By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

Keeping up with global politics in any era can be a challenge; with so much information to sift through, it can be tricky to know exactly what to focus on. This can be an even bigger problem for the President of the United States, who relies on the huge volume of information collected by multiple federal agencies to make decisions – and it’s a problem that’s partly solved by the highly-classified President’s Daily Brief, or PDB. With the PDB, intelligence experts condense the details they think the President should know about world events into a document that’s just a few pages long, which is then hand-delivered to the White House each morning.

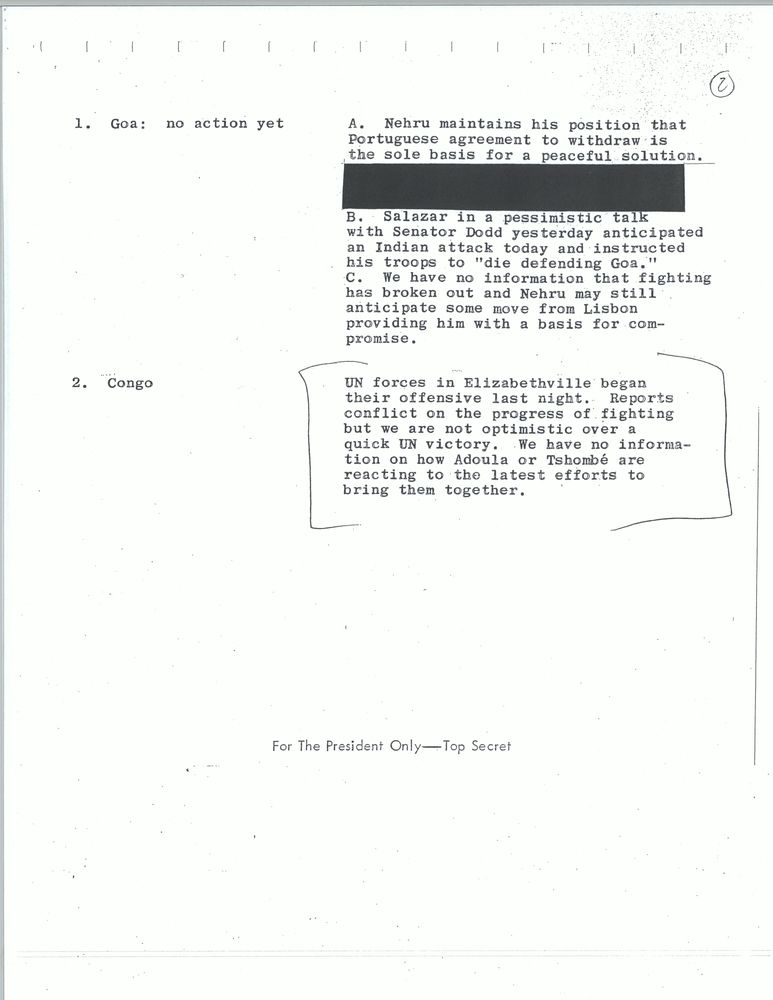

The modern PDB is produced by the Director of National Intelligence, but in John F. Kennedy’s era, the briefing was created by the Central Intelligence Agency. Back then, a consolidated daily update was still a pretty new concept – having premiered during President Harry S. Truman’s administration in 1946 – and the CIA tried a few versions before landing on what they called the President’s Intelligence Checklist, or PICL (pronounced “pickle” by White House staff). Though the CIA once considered PICLs too sensitive to declassify, CIA staff and JFK Library archivists reviewed and opened much of the PICL material in our holdings between 2012 and 2019, and we’ve recently completed digitizing and cataloging these records for online public access. We’re excited to share these materials with you!

The PICLs have been preserved in the National Security Files collection for nearly 60 years, thanks to the work of Military Aide General Chester “Ted” Clifton. General Clifton was responsible for coordinating the PICL briefings, and as retired JFK Library Declassification Archivist Maura Porter has noted:

“The writing on the first page of the PICL is usually in General Clifton’s hand and indicates whether the President saw that particular PICL. Clifton’s notations – ‘P saw’; ‘P not seen’; or ‘Pres has seen’ – can be distinguished from another (unidentified) staff person’s notation, ‘President read.'”

Maura Porter, “New Release of the President’s Intelligence Check Lists (aka PICLs),” 1 August 2012.

