By Emily Mathay and Stacey Flores Chandler, Textual Archives Reference

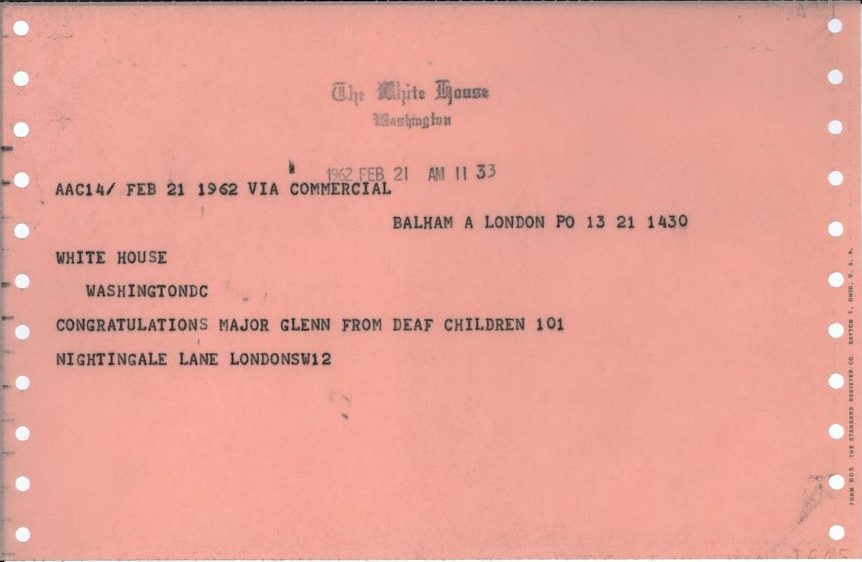

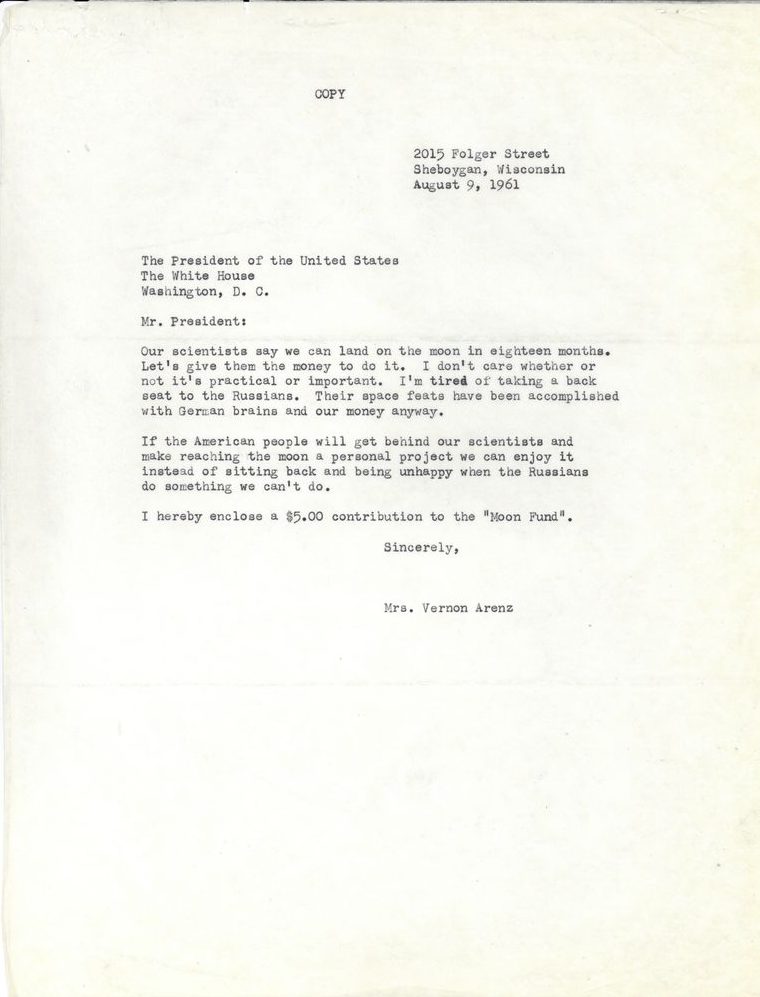

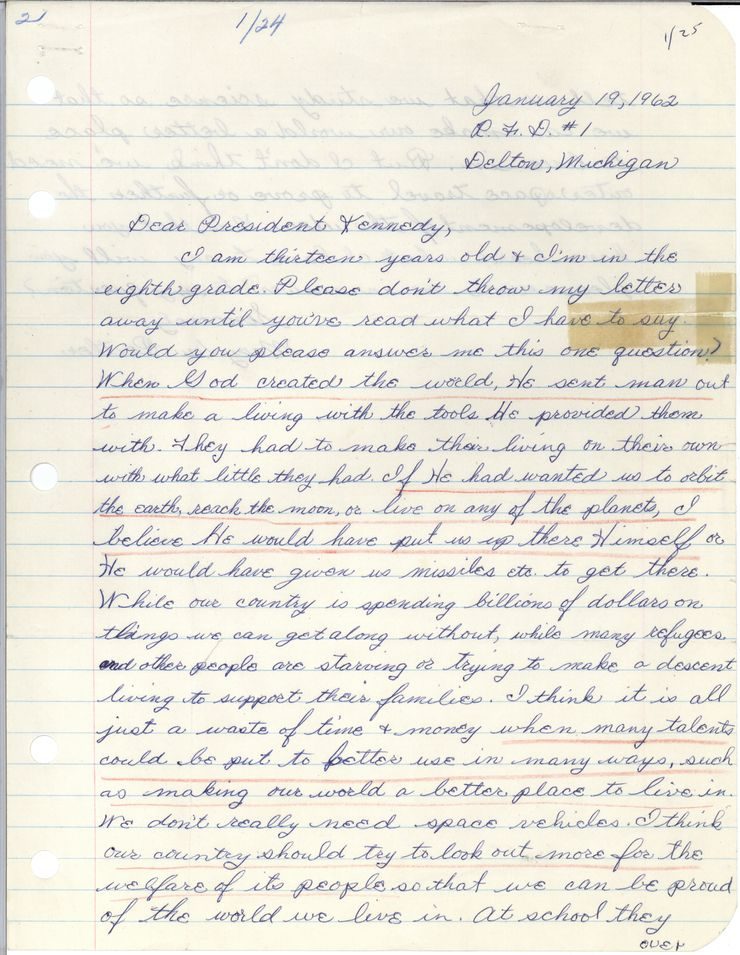

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the world’s first artificial satellite, and instantly sparked fear that the United States might be losing the Space Race. But in 1958, the U.S. government started Project Mercury, a program focused on human spaceflight that soon reached its own milestones: Commander Alan Shepard became the first American in space in 1961, and Colonel John Glenn was the first American to orbit Earth a few months later. After these famous flights, thousands wrote to President John F. Kennedy, and their letters are now in the archives here at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library (along with boxes of mail on hundreds of other topics).

