(This post is adapted from a post published on our previous blog on 1/11/2014.)

By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed an Executive Order that changed the course of American history – and not just in the way the government planned. E.O. 10450 made “dishonest, immoral, or notoriously disgraceful conduct” – including so-called “sexual perversion” – grounds for firing any federal government employee. The order opened the door for agencies and the military to find, fire, and even publicly out suspected “homosexuals” in what’s now called the Lavender Scare.

Thousands had lost their jobs under E.O. 10450 by 1957, when Franklin E. Kameny, a young veteran with a new PhD in astronomy, started his dream job as an astronomer with the U.S. Army Map Service. But just a few months in, the U.S. Civil Service Commission started to suspect that Kameny might be gay. Investigators asked him about his relationships with men, but Kameny wouldn’t answer, explaining that “these were matters of his own personal life…having no relation to his performance in the position for which he was hired.” The Army disagreed and fired Kameny in 1958 for “immoral conduct.”

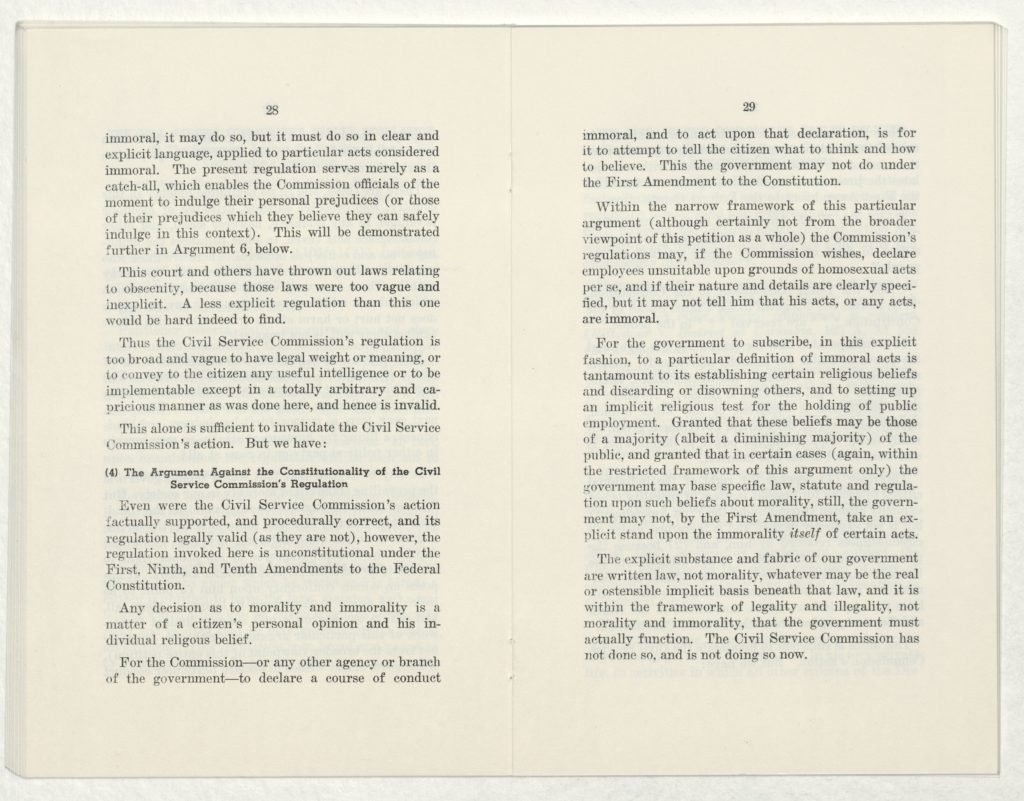

He quickly appealed to federal courts and lost twice, but when his case reached the Supreme Court in 1960, Kameny decided to try something groundbreaking: instead of denying he was gay (as fired workers often did), he’d argue that the government had no business declaring homosexuality as immoral. The Court wouldn’t review his claim (accessible in full in the National Archives Catalog), but Kameny had already made history; his was the Supreme Court’s first civil rights claim based on sexual orientation.

Being fired under E.O. 10450 – and fighting back in court – shifted Kameny’s entire life plan; he became a full-time, lifelong activist for gay rights. Less than a year after his case was dismissed, he formed the grassroots advocacy group the Mattachine Society of Washington and set his sights on equal treatment and employment rights for gay Americans. Kameny sent letters arguing his case to officials across the entire government – including at the very top – and the John F. Kennedy administration received its first letter from Kameny a few months after the Inauguration. The letter, the first of several that are now part of our archives, was the start of his group’s effort “to stand up for their rights and freedoms.” Kameny explained:

In World War II, I willingly fought the Germans…In 1961, it has, ironically, become necessary for me to fight my own government, with words, to achieve some of the very same rights, freedoms, and liberties for which I placed my life in jeopardy in 1945.

