cautious as to how far they were going to take a stand on some of these [civil rights] problems, and he followed into that pattern.” It wasn’t long before Kennedy voted with Southern Democrats, including staunch segregationists, on two key issues during the Senate’s debate over the 1957 Civil Rights Act – elements that the NAACP publicly slammed as attempts “to kill the Civil Rights Bill.”

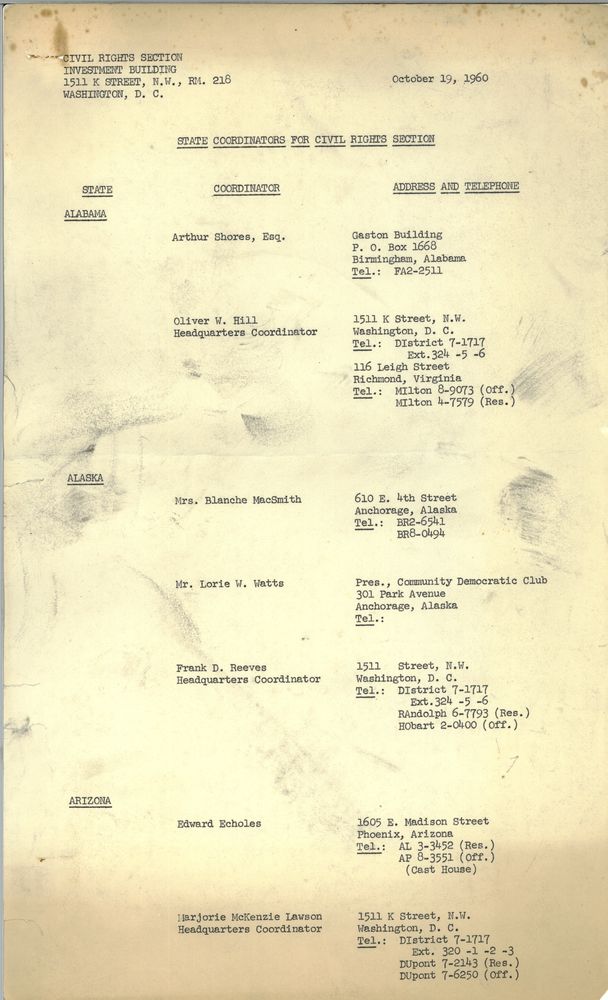

Tucker recalled being “very critical” of Kennedy’s votes at the time, but “cautiously accepted” the Senator’s rules-based explanation of his votes. When he joined the 1958 campaign, Tucker focused on bringing the Senator to Black spaces (including the famed Freedom House in Roxbury) and leveraging his own connections to boost support for Kennedy among his influential friends and colleagues. Tucker formed and led the Massachusetts Citizens’ Committee for Minority Rights, and his personal invitation to help plan one of the group’s campaign events went out to some of Boston’s best-known Black citizens, including:

- Royal Bolling, who would become a state Representative and sponsor the legislation that led to Boston’s school desegregation;

- Dexter Eure, pioneering Boston Globe journalist;

- Lincoln Pope, the first Black Democrat elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives;

- Paul Parks, a civil engineer who would be the state’s first Black Secretary of Education;

- Frank W. Morris, an artist and the first Black director of any Massachusetts state agency;

- Silas “Shag” Taylor and Balcom “Bal” Taylor, brothers who owned both the Lincoln Pharmacy and the Pioneer Club, a famed Boston jazz club that doubled as a meeting place for local Black leaders;

- Edward O. Gourdin, an Olympic silver medalist who was both the first person in history to hit a 25-foot long jump, and the first African American and the first Native American (Seminole) Superior Court judge in any New England state.

![Hon. Edward O. Goudin [sic]

80 presidents Lane Quincy Massachusetts September 5 1958

Dear Judge:

As a member of the Kennedy for Senator campaign finance committee I have been asked to call together a small select group of outstanding men friends of Senator Kennedy - to meet at my home 93 Hutchings Street, Roxbury on Wednesday evening September 10th 1958 at 8:00 to develop plans for a dinner at which the Senator will be guest of honor, and senator Paul Douglas of Illinois will be the Principal speaker, addressing himself to the subject of civil rights.