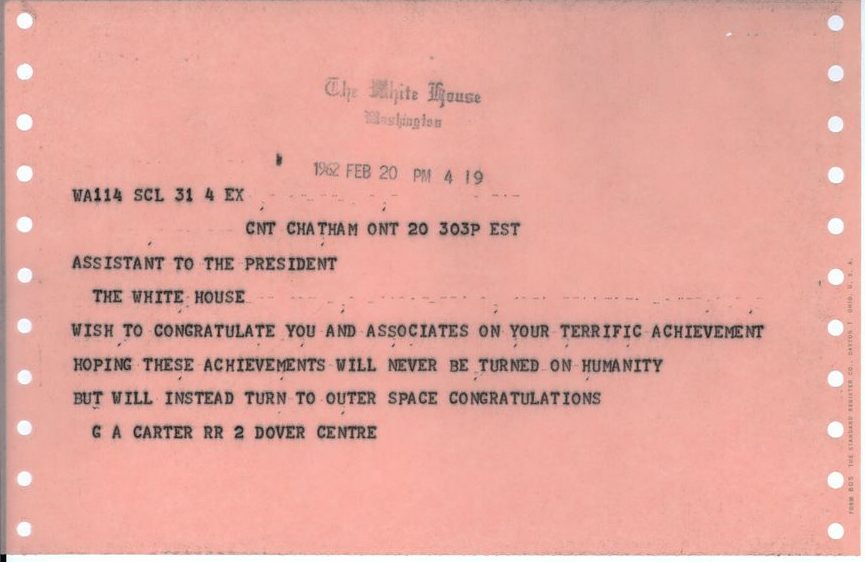

Messages from people around the world in response to the flights of astronauts Alan Shepard and John Glenn. White House Central Subject Files, “Outer Space” series, Boxes 652-655, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Their messages cover some similar themes, from praise for the astronauts and scientists, to worries about powerful new technology and the cost of these missions. But scattered throughout the boxes are letters carrying a different observation about the space program: the astronauts known as the Mercury Seven all shared the same race, religion, marital status, and gender. Pointing out the cultural impact of the space program, some argued that more American communities should be visibly represented in it – and they wrote to the President to advocate for those who seemed to be left out.

