By Emily Mathay, Graduate Student Intern (Simmons University)

Emily is a CODA (Child of a Deaf Adult) and is fluent in American Sign Language.

National Deaf History Month (March 13 – April 15) celebrates and promotes awareness of American deaf history and culture. Here at the JFK Library, we’re closing out the month with materials from our archives that document some experiences of members of the deaf community in the 1960s.

While American Sign Language (ASL) has been used in the United States since at least the early 1800s, it wasn’t until the 1960s that it began to be widely recognized by both linguists and the hearing public as a language of its own. But even with the more prominent rise of Deaf culture and American Sign Language, deaf individuals were – and still are – continually dealing with issues of access and communication. Before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (requiring employers, businesses, and others to provide “reasonable accommodations” that ensure effective communication), the deaf community fought for equal access and found that not everyone recognized that communication requires effort from all sides.

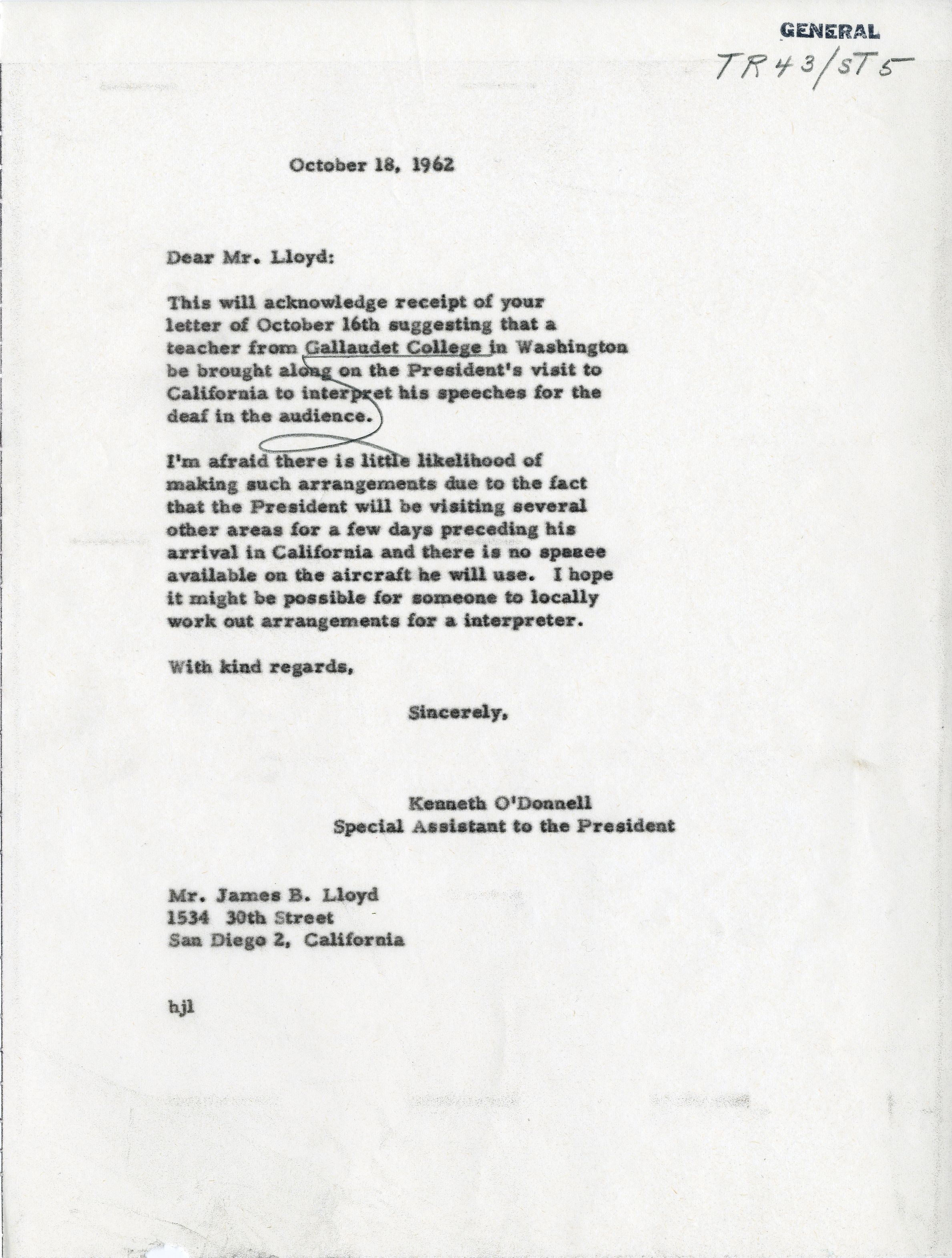

It can often be hard to find archival documentation of this fight beyond the work of well-known advocates like Helen Keller, but it does appear in glimpses throughout the JFK Library’s holdings – especially in letters and interactions between the Kennedy administration and the general