Teddy Kennedy and Steve smith, brother and brother-in-law respectively of the senator, will be on hand to assist us in working out the details.

if you cannot make it, will you please call me.

Sincerely,

Herbert E Tucker, Jr](https://jfk.blogs.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2023/01/HTPP-001-002-p0038.jpg)

Tucker also helped conceptualize a version of the popular “Kennedy teas” that the campaign would call the “Kennedy Tea for Negro Women,” targeting women voters in Black communities. As Chair of the Tea, Tucker helped set up a committee of roughly fifty prominent Boston-area women to serve as hostesses, coordinate logistics, and send invitations to ten of their friends, who would, in turn, each invite their friends. Often including a short speech by Kennedy and a meet-and-greet reception line, campaign teas were a key strategy for quickly reaching up to thousands of voters in a given community – and for shining a spotlight on the pro-Kennedy views of the community leaders who served as hostesses.

Kennedy won his 1958 election with 73.5% of the vote, and, as historian Mark Stern noted, “he won most of the Black wards by an even larger margin.” Just over a year later, he announced his run for the Presidency. By this time, Tucker was Assistant Attorney General for Massachusetts, and “got a call out of the clear blue sky” from campaign staff asking him to represent Kennedy at the upcoming Democratic state convention in Michigan. In his oral history, Tucker recalled:

I found out that actually I was to be exhibit one: “Here is a Negro who has known Mr. Kennedy for a number of years and can tell you just what type of individual he was.” And I can see now, as I look back, why that was so important, because as I looked around…about thirty percent of the delegates were Negroes.

Returning from his whirlwind Michigan trip in May 1960, Tucker reported back to the campaign: “I had two impressions to overcome: 1) Senator’s failure to take a forthright stand on civil rights despite his excellent voting record. 2) The nebulous association with Governor Patterson of Alabama,” a notorious segregationist who’d announced his support for Kennedy’s Presidential bid after Kennedy hosted him for breakfast at his home. To push back on these impressions, Tucker suggested that the campaign send representatives to other conferences and follow up with various Black politicians, journalists, and civic leaders.

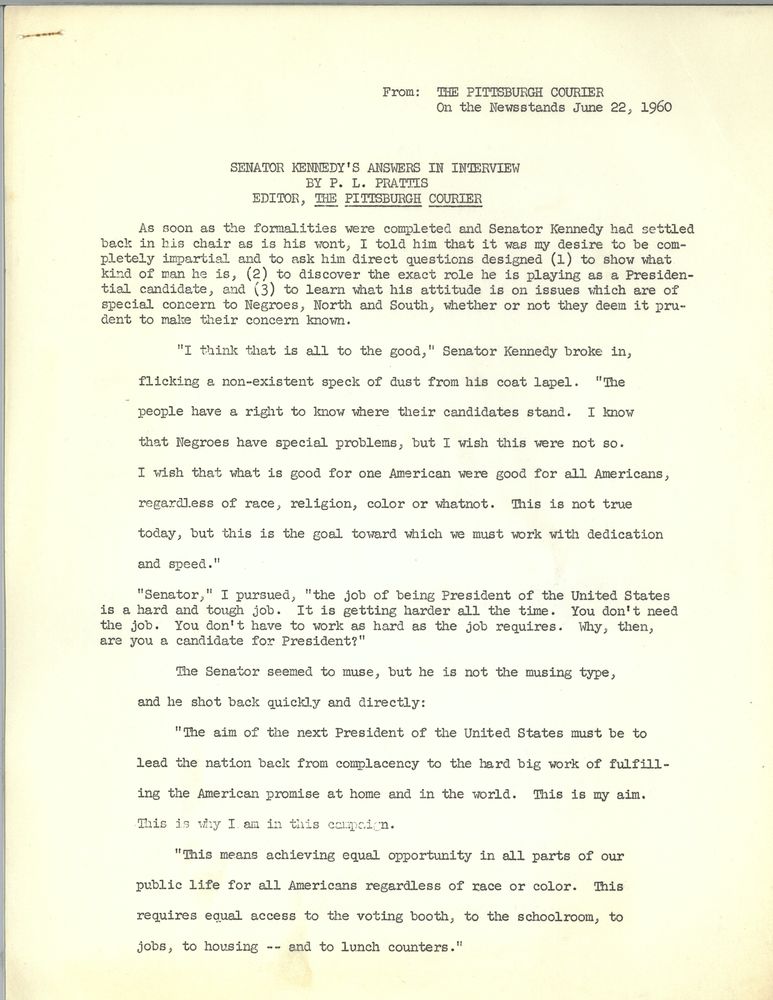

Soon after Tucker’s report, Kennedy met with a group of delegates from the Michigan convention and sat for an interview with P.L. Prattis of the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the leading Black newspapers in the country, to discuss his views on civil rights.