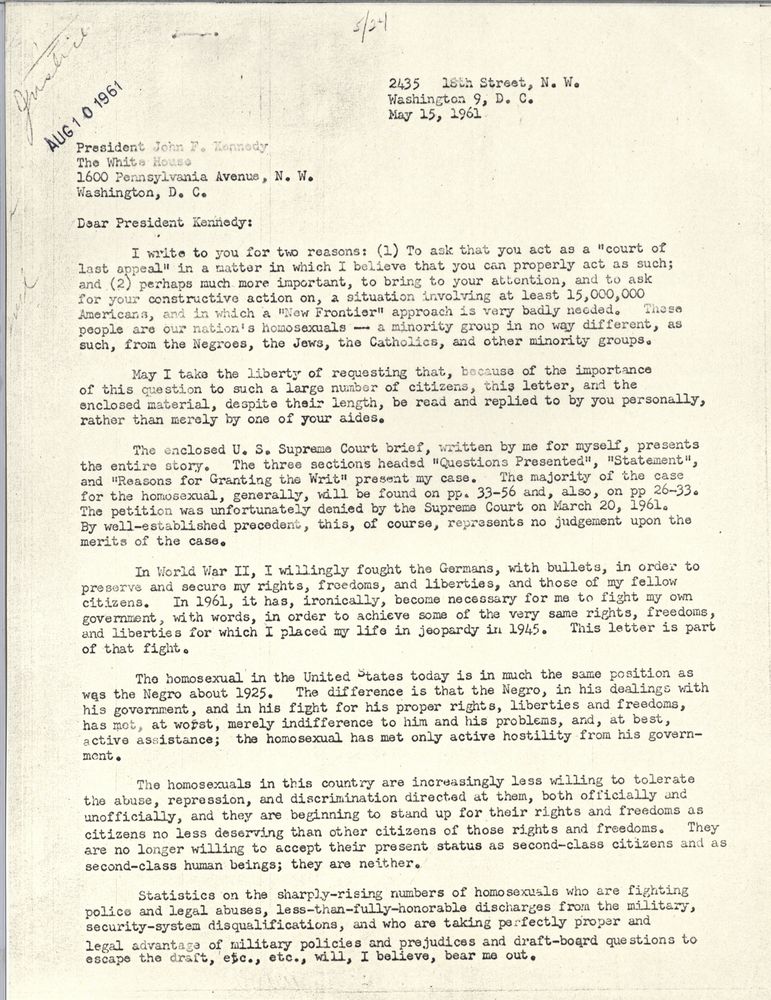

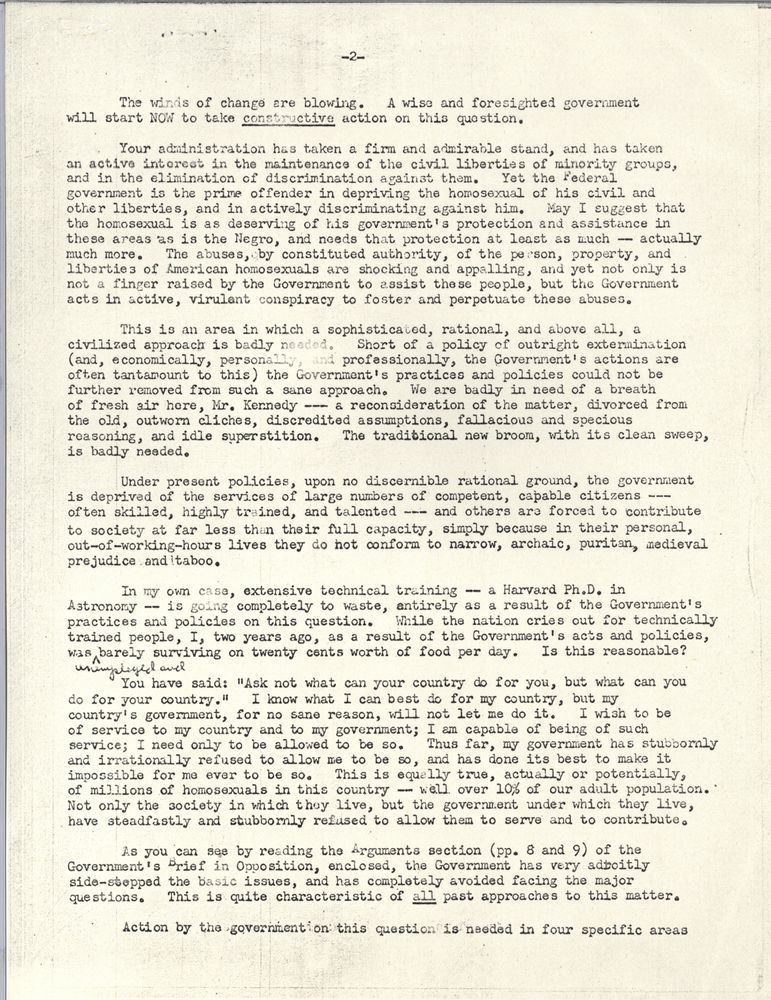

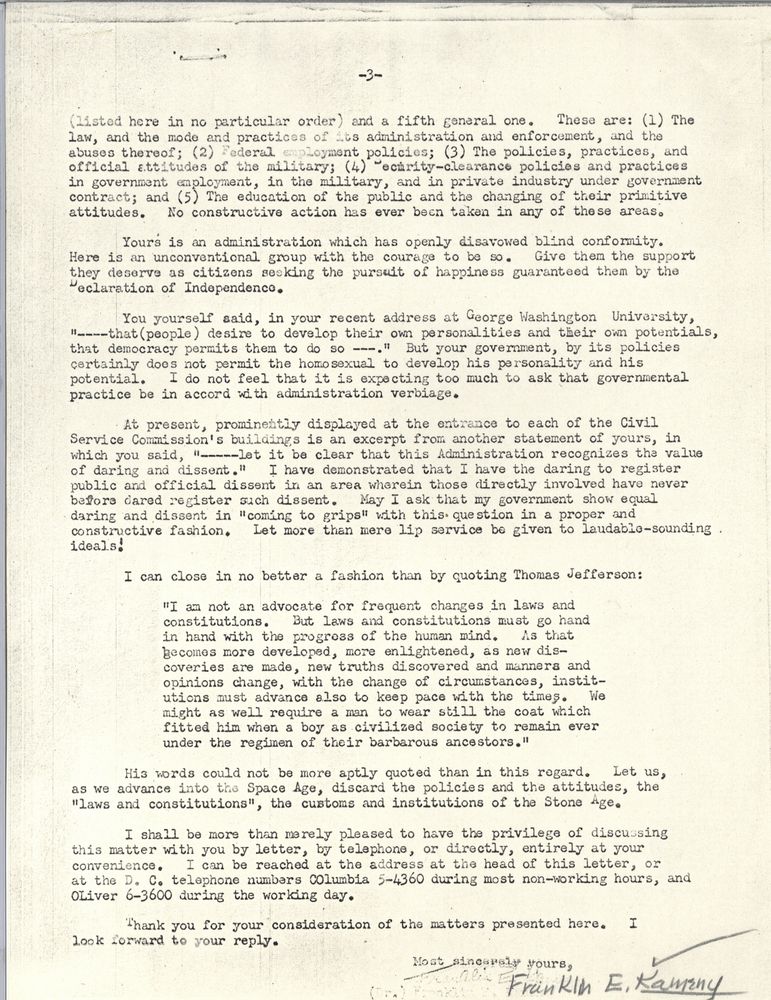

One of these writers was Dr. Frank Kameny, an astronomer who’d worked for the U.S. Army Map Service and hoped to become an astronaut. Like many civil servants in the wake of Executive Order 10450, Kameny was fired from his federal job in 1957 when his supervisors learned he was gay. His dream of contributing to the space program was ended; he would never work for the government or as a professional astronomer again. Instead, Kameny formed the Mattachine Society of Washington in 1961 and dedicated his life to fighting for LGBTQ+ rights. He wrote letters to the President evoking Kennedy’s own words to argue for his community’s right to work for the U.S. government:

In my own case, extensive technical training – a Harvard Ph.D. in Astronomy – is going completely to waste…You have said: ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.’ I know what I can best do for my country, but my country’s government, for no sane reason, will not let me do it.

JFKWHCNF-1418-002. Letter from Frank Kameny to John F. Kennedy, 15 May 1961. White House Name File, Box 1418, Kameny, Franklin E. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