public. The White House response to one citizen’s request for an ASL interpreter at an upcoming Presidential speech reminds us that even as ASL was becoming a larger part of the public consciousness, the responsibility of ensuring access and communication was often placed on people who are deaf.

“I’m afraid there is little likelihood of making such arrangements…I hope it might be possible for someone to locally work out arrangements for a interpreter.”

Kenneth O’Donnell letter to James B. Lloyd, October 18 1962

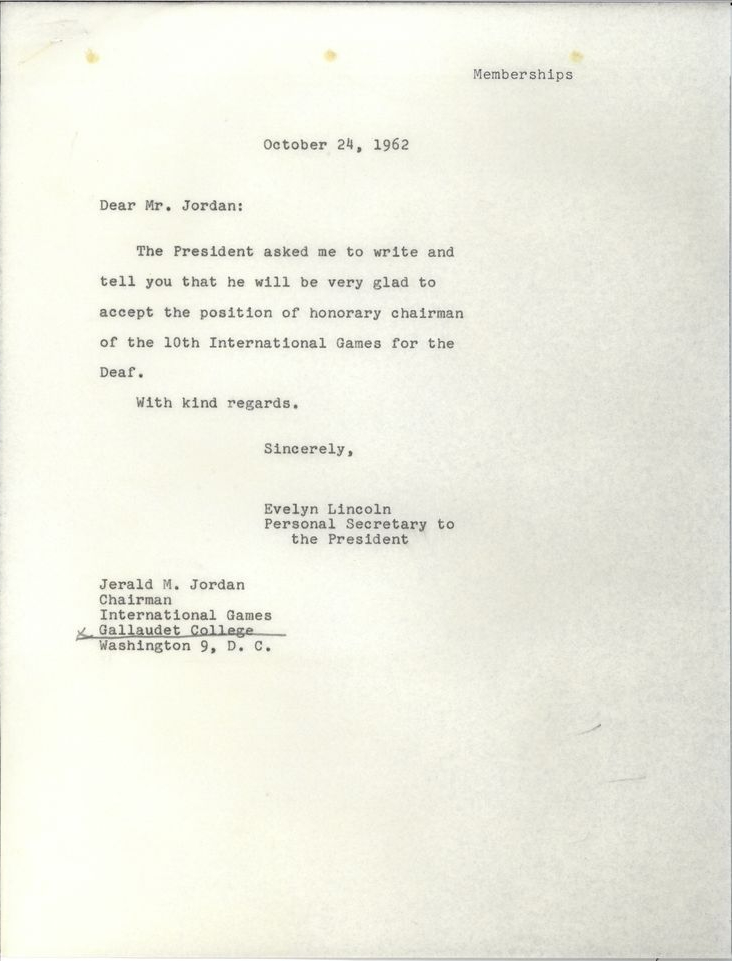

Throughout the 1960s, the American deaf community continued to advance visibility and awareness. In the summer of 1965, advocates enjoyed an unprecedented success as 696 athletes from 27 countries gathered in Washington, D.C. for the 10th International Games for the Deaf (now more commonly called the “Deaflympics”), marking the first time they had been hosted outside of Europe. Three years earlier, President John F. Kennedy had accepted a position as Honorary Chairman of the Games.

Though he did not live to see the 1965 Games (President Lyndon B. Johnson opened the Games), John F. Kennedy did meet with some of the Games’ representatives at the White House in 1962. The guest list included Director Thomas Berg, Chairman Jerald Jordan, and several athletes who competed in the 1961 Games in Helsinki: Mary Lynch (long jump); Nancy Mahoney (swimming); John Miller (basketball); and William Ramborger (javelin and triple jump).

