By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

The experiences of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) through history are as diverse as the AAPI community itself, which includes people with origins anywhere on the Asian continent and the Pacific islands that make up Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. While many Americans can name a few famous people of AAPI heritage through the country’s history (architect I.M. Pei or movie star Anna May Wong, for example) the lives and stories of AAPI people are still underrepresented in histories of the United States.

For this year’s Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month, we’ll be bringing some of these stories out of the archives at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. An archival photograph is the window into our first story, but the story behind this photo begins long before the moment it was captured.

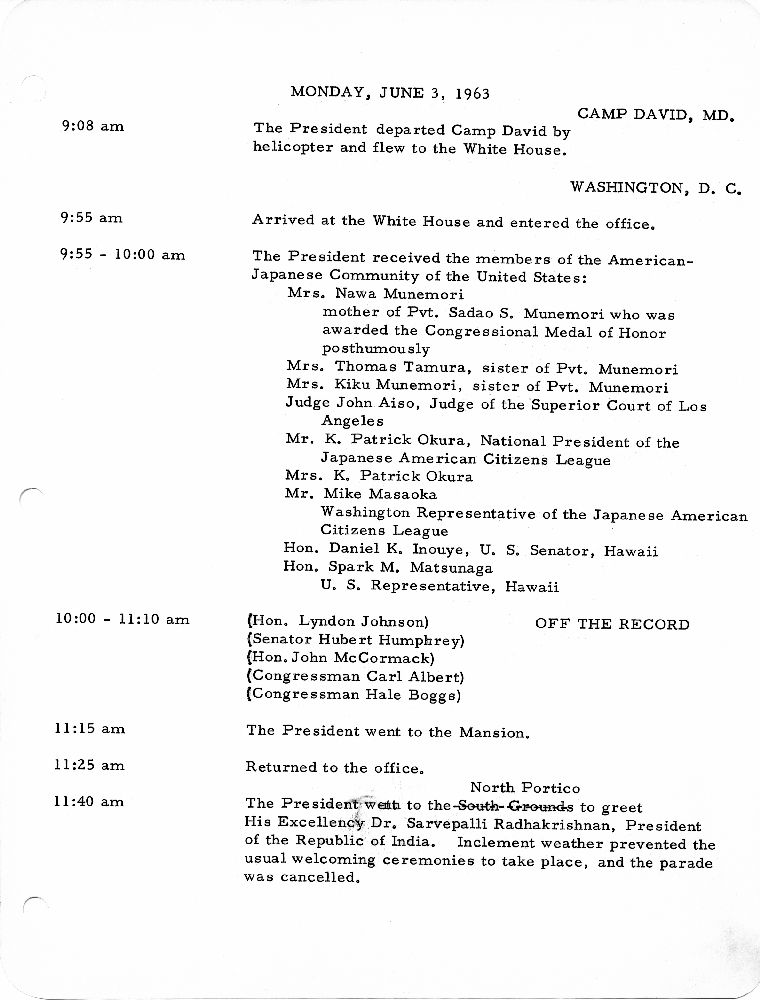

In this image from June 3, 1963, President John F. Kennedy stands with a group of nine Japanese American visitors in the White House. The President’s appointment book tells us who was there: Nawa Munemori and her daughters Kiku Munemori and Yuriko Munemori Tamura; the President of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) K. Patrick Okura and his wife Lily Okura; JACL’s Washington Representative, Mike Masaoka; Judge John Aiso of the Superior Court of Los Angeles; Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii; and Representative Spark Matsunaga of Hawaii.

But there’s a question the appointment book doesn’t help with: what brought all of these people – a private family, government leaders, and civil rights activists – together for a visit to the White House on this June day? Exploring each of their stories illuminates the connections behind this photo – and the struggles and resilience of the Japanese American community in the twentieth century.

The munemori family

Twenty-two years before Nawa Munemori’s visit to the White House that day, her 19-year-old son Sadao Munemori enlisted in the U.S. Army. Like all Japanese American soldiers after the Japanese military’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Munemori was banned from serving in combat. Japanese Americans in and outside the military spoke out against the policy, and in 1943, a segregated combat unit of second-generation Japanese Americans (Nisei) was created: the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Munemori and over 4,000 other Nisei soldiers volunteered to join.

