(A version of this post was published on our previous blog on 3/19/2013; we’ve republished it in honor of Black History Month.)

By Tara Mayes, Former Graduate Student Intern (UMass Boston)

I began my career at the Kennedy Library as an intern eager to work in an institution dedicated to historical research and interpretation. I have to admit, however, that before coming here I had basic (aka, grade school) knowledge of John F. Kennedy. As a graduate History student at UMass Boston, I narrowed my focus to Native American, African American, and early nineteenth-century maritime history. So when I was first asked to create a bulletin board focusing on civil rights during the Kennedy Administration, I was a little hesitant. The Kennedy Library is a treasure chest of incredible documents regarding the subject, and choosing a select few to cover the 45 x 33-inch space was daunting. In taking the risk, however, I experienced a journey that not only enriched my historical knowledge but also helped me to reflect and create a new understanding of history.

The year 2014 marked the 50th anniversary of “Freedom Summer,” the historic, volunteer-led campaign to register Black Mississippians to vote during the summer of 1964. I approached the task by selecting documents that thematically demonstrated the road to civil rights as a journey. This is not to say that 1964 marked the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. American citizens, especially those of color, began demanding their equality long before the 20th century. The Civil War ended in 1865, and since then men and women turned a mirror to the American government, asking them to reflect on the basic principle that founded this country: “All men are created equal.” Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954 amended a ruling created 100 years earlier that separate did not inherently mean equal. The Freedom Rides began in 1961, when students on integrated buses risked their lives traveling south in protest of segregation on public transportation. In 1962, James Meredith initiated the integration of Ole’ Miss. All of these events were steps on a larger journey highlighting an issue of inequality in American society that led up to 1964.

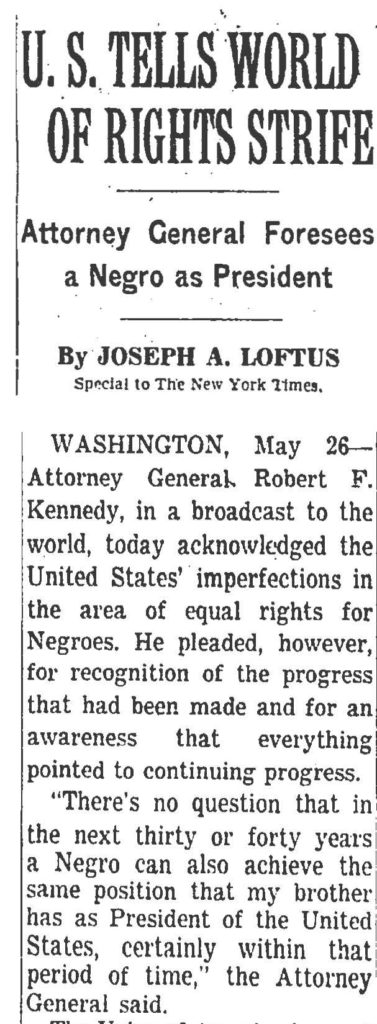

I wanted observers to recognize the journey up to that year. The board started with a small recap of events leading up to Freedom Summer, including a 1961 New York Times article with a caption that read, “Attorney General Foresees a Negro as President.” The article summarized an interview in which Robert F. Kennedy expressed the importance of establishing equal rights for African American citizens:

In the next thirty or forty years a Negro can also achieve the same position that my brother has as President of the United States…

The New York Times, May 27, 1961.