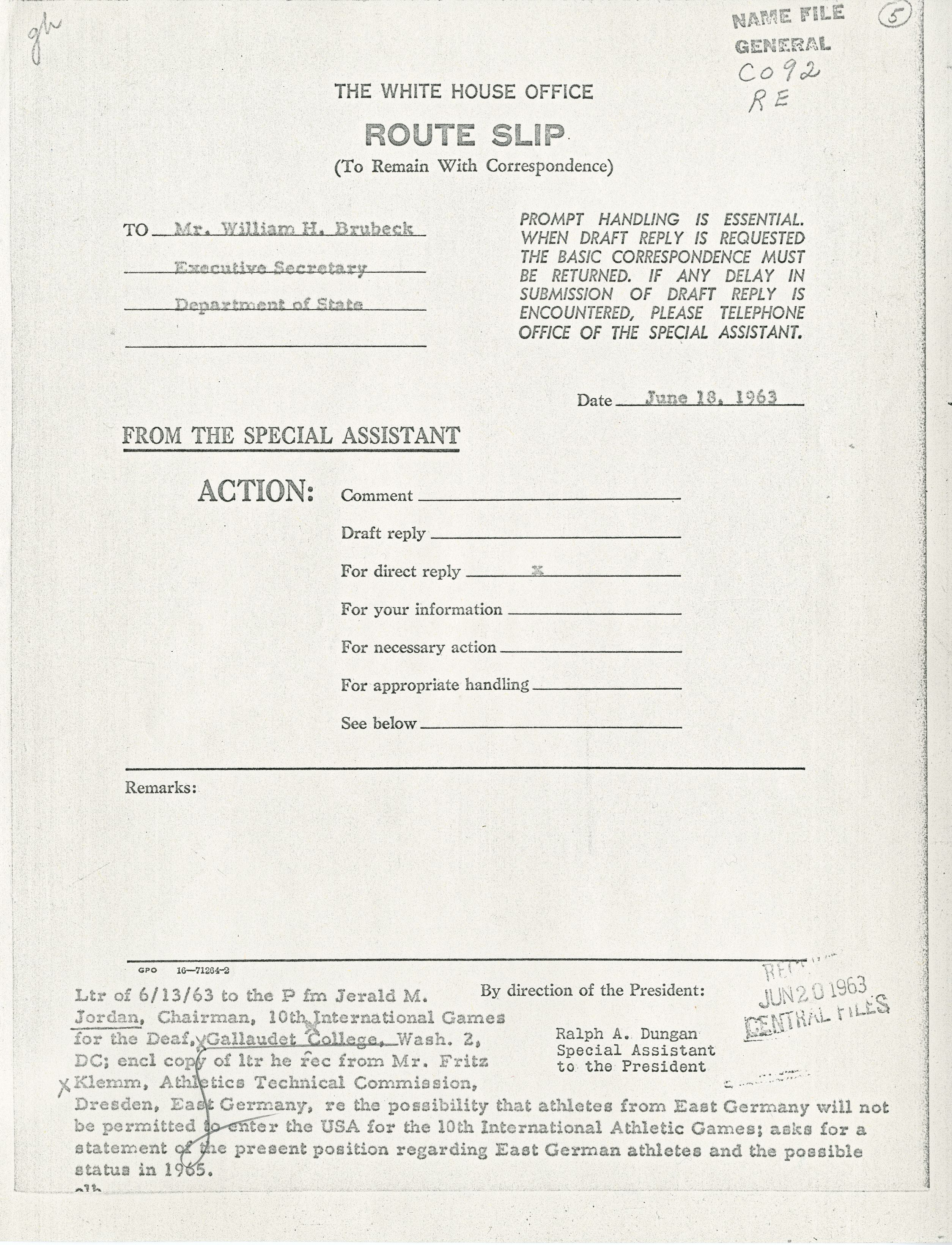

In 1963, one of the Games representatives who had met with the President (Chairman Jerald Jordan) sent a letter to the White House expressing his concern that athletes travelling to the U.S. from East Germany, most likely as members of a united German team, would not be permitted to enter the United States to compete. Archivists haven’t yet found a response to Chairman Jordan’s inquiry, but we do know that Germany sent a total of 56 athletes to the 1965 Games (and completely dominated table tennis)!

Though these records provide a glimpse into the lives of some deaf individuals, it is still hard for the deaf community to find itself represented in most archives – as is the case for many communities that fight for equal rights in their daily lives. People who are deaf are often still unacknowledged in classrooms, workplaces, movie theaters, and even in the study of history. Uncovering documents that can shine a light on the community’s experiences is one small step in the right direction.