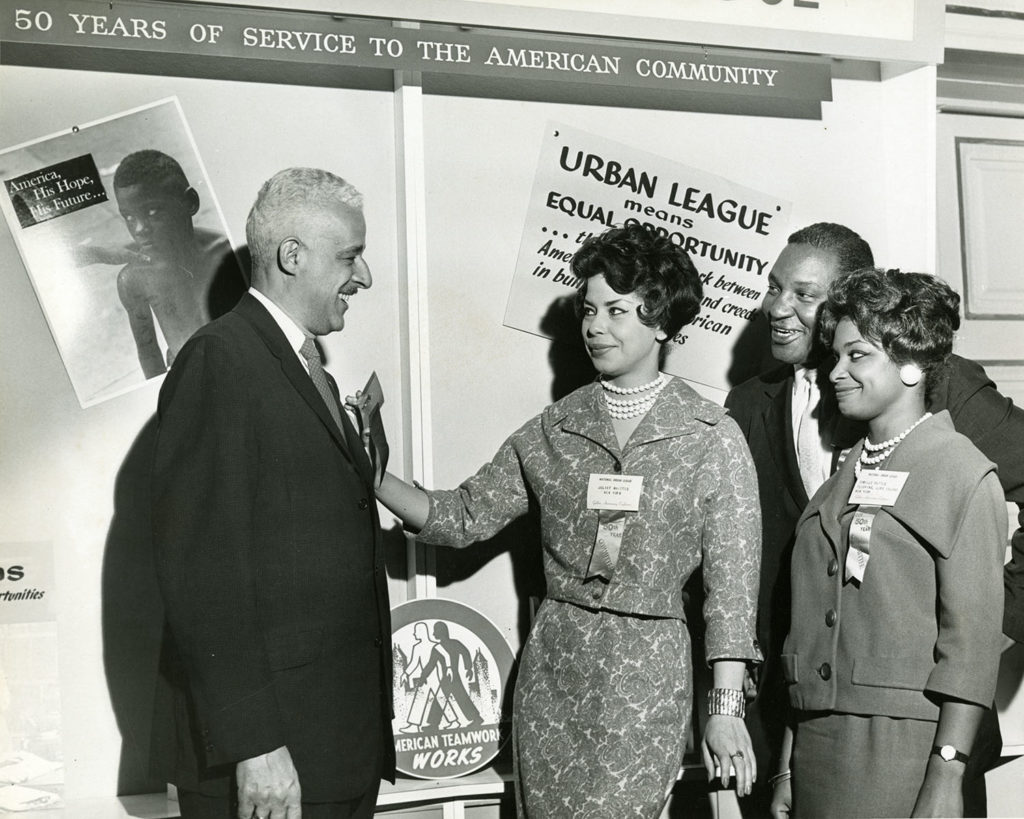

Tucker became Assistant Director of the Civil Rights Section of Kennedy’s campaign, and along with the Division’s Director, Marjorie McKenzie Lawson, focused on winning support from Black delegates at state conventions and civil rights conferences — often by attending as representatives of the Senator. Tucker advised the campaign that “in almost every instance, delegates to any convention are vehicles through which many people of a particular locality can be reached and are usually the ones who are a great factor in formation of opinions.”