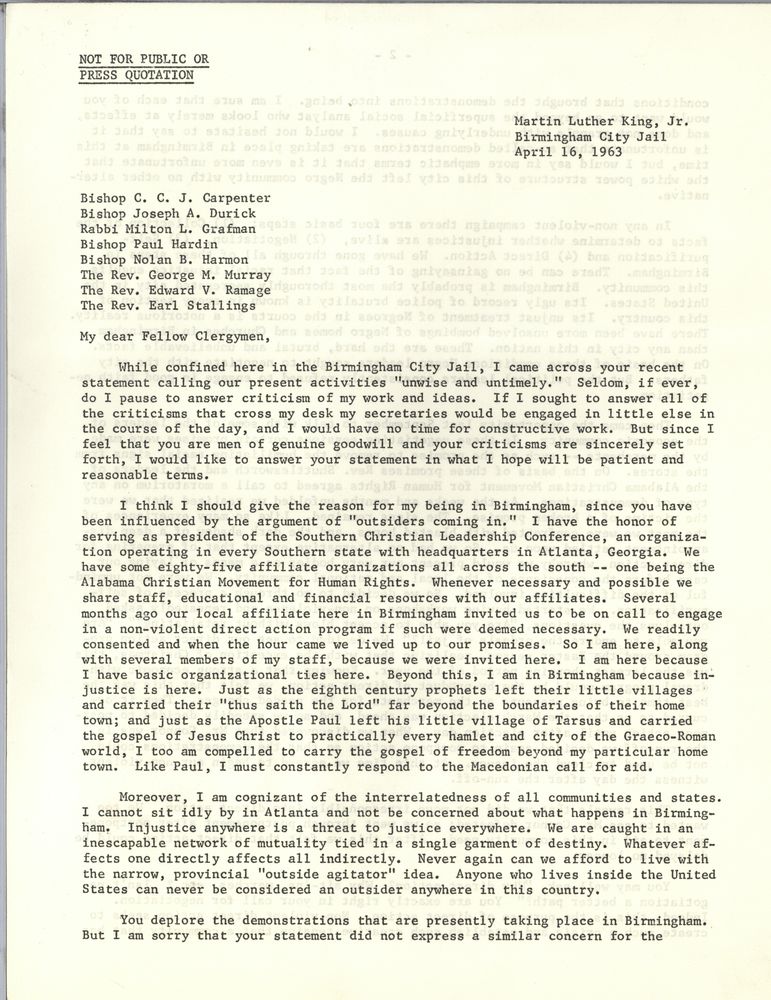

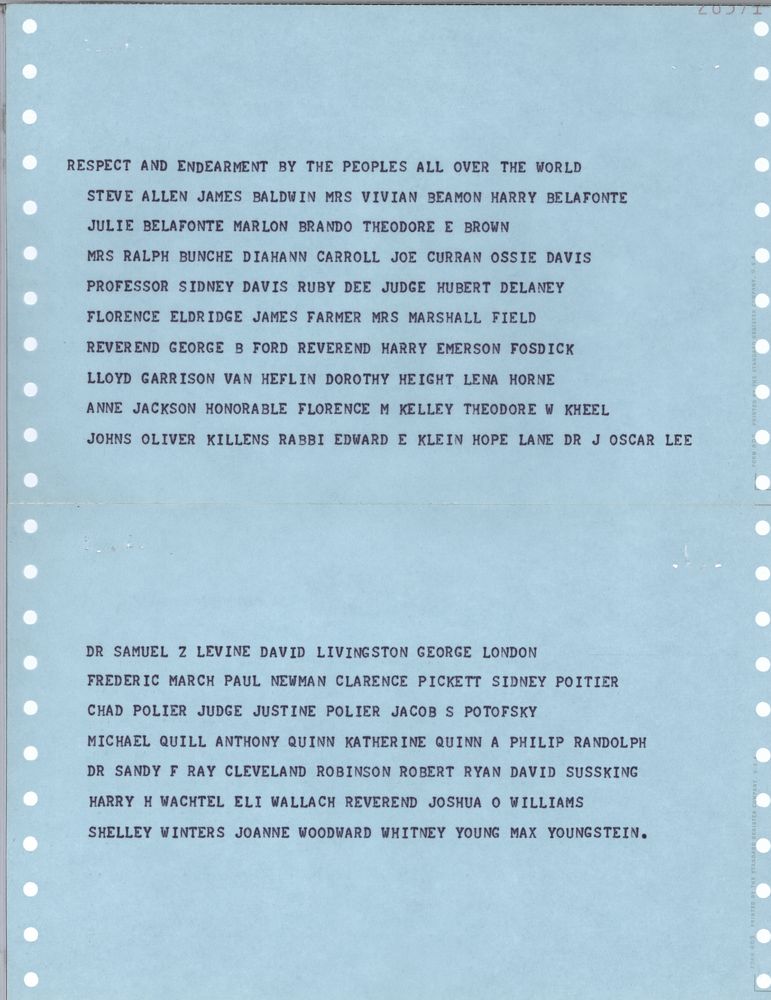

The display then moved to April 1963 and featured Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which he wrote after his arrest for participating in demonstrations in Birmingham. I also included a telegram sent to the President in response to King’s arrest. I found the telegram to be exciting, as people such as Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Lena Horne, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, and Marlon Brando added their names to the many demanding King’s release.

