By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

Ernest Hemingway’s papers in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library archives (yes, we have them!) include plenty of items you might expect, like letters and drafts of his many stories and novels. But in addition to being one of the twentieth century’s most famous writers, Hemingway was also a packrat who saved a lifetime of stuff related to his favorite interests: receipts from his best-loved book shops and bars, his packing lists and passports, and decades of jotted-down facts, ideas, and reminders. Archivists grouped these papers – along with everything else that didn’t fit neatly into categories like “Manuscripts” or “Scrapbooks” – into a series called “Other Materials,” and this part of the Hemingway collection is also where we find the fishing, hunting, and boating logs he kept all his life.

Hemingway used his logs to document years of outdoor explorations, writing down where he went and who came along, what he caught and how much it weighed, and even what the weather conditions were like, down to the direction of the wind. They’re a goldmine of information for all kinds of researchers, from literature buffs exploring Hemingway’s inspiration for works like Old Man and the Sea, to scientists looking for historical data about weather patterns and wildlife populations.

But there’s a catch: Hemingway’s adventuring subjected his notebooks to harsh conditions that damage paper and ink. The logs joined him on the open ocean in his beloved boat Pilar, and on his treks through mud, rain, and sunshine in the wilderness of Michigan, Wyoming, and Arkansas. After retiring them from field service, Hemingway stored some of his notebooks in places that make archivists cringe, including attics and basements in humid Florida and Cuba. By the time they came to the archives at the JFK Library, the logs were fragile and unsafe to handle.

Luckily, a rough history and challenging conditions don’t always mean a document is doomed to fall apart, and archivists were recently able to select several of these logs for treatment at a conservation lab. Because imperfections in an historical item can tell us a lot about how its owner used it, making the notebooks look brand new again wasn’t the goal of this conservation project. Instead, we aimed to stabilize the items to slow deterioration and improve access through digital imaging – all while preserving their original character. Now that the notebooks have been treated and photographed, we can share the results, along with some of our favorite details!

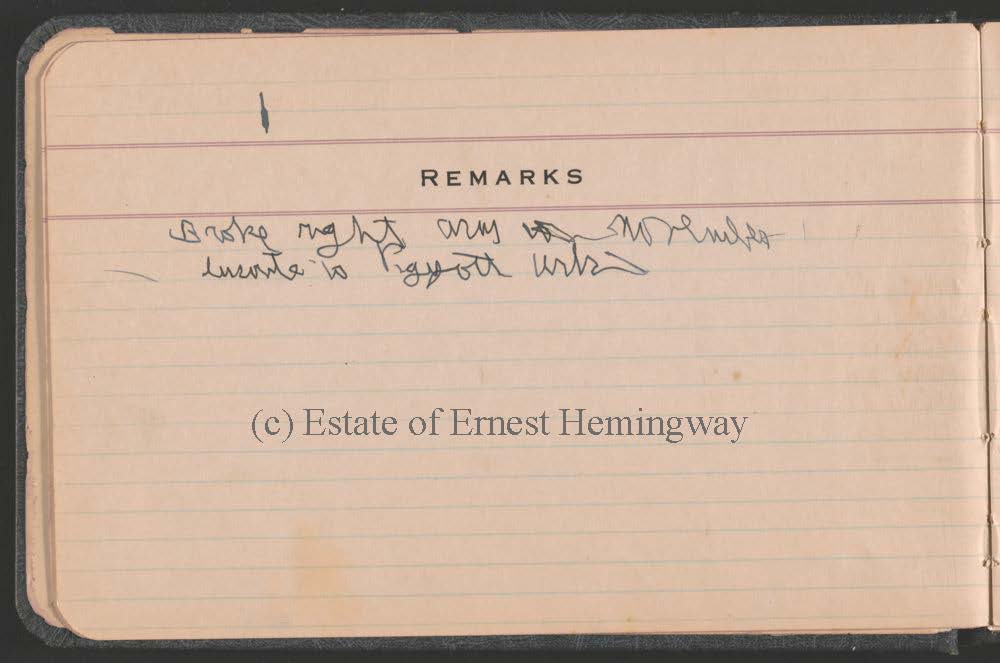

A few of the treated logs provide snapshots of Hemingway’s life in the early 1930s, when he was busy working on his Death in the Afternoon manuscript and pursuing some of his favorite outdoor hobbies. In the fall of 1930, Hemingway filled a few pages of his “Hunting Book” with details about his trip to Montana with fellow writer John Dos Passos, but his tidy notes are interrupted by a few entries in handwriting that is still distinctly Hemingway’s – just a bit sloppier.