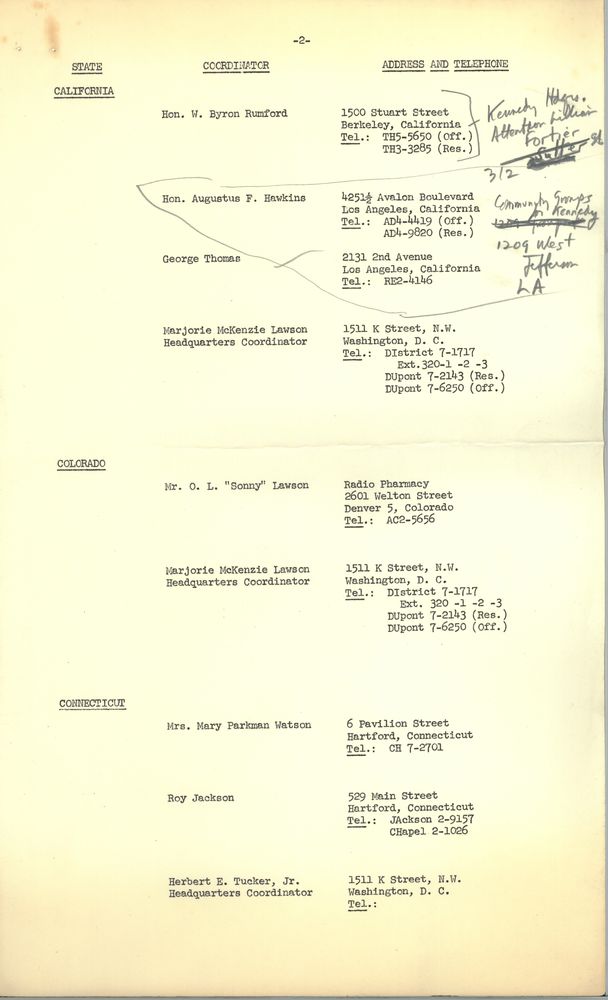

Tucker’s records also document Tucker and Lawson’s work on developing strategies for appealing to Black delegates at the Democratic National Convention in July 1960; advising the campaign on Black organizations Kennedy should speak to; and conducting outreach in crucial states with appointed Civil Rights Section State Coordinators — typically, Black civic leaders who were hugely influential in their local communities, including politician Augustus Hawkins in California; businessmen Sonny Lawson in Colorado and Hobart Taylor in Texas; and NAACP leader Ruth Batson in Massachusetts.

As election day drew nearer, the campaign won Kennedy endorsements from key people, newspapers, and organizations, including the Trade Union Leadership Council in August and civil rights leader Roy Wilkins in early October. And on October 26, 1960, campaign staffer Harris Wofford persuaded John F. Kennedy to call Coretta Scott King after her husband, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was arrested in Atlanta, Georgia; a second call by Robert F. Kennedy helped secure King’s release. With just two weeks to go before the election, the campaign quickly publicized the calls with press releases and pamphlets targeted to Black communities, and Tucker noted that Wofford “probably gave [Kennedy] the most vital piece of good advice during the campaign when he had him call Martin Luther King.”

![American Justice on Trial

Mrs. Martin Luther King: It certainly made me feel good that he called me personally and let me know how he felt. Senator Kennedy said he was very much concerned about both of us. He said this must be hard on me. He wanted me to know he was thinking about us and he would do all he could to help. I told him I appreciated it and hoped he would help. I had the feeling that if he was that much concerned he would do what he could so that Mr. King would be let out of jail. I have heard nothing from the Vice President or anyone on his staff. Mr. Nixon has been very quiet.

Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr.: I had expected to vote against Senator Kennedy because of his religion. But now he can be my President, Catholic or whatever he is. It took courage to call my daughter in law at a time like this. He has the moral courage to stand up for what he knows is right. He has shown his sympathy and concern and his respect for the Constitutional rights of all Americans. I’ve got all my votes and I’ve got a suitcase and I’m going to take them up there and dump them in his lap.