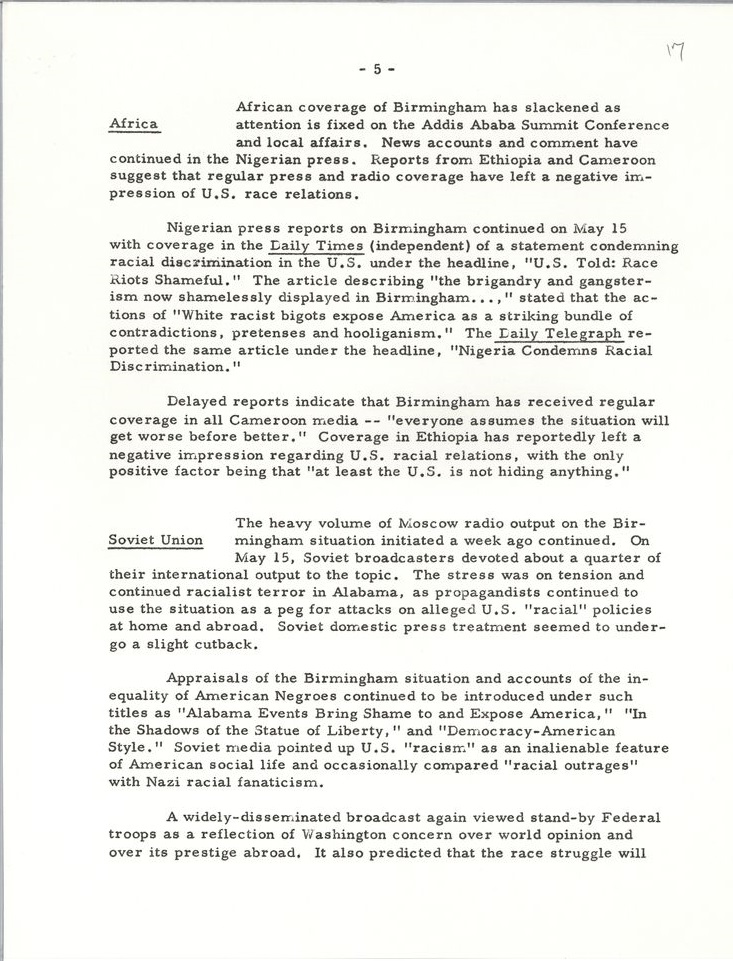

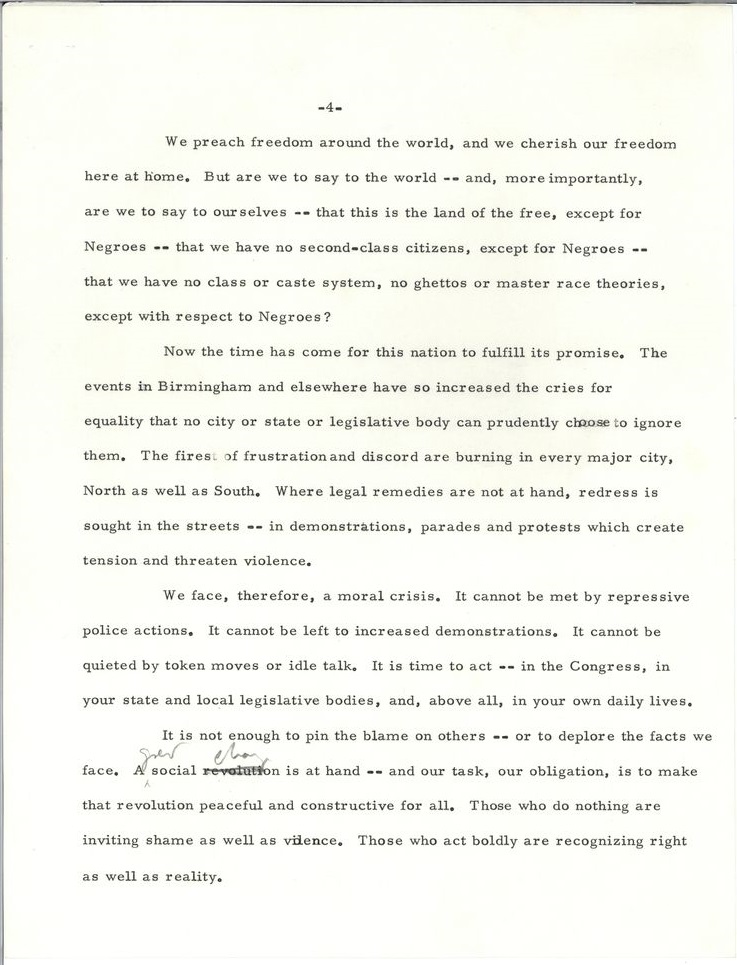

Another interesting document I chose was a summary of global reactions to the civil rights demonstrations and the violence protestors endured. This document illustrated the Kennedy Administration’s keen awareness that America projected a negative image overseas with regard to civil rights and the treatment of protestors. This was the era of the Cold War; it would be hard to criticize Communism and preach democracy and freedom when people were beaten and killed for asking for rights in a country founded on those principles.