JFKWHCNF-1418-002-p0002

Over the years, his letters to President Kennedy made varied and detailed arguments, but there was one tactic Kameny deployed most: using the President’s own ideas, and sometimes his exact words, to make the case for gay rights. His first letter to JFK referenced a famous Kennedy campaign speech, and asked for a “New Frontier” in the country’s treatment of his community. Later in the same letter, he quoted another Kennedy speech to point out the gap between political rhetoric and the lived experience of marginalized people:

You yourself said in your recent address at George Washington University ‘that (people) desire to develop their own personalities and their own potentials.’ But your government…certainly does not permit the homosexual to develop his personality and his potential.

JFKWHCNF-1418-002-p0004

“Let more than mere lip service,” he demanded, “be given to laudable-sounding ideals!”

In August 1962, Kameny sent another letter to the President, arguing that homophobic employment policies were “inexcusably and unnecessarily wasteful of trained manpower.” In this letter, Kameny argued for gay worker protections by invoking one of the most famous Kennedy phrases:

You have said ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.’ We know what we can do for our country; we wish to do it; we ask only that our country allow us to do it.

Franklin Kameny to John F. Kennedy, August 28, 1962.

Kameny also sent Mattachine Society pamphlets and reports to President Kennedy, laying out some of his other goals for the community. Some of the documents foreshadow Kameny’s famous fight to remove “homosexuality” from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (after several presentations from Kameny, the APA voted to remove the listing in 1973).

![Discrimination Against the Employment of Homosexuals

I. Introduction

A. Premises

The homosexual is one whose direction of choice of a sexual partner differs from that of the majority of the citizenry in what he is attracted to and chooses partners of his or her own sex.

Homosexuality is neither a sickness, disease, neurosis, psychosis, disorder, defect, nor other disturbance, but merely a matter of the predisposition of a significant of a significantly large minority of our citizens.

Homosexuals are a minority group, no different, as such, from others; and their problems are those of prejudice against minorities - prejudice and discrimination as unreasonable and as ill-founded as those directed against others of our minorities.

B. Statistical Background

Lest this be considered an area too small and unimportant for this committee, a very brief background survey is in order.

While estimates of the number of homosexuals vary, and (unlike the cases of the Negro, the Jew, and others) exact figures are impossible to obtain, an informed reading of the Kinsey Report, combined with intelligent observation, leads to an estimate of at least 10 per cent of the non-juvenile population of the country (both men and women).

There is a strong tendency for homosexuals to migrate from rural to urban areas, and from small urban areas to large ones. Therefore, as a reasonable figure with which to work, one may say that 10 per cent of the total population of a large metropolitan area such as Washington is homosexual.

Thus some 15,000,000 American citizens, and some 250,000 residents of the Washington area, are homosexuals. This makes the makes the homosexual community one of the largest of the national and the local minority groups.

C. General Employment Situation

The general employment situation for homosexuals can be summed up very briefly: Virtually anyone known to be a homosexual is unemployable, regardless of all other aspects of his background [end page]](https://jfk.blogs.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2021/05/JFKWHCNF-1418-002-p0017.jpg)

Homosexuality is neither a sickness, disease, neurosis, psychosis, disorder, defect, nor other disturbance, but merely a matter of the predisposition of a significantly large minority of our citizens.