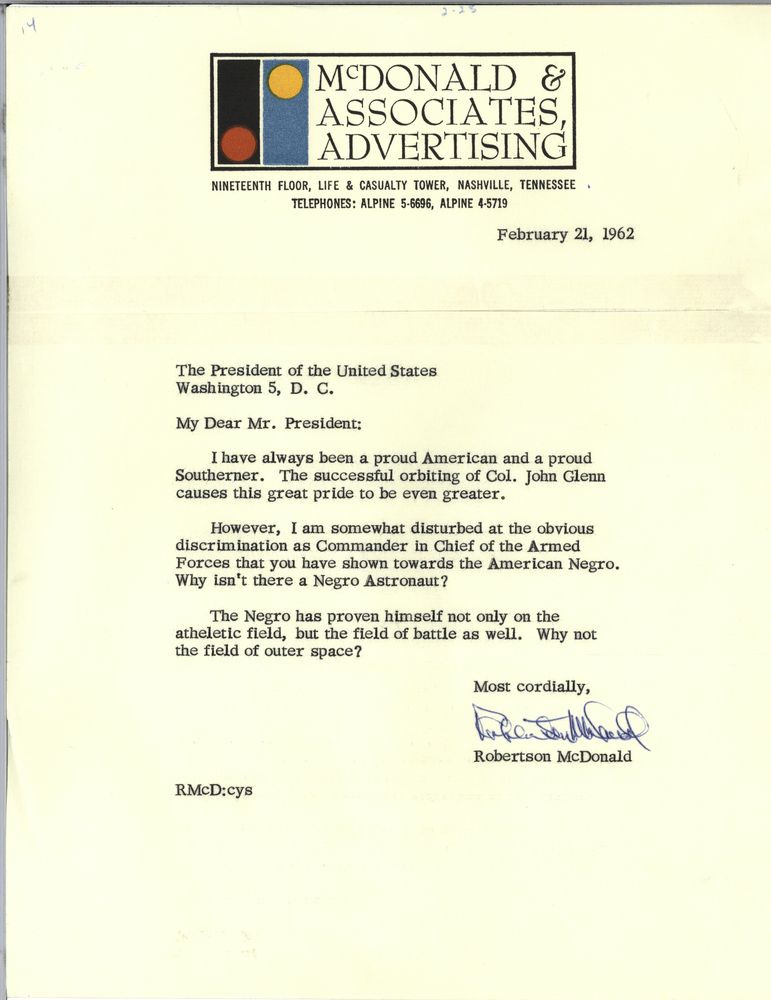

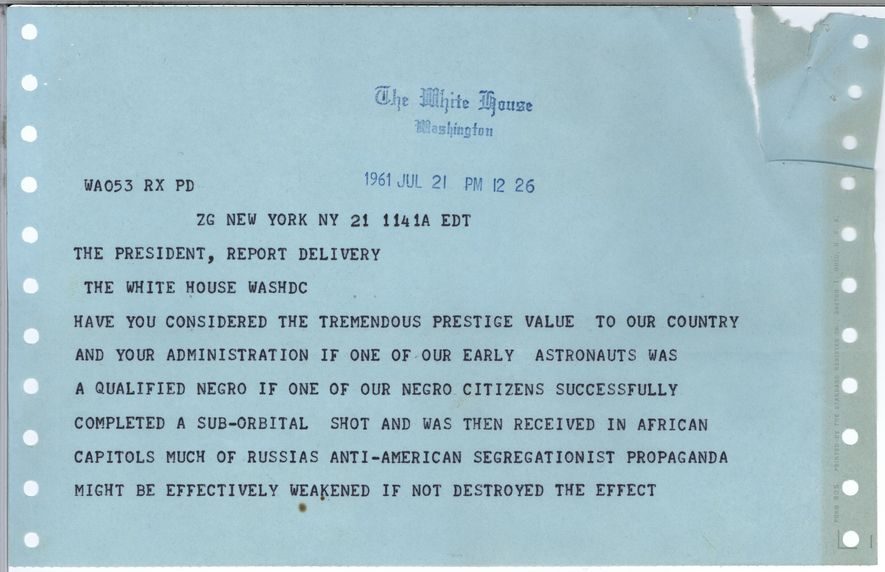

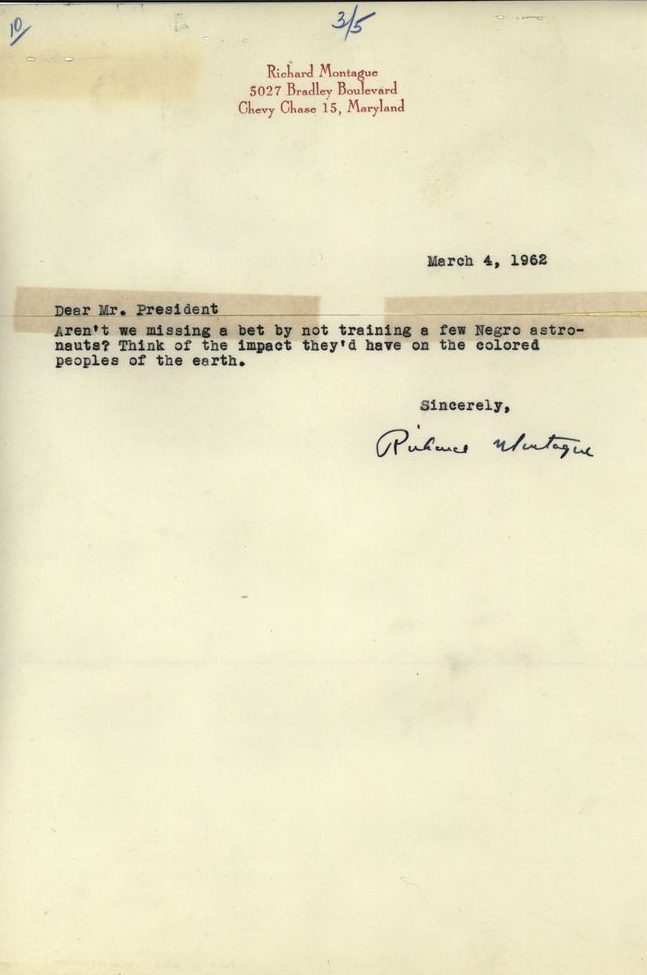

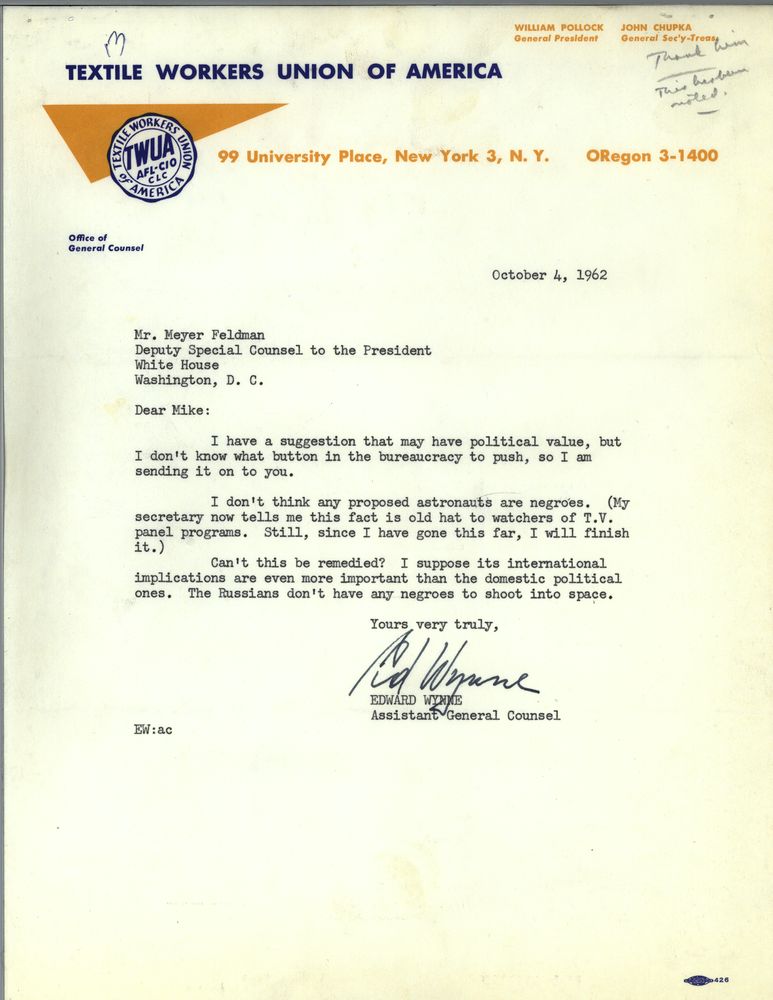

Meanwhile, as both the Space Race and the Civil Rights Movement made national headlines, letters arrived at the White House urging President Kennedy to choose the world’s first Black astronaut. Some argued that the selection would support American civil rights efforts, while others pointed out the potential boost to worldwide opinion of the U.S. Behind the scenes, the President’s aides asked the Defense Department to look into finding an African American astronaut candidate, and in 1962 the Air Force suggested a candidate for training: Captain Edward Dwight, Jr., a 27-year-old jet pilot with a degree in aeronautical engineering.

The military had been officially desegregated for fewer than fifteen years when Dwight arrived for astronaut training at the Aerospace Research Pilot School, where he later described facing “an incredible amount of social discrimination.” Dwight completed two phases of training and was one of 26 pilots recommended for a third round, but he wasn’t selected by NASA; he left the military in 1966 and later became a sculptor. There would be no other African American astronaut candidates during the Kennedy administration, and the Soviet Union would fly the first Black person – and the first Latin American – in space in 1980: Lieutenant-Colonel Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez of Cuba.

Messages encouraging the President to select the first black astronaut for space flight, from the White House Staff Files of Harris Wofford and the White House Central Subject Files, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