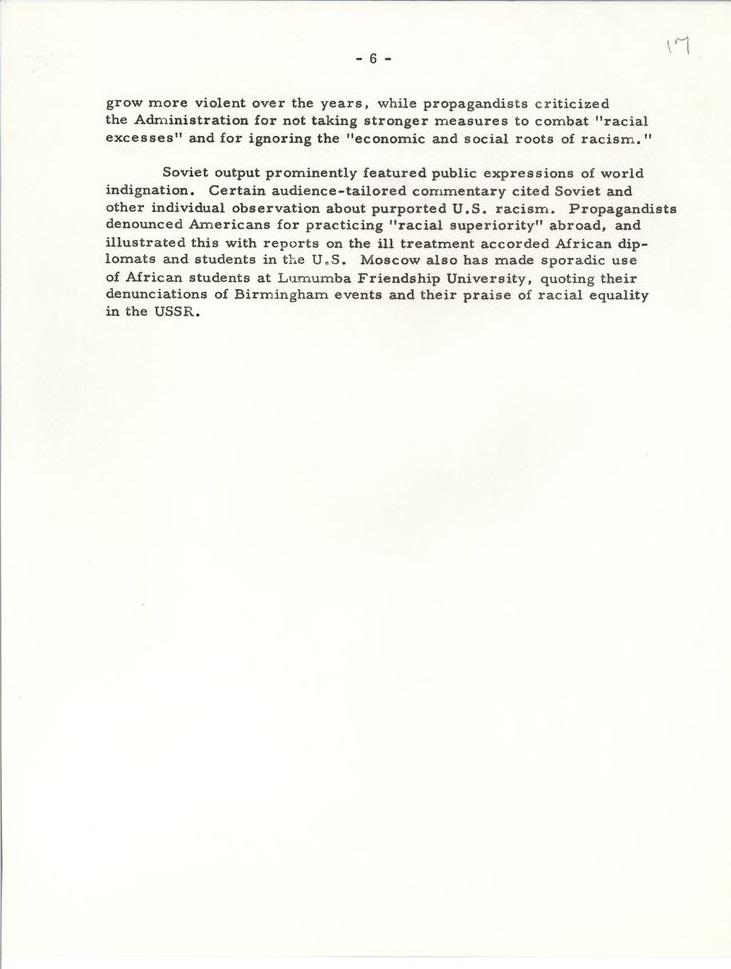

I also decided to add two telegrams from Alabama Governor George Wallace to President Kennedy. In the telegrams, the Governor condemned what he saw as the abuse of states’ rights and the violence and disruption civil rights protestors were carrying out in Birmingham. I juxtaposed the telegrams with a Charleston newspaper article that provided graphic images of protestors being attacked with fire hoses and police dogs. For me, the juxtaposition visually reflected the propaganda versus the reality.

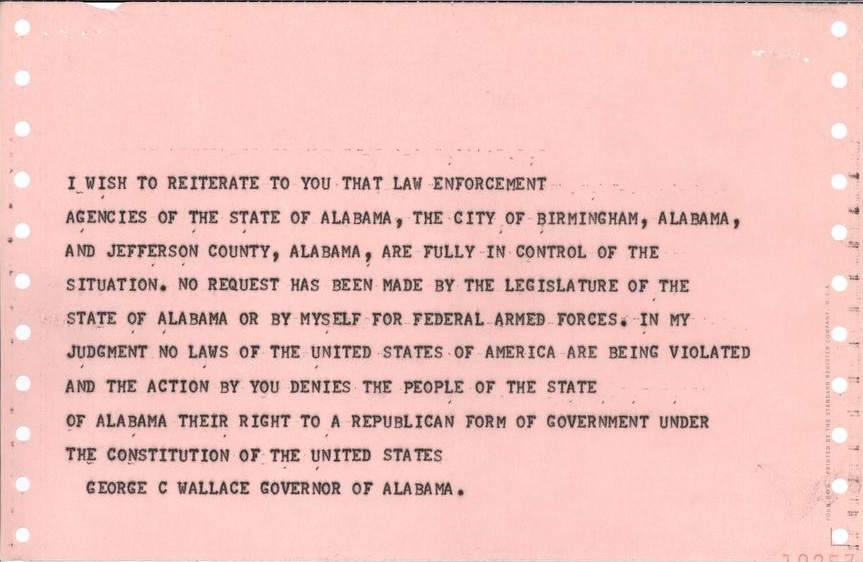

The display transitioned to June 11, 1963 when the President delivered his “Radio and Televised Address to the Nation on Civil Rights”. Instead of displaying a reading copy of the speech, I chose instead to exhibit a draft authored by Theodore Sorensen, speechwriter and Special Counsel to the President. I found the drafts especially interesting because of President Kennedy’s edits; I noticed that he substituted some of Sorensen’s words that may have appeared too provocative or alienating, putting in language that could be seen as less inflammatory. For example, on the fourth page of the second draft, Sorensen wrote, “A social revolution is at hand—and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution peaceful and constructive for all…” The President scratched out the word “revolution” and replaced it with “change”—though ultimately used the word “revolution” in his final delivery.

Next to the draft was a note directing the observer to the Kennedy Library website where they could listen to or watch the speech as it was delivered by the President. The speech reflected a sense of urgency regarding civil rights, especially during the last couple of minutes, when President Kennedy went off script and explicitly detailed the need for change.