Rev. Ralph Abernathy, President, Montgomery Improvement Association; Secretary-Treasurer, Southern Christian Leadership Conference: I earnestly and sincerely feel that it is time for all of us to take off our Nixon buttons. I wish to make it crystal clear that I am not hog-tied to any party. My first concern is for the 350-year old struggle of our people. Now I have made up my mind to vote for Senator Kennedy because I am convinced he is concerned about our struggle. Senator Kennedy did something wonderful when he personally called Mrs. Coretta King and helped free Dr. Martin Luther King. This was the kind of act I was waiting for. It was not just Dr. King on trial - America was on trial. Mr. Nixon could have helped, but he took no step in this direction. It is my understanding that he refused even to comment on the case. I learned a long time ago that one kindness deserves another. Since Mr. Nixon has been silent through all this, I am going to return his silence when I go into the voting booth. Senator Kennedy showed his great concern for humanity when he acted first without counting the cost. He risked his political welfare in the South. We must offset whatever loss he may sustain. He has my wholehearted support because [end of page]

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: I am deeply indebted to Senator Kennedy who served as a great force in making my release possible. It took a lot of courage for Senator Kennedy to do this, especially in Georgia. For him to be that courageous shows that he is really acting upon principle and not expediency. He did it because of his great concern and his humanitarian bent. I hold Senator Kennedy in very high esteem. I am Convinced he will seek to exercise the power of his office to fully implement the civil rights plank of his party’s platform. I never intend to be a religious bigot. I never intend to reject a man running for President of the United States just because he is a Catholic. Religious bigotry is as immoral, un-democratic, un-American and un-Christian as racial bigotry.](http://jfk.blogs.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2023/01/JFKWHSFHW-002-012-p0016-e1674150255450.jpg)

That November, Kennedy won the 1960 Presidential election with 68% of Black voters’ support — an improvement on the 1956 Democratic ticket’s showing of 61%, but still lower than 1952 levels, when 79% of Black voters had turned out for the Democrat. While some campaign veterans and historians have attributed Kennedy’s winning 1960 margins with Black voters primarily to his last-minute call to Coretta Scott King, others disagree. Historian James Meriwether argues that “the focus on the phone calls marginalizes Kennedy’s efforts throughout the campaign to use other appeals…to secure the black vote without alienating the white southern vote,” and that the emphasis on the calls “has obscured those campaign efforts and reduced the complexity of African American voting to an oversimplified equation: Kennedy called about King, so he won the black vote.”

Marjorie McKenzie Lawson made similar statements as far back as 1965, in her oral history interview for the JFK Library. Lawson, who had recently become the first Black woman judge in the District of Columbia, argued that her and her staff’s work with Black leaders and organizations was already being erased by the narrative crediting Black vote tallies to the King phone calls:

Were we to say that Negroes were so childlike and so unsophisticated that they cared nothing for the organizational work that had been done and the recognition that they had received but had responded to one telephone call and had rushed then to the polls and voted for Senator Kennedy? I thought it was ridiculous; it was a great disservice to the people who had worked so hard in the campaign both nationally and locally. All of these interpretations…did a lot of harm to the sophistication and maturity of Negro organizations or those interracial political organizations which we had been able to develop in many communities and states.

Lawson’s statement highlights the critical role of archival collections like Herbert Tucker’s, which document the work of people who influenced the course of history, but aren’t always included in its retelling. At the JFK Library, we’re privileged to care for these materials and make them freely and widely available. You can browse the Herbert Tucker Personal Papers and read through oral histories from Tucker, Lawson, and other Black workers in and around JFK’s campaigns at the links below:

- Herbert Tucker Personal Papers

- Herbert Tucker Oral History Interview: JFK #1, 9 March 1967

- Marjorie McKenzie Lawson: Director, Civil Rights Division, Presidential Campaign

- Ruth Batson: 1952 Senate campaign staff member; President, NAACP New England

- Belford Lawson: advisor to both Senate and Presidential campaigns

- Louis Martin: Deputy Chairman, Democratic National Committee; consultant for Presidential campaign

- Frank Reeves: Presidential campaign staff member

- George Taylor: JFK’s personal chauffer and valet, 1936-1946

NOTES

* Many of the people photographed at campaign events, especially in Black communities and other communities of color, remain unidentified or partially-identified in our collections. Archivists are actively working on identifying these individuals so that their presence is known in the historical record. If you recognize any unidentified people in these photographs, please reach out to us at Kennedy.Library@nara.gov.

** The JFK Library’s archival collections on minoritized communities, including Black communities, often contain racist, derogatory, and/or outdated language to refer to these communities; some links in this post lead to archival materials that may contain such language. The original items and language are preserved to facilitate access to the full historical record; see our note on the work we’re doing to alert users to such materials.