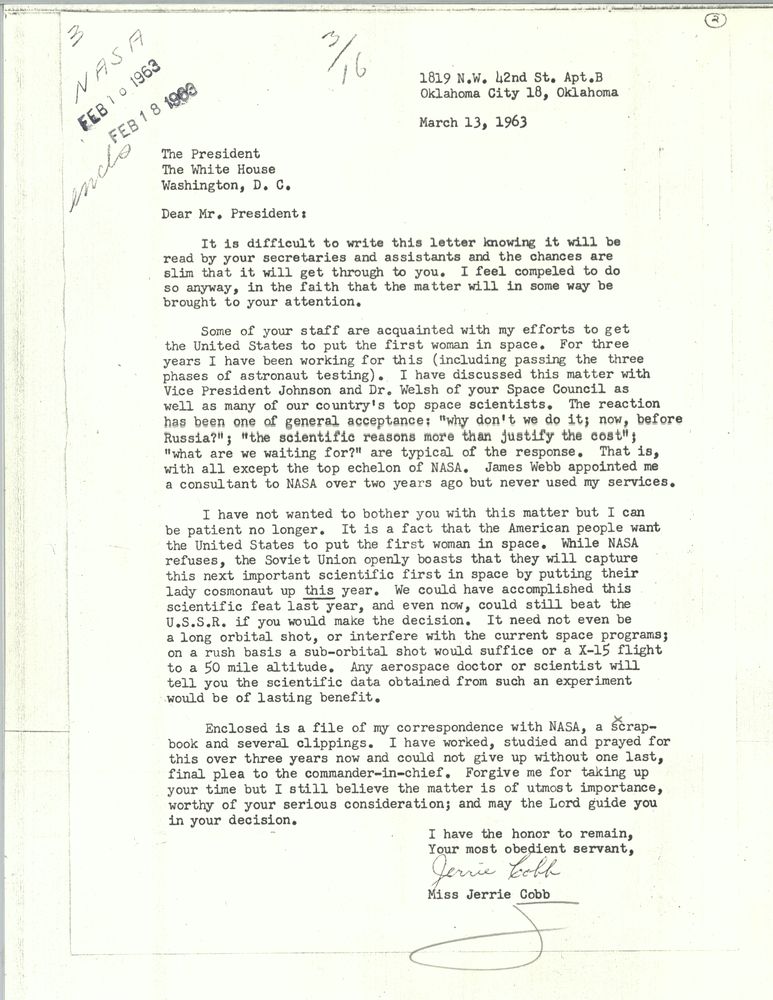

Women’s absence from American astronaut candidate pools didn’t go unnoticed, either – and one person wrote to the White House with a particularly personal interest in the topic: aviator Geraldyn “Jerrie” Cobb. Cobb earned her first pilot’s license at age 16 and went on to set world records for speed, altitude, and distance; at age 28, she was named the 1959 “Pilot of the Year” by the National Pilots Association. Cobb had logged thousands of air hours by 1960, when she and other female aviators were recruited for a privately-funded program that subjected them to the same physical, psychological, and technical tests that male astronaut candidates endured. Cobb passed them all, ranking in the top 2% of candidates of any gender.

In 1962, the Soviet Union launched two manned capsules into orbit at the same time, and Cobb sent a telegram to President Kennedy: “Hope in light of new Russian space achievement you will reconsider my request to discuss with you United States putting first woman into space.” Though she’d been appointed as a NASA consultant the previous year, her request was denied. She wrote again in March 1963: “I have not wanted to bother you with this matter but I can be patient no longer. It is a fact that the American people want the United States to put the first woman in space.”

Her lobbying didn’t convince the government, and Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova would be the first woman in space three months later. Cobb never went to space, but continued to fly for the rest of her career and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1981 for her work piloting relief missions to South America. She noted in a 1998 interview, “I would give my life to fly in space…I would then, and I would now.”

It wasn’t until Dr. Sally Ride’s mission in 1983 that an American woman – and, as the world would learn after her death, a person who identified as part of the LGBTQ+ community – left Earth’s atmosphere. Later that year, Dr. Guion “Guy” Bluford became the first African American in space. As we celebrate these and other iconic achievements in the lead-up to the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, we’re also proud to preserve the records that document lesser-known fights for equal opportunities in the space program, and those who forged a path for the explorers who followed.

Additional sources:

Cobb, Jerrie and Jane Reiker, Woman into Space: The Jerrie Cobb Story, 1963.

Dwight, Edward Jr. Soaring on the Wings of a Dream: The Untold Story of America’s First Black Astronaut, 2009.

Long, Michael G., ed. Gay Is Good: The Life and Letters of Gay Rights Pioneer Franklin Kameny, 2014.

Paul, Richard and Steven Moss. We Could Not Fail: The First African Americans in the Space Program, 2015.

Weitekamp, Margaret A. Right Stuff, Wrong Sex: America’s First Women in Space Program, 2004.