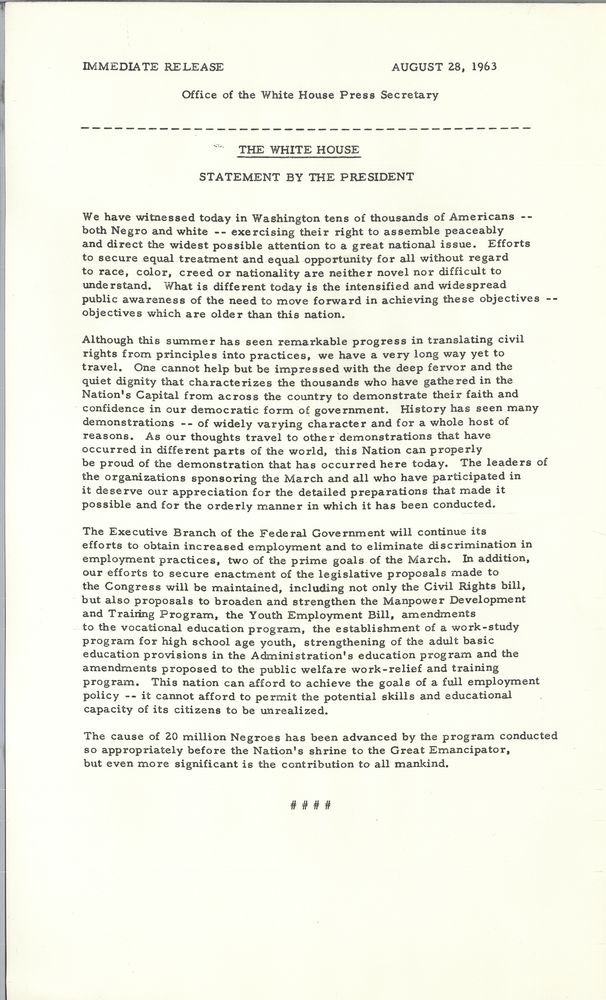

The bulletin board ended, fittingly, in August 1963, marking the end of summer. That month brought the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. On the board, I chose to display a copy of the press release from the President’s Office endorsing the march:

We have witnessed today in Washington tens of thousands of Americans — both Negro and white — exercising their right to assembly peaceably and direct the widest possible attention to a great national issue… What is different today is the intensified and widespread public awareness of the need to move forward in achieving these objectives — objectives which are older than this nation.

Although this summer has seen remarkable progress in translating civil rights from principles into practices, we have a very long way yet to travel.

President Kennedy’s assessment proved accurate, for that summer did not mark the end of the journey. It was not until after President Kennedy’s assassination that President Lyndon B. Johnson was able to pass the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964.

I enjoyed creating the board because it was a learning experience for me. When first asked to tackle the challenge, I thought that I would depict the subject matter in a simple, creative way to pique the interest of visitors to the research room. I did not think, however, that during the process I would discover my own interest in the subject, which had nothing to do with my primary research on early nineteenth-century maritime history. I could not have been more wrong. In telling the story of the journey of brave individuals involved in the Civil Rights Movement, I saw links to my own work: individuals constantly fighting and struggling for freedom, equality, and citizenship that stretched before the Civil War. The summer of 1963 was a summer of change, in which President Kennedy struggled on his journey, trying to balance and uphold the law while avoiding alienating southern white citizens. His June 11 speech, for me, marked his realization that the importance of the issue outweighed fear of division. The summer of ’63 reflected the long and tumultuous journey for African American people and their fight for freedom against the bondage of second-class citizenship.

Doing the board reminded me of why I chose to be a historian and how the lessons and events of yesterday still pertain and are very much relevant today. History always amazes and surprises me from the lessons it can teach; it is absolutely incredible and slightly eerie that I get to live during the time that Robert F. Kennedy predicted, understanding that the importance in having equal rights did not end in 1963 or even in 1964 with the passing of the bill; it is a continual struggle. So I think ahead, to the intern in the Research department at the Kennedy Library fifty years from now, having just received the task of commemorating the 100th anniversary of Freedom Summer of 1964. What new discoveries will emerge then?