JFKWHCNF-1418-002-p0017

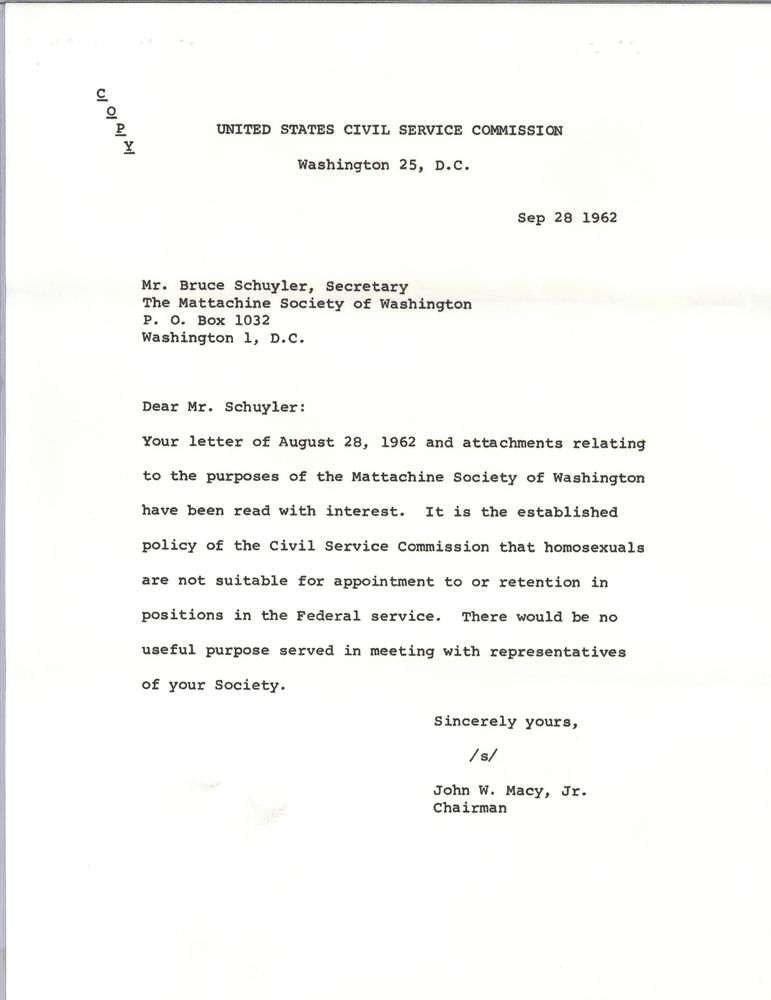

As Kameny and the Society kept sending letters to the White House throughout 1962 and 1963, they expressed frustration that the President and his team didn’t have much to say in response. In fact, the only reply we’ve found in the President’s papers is a brief note from Civil Service Commission Chair John W. Macy to Mattachine Society Secretary Bruce Schuyler, after Schuyler requested a meeting. Macy wrote:

It is the established policy of the Civil Service Commission that homosexuals are not suitable for appointment to or retention in positions in the Federal service. There would be no useful purpose served in meeting with representatives of your Society.

JFKWHCNF-1418-002-p0025

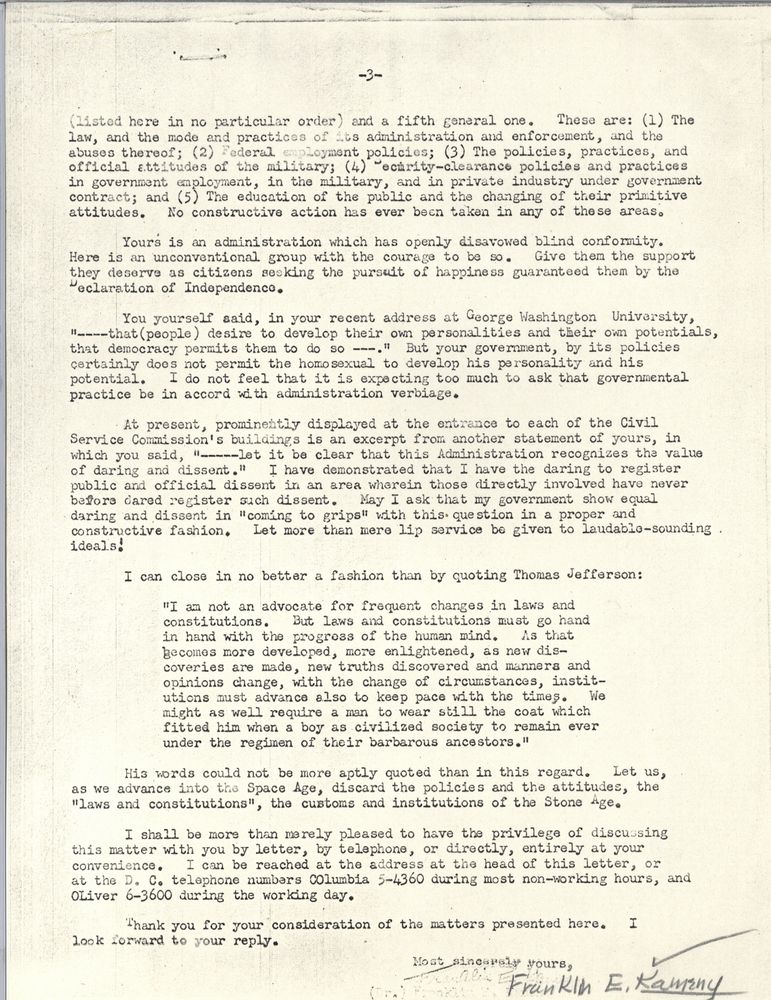

Concerned by his government’s disinterest, Kameny wrote to Ted Sorensen, Special Counsel to the President, in March 1963. Kameny noted that his group had tried to work quietly with the government to address discriminatory policies – and warned that if officials continued to dismiss them, his community would take its cue from the Black Civil Rights Movement and shift to more visible protest.