His brief written explanation – “Broke right arm November enroute to Piggott Ark[ansas]” – turns out to have been quite an understatement. After spending a night in Yellowstone National Park, Hemingway and Dos Passos were in a car accident, leaving Hemingway hospitalized for most of November and December while he recovered from surgery to repair the fracture. Finally at home in Key West in January 1931, he noted that an attempt to hunt “left handed” had yielded just one snipe; in his separate “Fishing Book 1930-1934,” he wrote that his injury kept him from fishing until the end of March.

In both of these notebooks, Hemingway wrote in pencil and a variety of inks, including the infamous iron-gall ink that can damage paper over time. The notebooks were also stained with dirt, and one was bound in a way that caused the pages to lay crookedly and inaccessible in the volume. At the lab, both notebooks were cleaned, repaired, and fitted for custom storage boxes.

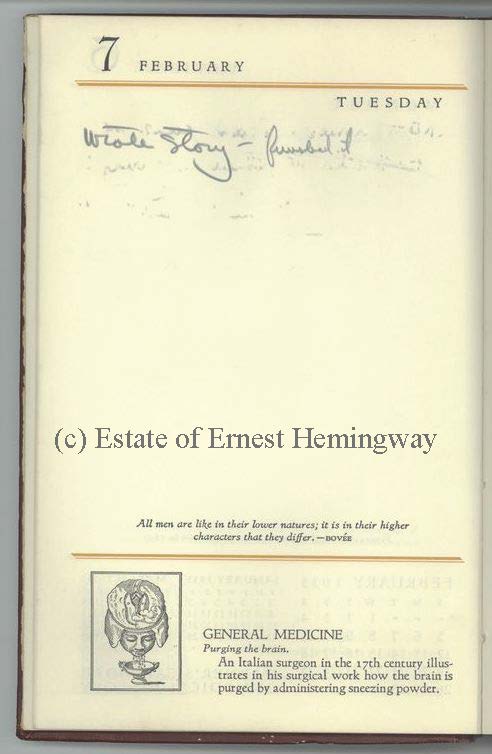

For spring 1933, Hemingway used a Warner’s Calendar of Medical History (a commercially-produced planner with medical facts on each page) as his “Boating Log.” True to form for the author who always seemed to have his work on his mind, Hemingway included writing-related notes between his entries about fishing: for February 7, he noted “wrote story – finished it,” and toward the back of the planner he scribbled “Titles: The Twelve New Joys / The Light of the World.” These notes fit into scholar Michael Reynolds’s timeline of Hemingway’s work; in fall 1933, his short story collection Winner Take Nothing was published, and he’d spent much of that spring and summer thinking about the title and contents of the collection.

Before conservation, this notebook was stained and showed signs of damage from insects and iron-gall ink; it was cleaned and fitted for a storage box that will help slow deterioration. Like all of the treated notebooks, this log will always be fragile; after all, it wasn’t manufactured with the assumption that researchers would want to read its contents for the next seventy years! But now, the combination of conservation and imaging will limit further light and handling damage and ensure the notebooks will be stable for many more years to come.

All Hemingway researchers and fans are welcome to visit the Library to explore the new high-quality facsimiles of these materials; just email us at Kennedy.Library@nara.gov to learn more, or check out the full list of conserved items at the bottom of the post!

With special thanks to the estate of Ernest Hemingway for granting permission to publish images of the logs, and to the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation for funding the conservation of these important documents.