Meanwhile, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the imprisonment of 122,000 people of Japanese ancestry in the United States – including Munemori’s mother Nawa and his three sisters, who were incarcerated in California’s Manzanar internment camp. According to later interviews, Nawa Munemori and her daughters were still imprisoned in Manzanar when they learned that Sadao had died in action in 1945; he had thrown himself on top of a German grenade in the Italian mountains to save his fellow soldiers from the blast.

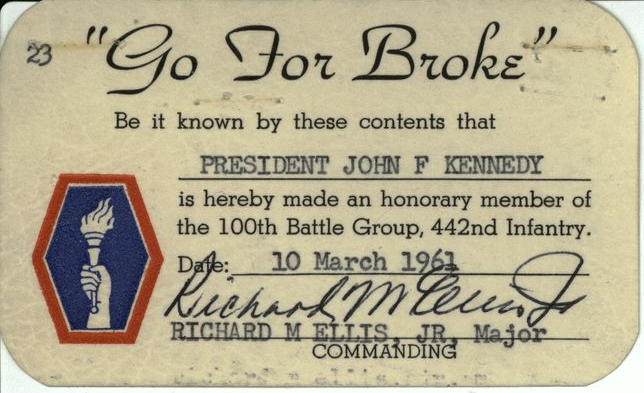

In March 1946 – the same month that the last federal internment camp closed – Nawa Munemori accepted a Medal of Honor on behalf of her son, the first Japanese American to be awarded the nation’s highest military honor. Known as the “Go For Broke” unit, the 442nd went on to become the most decorated military unit in U.S. history.

Japanese American Public Servants

During their 1963 visit to the White House, the Munemori family were joined by Japanese American public servants who’d achieved a number of American “firsts”: Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii (the first Japanese American member of both the House and the Senate); Representative Spark Matsunaga of Hawaii; and Judge John Aiso of the Los Angeles Superior Court (the first Japanese American judge in the contiguous United States).

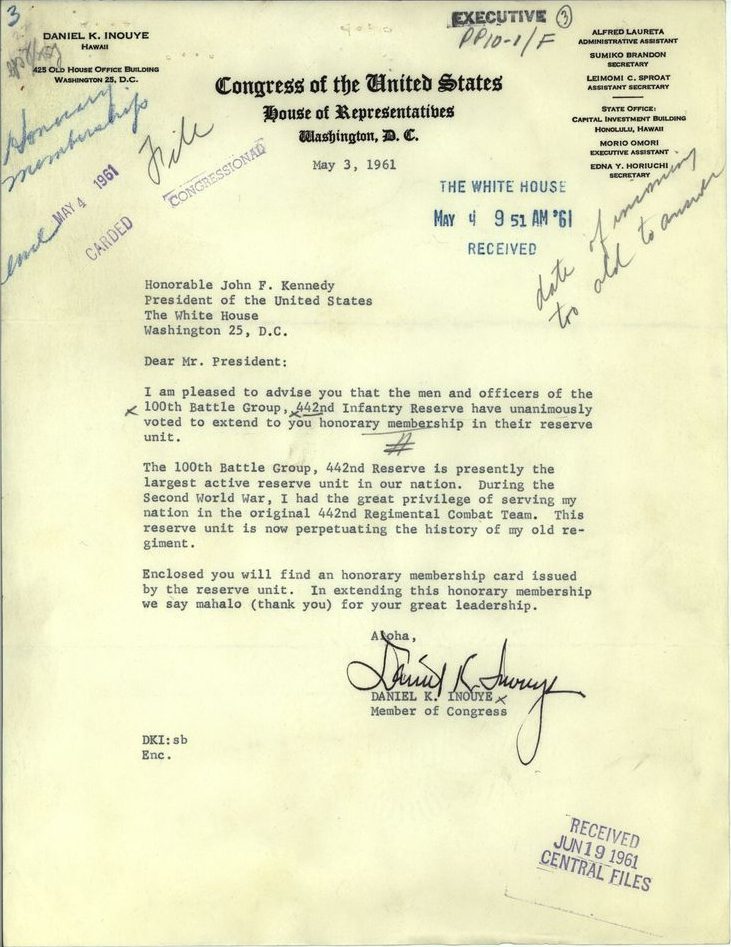

During World War II, all three served in the U.S. military. Aiso was an instructor in the Military Intelligence Service Language School; though Nisei service members were broadly banned from becoming commissioned officers, Aiso’s skills caught the attention of commanders who granted an exception, making him the highest-ranking Japanese American in the Army during World War II. Meanwhile, both Inouye and Matsunaga signed up for combat with the 442nd and were seriously injured while fighting in Europe; Inouye lost his right arm and was later awarded a Medal of Honor. Each of these public servants continued to raise awareness of Nisei soldiers in World War II, and in 1961, Senator Inouye sent a letter to the President about his time with the 442nd, along with an honorary combat unit membership card.