![The Mattachine Society of Washington

March 6, 1963

Mr. Theodore C. Sorensen

Special Counsel to the President

The White House

Washington DC

Dear Mr. Sorensen:

I queried you on Sunday evening, March 3, at All Soul's Unitarian Church, in regard to Federal Government discrimination against the homosexual community. I received the astounding and incredible reply that you were unaware of such discrimination.

In order to inform you of the situation, I enclose (1) A report recently presented to the DC Advisory Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity; a subcommittee of the US Commission on Civil Rights. The report is entitled: Discrimination Against the Employment of Homosexuals; (2) A copy of a letter, dated August 28, 1962 (and enclosures) sent to the President of the United States, and thus far unanswered; (3) a copy of a follow-up letter very recently sent to the President of the United States. Please note that Item (1) has appended to it a copy of a letter from the US Civil Service Commission's Chairman, John W. Macy, Jr., setting forth, bluntly and clearly, present Federal policy on these matters - a policy which differs in no way from Southern policies of exclusion of the Negro, and is not one whit more justifiable.

We are very well aware that this is a delicate question, Mr. Sorensen, with potentially explosive political implications. However, it will only become increasingly explosive if no constructive action is taken on it. We have stated, in all good faith, in our letter to the President, that we do not wish in any way to embarrass the administration or anyone in it. But we are absolutely determined that constructive action WILL be taken on this question. We WILL achieve the rights for which we are fighting, which are properly ours, and which we do not now have.

We wish to cooperate in any way possible, if the chance for friendly, constructive cooperation is offered to us by you, but if it continues to be refused us, then we will have to seek out and to use any lawful means whatever, which seem to us appropriate, in order to achieve our lawful ends, just as the Negro as done in the South when he was refused cooperation.

This is a problem which affects 15,000,000 American citizens - almost as many as there are Negroes - a group who see themselves excluded, as a matter of course, from every statement on equal opportunity for all, from denials that this country has second-class citizens, and from efforts to achieve, maintain, and protect the rights and freedoms of all citizens; and who are as rapidly losing patience with the hypocrisy involved, as has the Negro community in its struggle.

If you truly did not know about the situation before this, you now know at least a little about it. We can supply you with as much additional information as you might seek.

With the preceding established, we ask you again the question which was asked on the evening of March 3: Does the Administration plan to take any constructive action in regard to present high discriminatory Federal policies and practices in regard to homosexuals? If so, what and when? If not, why not? [end of page]](https://jfk.blogs.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2021/06/JFKWHCNF-1418-002-p0006.jpg)

…We will have to seek out and to use any lawful means whatever, which seem to us appropriate, in order to achieve our lawful ends, just as the Negro has done in the South when he was refused cooperation.

JFKWHCNF-1418-002-p0006

The government didn’t address any of Kameny’s concerns, so in 1965, he followed through on his letter and organized the first protest for gay rights to ever take place in front of the White House. Ten years later, the Civil Service Commission ended its policy broadly banning gays and lesbians from federal service – but other restrictions, including those barring openly LGBTQ+ people from serving in the military or accessing classified information – stayed in place for several more decades. E.O. 10450 was formally repealed in its entirety on January 17, 2017.

Though Kameny passed away in 2011 without ever working as a professional astronomer again, he remained an outspoken leader in the LGBTQ+ rights movement for the rest of his life (and he even pops up again in our archives, in records related to the 1972 Presidential race). In 2009, when the U.S. government issued a formal apology to Kameny for its discrimination against him, he noted: “In a sense, it took 50 years – but I won my case.”

To learn more about Frank Kameny, the mid-20th century LGBTQ+ rights movement, and the Lavender Scare, check out these sources:

- The Kameny Papers Project

- Oral history interview of Franklin E. Kameny. Franklin E. Kameny Collection, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

- The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual vs. the United States of America, by Eric Cervini

- The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government, by David K. Johnson

- Gay Is Good: The Life and Letters of Gay Rights Pioneer Franklin Kameny, by Michael G. Long

With special thanks to Charles Francis, founder of The Kameny Papers project.

Thanks for this post, and happy Pride Month!

[…] government and military to find, fire, and out people who were suspected of being homosexual (Chandler). One of these people was Frank Kameny. Kameny was an astronomer with the U.S. Army Map Service but […]

[…] point was not lost on homosexuals at the time. In a 1961 Supreme Court appeal (which the Court declined to hear), Frank Kameny made the argument explicitly. Kameny, a […]

[…] point was not lost on homosexuals at the time. In a 1961 Supreme Court appeal (which the Court declined to hear), Frank Kameny made the argument explicitly. Kameny, a […]

[…] point was not lost on homosexuals at the time. In a 1961 Supreme Court appeal (which the Court declined to hear), Frank Kameny made the argument explicitly. Kameny, a […]

[…] Frank Kameny […]

[…] Frank Kameny […]