Newly Conserved and Imaged Ernest Hemingway Notebooks:

EHPP-OM14-010. “Notebook: Fishing Book, 1930-1934.” Fishing book; lists fishing trips and describes destinations, type of catch, weights and lengths of catches, flies or bait used, crew, and weather conditions. Pencil and pen. 16 pp.

EHPP-OM14-011. “Notebook: Hunting Book, 1930-1934.” Lists hunting trips and describes the game shot, names of persons on trip, location of trip, and sightings of animals. Pencil and pen. 27 pp.

EHPP-OM14-012. “Notebook: Fishing log, Apr-May 1932.” Labeled “Fishing Log / H.M.S. Anita.” Written both by Ernest Hemingway and Pauline Hemingway in Western Union Cable Blanks pad. 40pp.

EHPP-OM14-013. “Notebook: Fishing Log, May – June, 1932.” Standard School Series. Used as fishing log, May 11 to June 8. Includes notes on Key West house and expenses. Note on Thompson Fish Company receipt inserted. Pencil. 24 pp.

EHPP-OM14-014. “Notebook: Boating Log, Jan – May 1933.” Calendar 1933. Used as boating log, listing outings from Jan 25 through May 15. Describes locations, crew, weather conditions, fish caught, and activities such as the completion of a story. Pen and pencil. 61pp. w/notes.

EHPP-OM15-001. “Notebook: Boating Log, Feb 1933.” Calendar 1933. Used as a notebook with one log entry on Feb 22 for a boating trip. Notes on prices for various sizes of miscellaneous fish. Pencil. 6pp. w/notes.

EHPP-OM15-002. “Notebook: Boating log: Cuba trip, 1933.” Record Book. Used as boat log for “Cuba Trip 1933.” Pencil. 112pp.

EHPP-OM15-003. “Notebook: Fishing Log of the Pilar, 1934-1935.” Log of the Pilar for fishing trip based in Cuba. Carbon of typescript prepared by Arnold Samuelson from dictation by EH. Entries dated from 28 July 1934 through 2 February 1935. 95pp.

EHPP-OM16-003. “Notebook: Fishing Log, 1939.” Calendar 1939. Used as fishing log primarily between Apr 7 – Aug 12, containing notes as “worked on novel.” Contains 7 fragments within its covers: lists, notes, receipts. Pencil.

EHPP-OM16-005. “Notebook: Pilar Log, [1942].” Leather bound calendar for 1941 with Ernest Hemingway’s name on front cover. Log for Pilar during World War II Caribbean activities. 113pp.

EHPP-OM16-007. “Notebook: Pilar Log, 1945 – 1949.” Log of the Pilar for various trips, with entries by EH, MH and “R.O.T.” 19pp.

EHPP-OM16-009. “Notebook: The Old Man and the Sea, 1955.” Block para Calculos No. 40341/2. Notes on renting and purchasing boats and equipment for the filming fishing sequences for The Old Man and the Sea. Ink and pencil. 2pp.

AH! It seams fishing is something smart people do, I really proud of myself! really all things aside I really enjoy reading Hemingway’s journey, thanks for sharing though 🙂

[…] IGFA, including Michael Lerner, William King Gregory, Van Campen Heilner, and Ernest Hemingway, an avid fisherman who included detailed descriptions of sport fishing and game fish in his […]

Great post on Hemingway and his notebooks. Very educational. We also feature Hemingway in our educational and motivational blog: https://mathtuition88.com/2015/11/13/motivational-quotes-and-stories-for-students/

The pleasure of fishing is incredibly beautiful. A great informative article.

Can I share your post on Hemingway with my students?

You are welcome to share the post with your students. Thanks for reading!

Congrats on an informative post my friend. I am waiting for the continuation of such informative articles.

As a Floridian, I appreciate learning more about Hemingway and especially the Key West house.

[…] Ernest Hemingway: The American novelist and short story writer kept a journal to record story ideas and everyday details that he observed. By carrying the notebook with him everywhere, Hemingway could note every detail and infuse his writing with richness. […]

[…] Ernest Hemingway: The American novelist and short story writer kept a journal to record story ideas and everyday details that he observed. By carrying the notebook with him everywhere, Hemingway could note every detail and infuse his writing with richness. […]