leaders of the japanese american citizens league

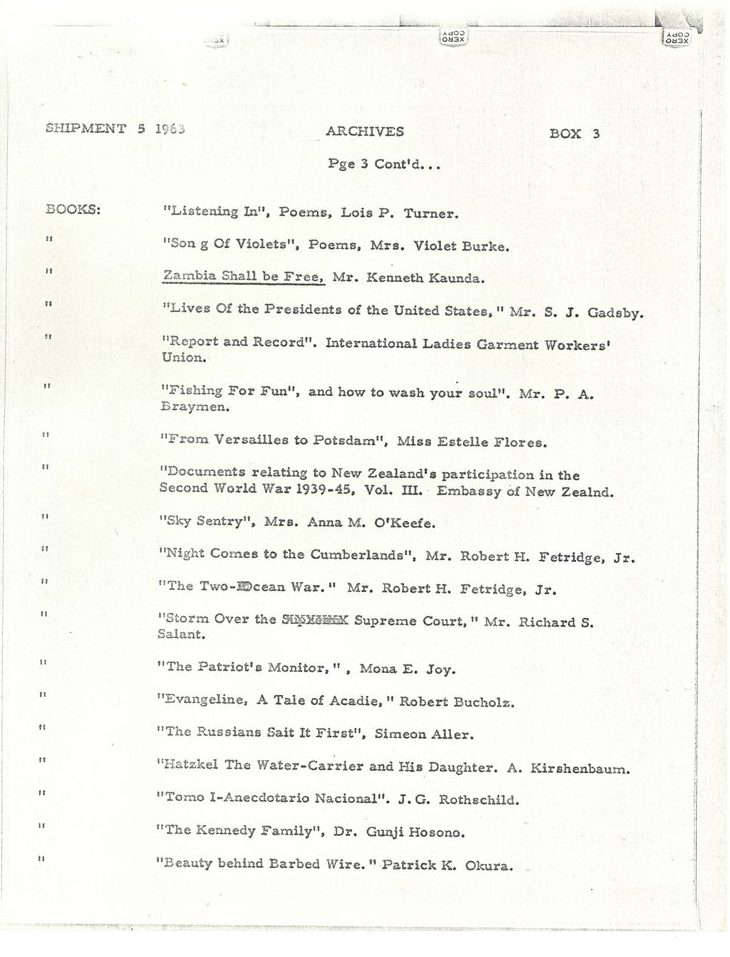

The remaining members of the group pictured with the President were leaders in the country’s oldest Asian American civil rights organization, the Japanese American Citizen’s League (JACL): JACL President K. Patrick Okura and his wife Lily Okura, and JACL Washington Representative Mike Masaoka. Each came to their civil rights activism through different routes. Psychologist K. Patrick Okura and his wife Lily had been married only a few months when their lives were upended by E.O. 9066; they were imprisoned together at an internment camp outside of Los Angeles for eight months. After the war, the Okuras became leaders in civil rights and public health, and they continued to raise awareness about the structural racism that led to their incarceration. Records in the JFK Library’s archives show that K. Patrick Okura sent a book to the President in 1963: Allan H. Eaton’s Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of the Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps.

During World War II, Mike Masaoka advocated for the creation of a Nisei combat unit and was one of the first to sign up with the 442nd; he played a controversial role in recruiting for the 442nd by encouraging Japanese Americans to enlist in order to prove their loyalty to the United States. Masaoka stayed active in public relations for the JACL after the war, and lobbied Congress for a bill that would allow Japanese immigrants to become U.S. citizens; the bill was signed into law in 1952.

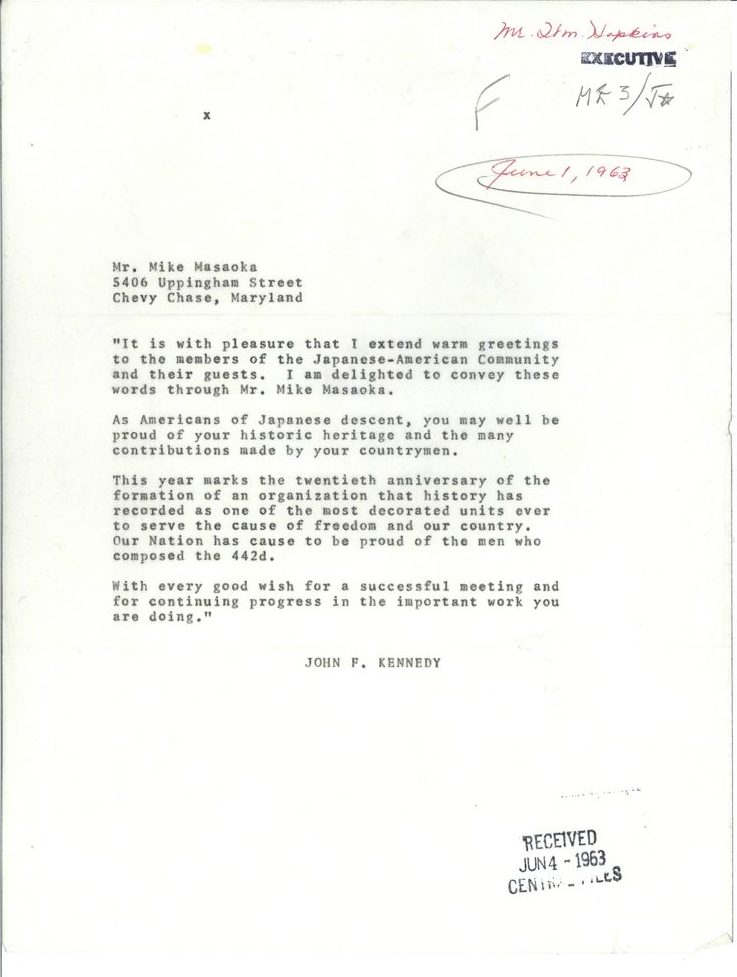

Masaoka’s work also generated an important clue about the June 3, 1963 group meeting with the President: a letter from the President to Masaoka, dated June 1, 1963, that greets the Japanese-American community on the 20th anniversary of “an organization that history has recorded as one of the most decorated units to serve the cause of freedom and our country” – the 442nd.

honoring the 442nd Regimental Combat Team

Through archival material, historical newspaper coverage, and their own stories, the connection between each of these White House guests emerges: they had all come to Washington for a ceremony honoring the 442nd Combat Team’s 20th anniversary. The Associated Press reported that the memorial ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery was organized by the Japanese American Citizens League on June 2, 1963, and speakers included Senator Inouye, Representative Matsunaga, and Judge Aiso; K. Patrick Okura placed a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns, while Nawa Munemori was “the special guest of honor.”

The press also noted that the ceremony’s distinguished guests would visit the White House the next day on a trip arranged by Senator Inouye and Representative Matsunaga. At the White House, Senator Inouye presented President Kennedy with a copy of the book Americans: The Story Of The 442nd Combat Team by Orville Cresap Shirey. After the meeting, the President told reporters:

“I appreciate the gift of the story of the 442nd Combat Team, which I think is an outstanding story of American courage, and we are glad to welcome to the White House particularly this outstanding American [Nawa Munemori].”

In commemorating the anniversary of the 442nd Combat Team, the Munemori family, the Japanese American Citizens League, and Japanese American public servants raised public awareness of the sacrifices of Nisei soldiers who served their country while national policies limited their opportunities and imprisoned their family members at home. Archivists at the JFK Library are honored to preserve the records that document these stories, during Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month and all the years to come.

You can learn more about Japanese Americans in the mid-twentieth century through the Densho Encyclopedia and Digital Archives; the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center; and the National Archives Japanese American Internee Data File.

This is incredible. While members of their families were in internment camps, these brave soldiers defended the country that they loved.

So good to see that their contributions are acknowledged. So many went on to build the multi national country that the USA is.

Thank all of you.

George Takei, Star Trek’s Lieutenant Sulu was in an internment camp in WW II. He went on to serve in Starfleet! Gotta love it.