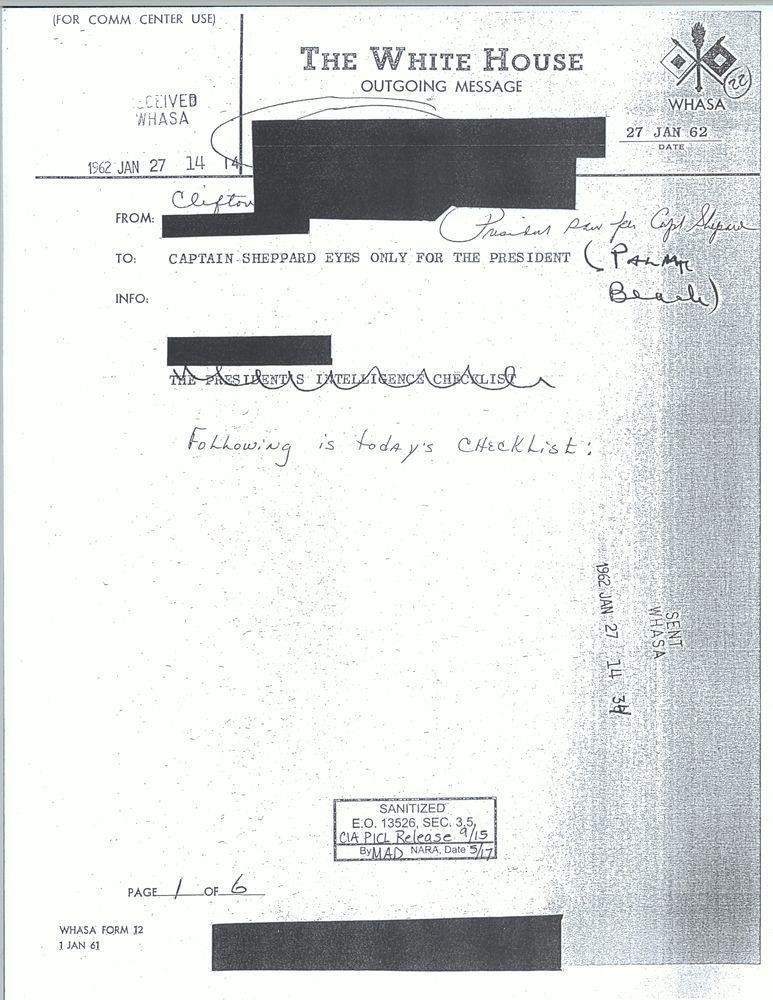

Because the PICLs were a near-daily dispatch, they followed the President wherever he traveled around the world. While he was away from the White House, the PICLs were wired to his location, and staff members often scribbled a quick note – “Palm Beach,” or “HP” for Hyannis Port, for example – to indicate where JFK was when he received the briefing.

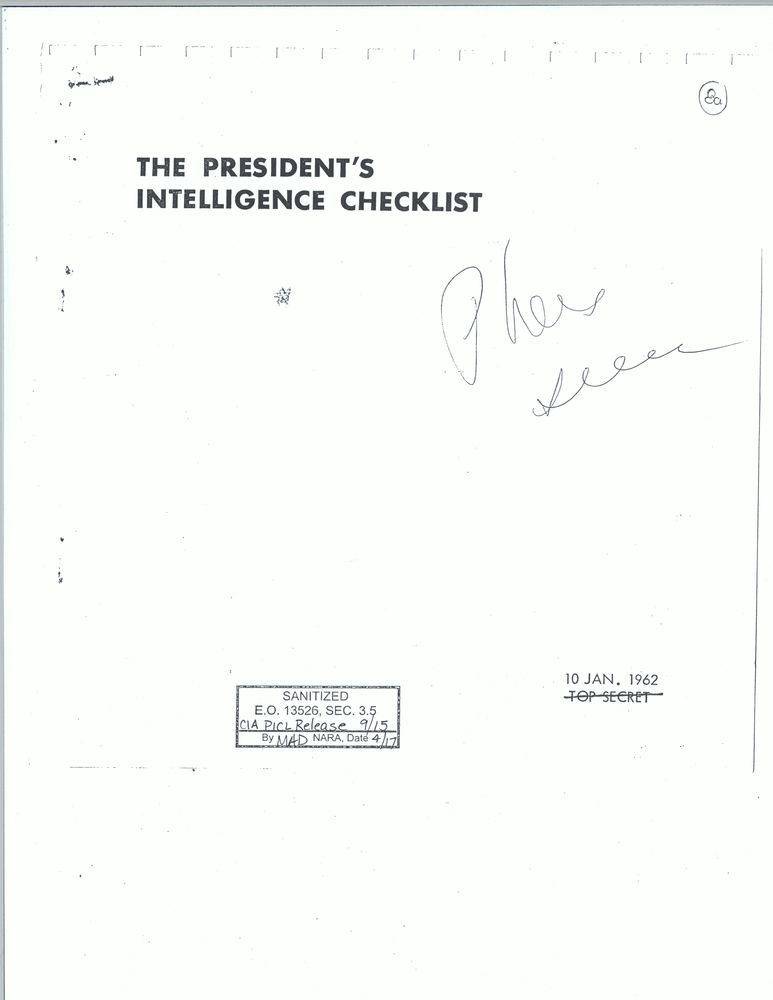

Though the PICLs are helpful for catching up on world events and even tracing the President’s whereabouts, historians find them especially useful for understanding the Administration’s priorities in foreign policy matters – and the wide range of global issues on the President’s mind at any given moment.

For example, the PICLs from late October 1962 often open with updates on the Cuban Missile Crisis – usually referred to as “the Cuban problem” – including details about missile locations and Soviet shipping operations. But the PICLs also reveal that the Cuban Missile Crisis wasn’t the Administration’s only international concern at the time. While much of the country focused on Cuba, the President and his team were also monitoring significant developments in the border conflict between India and China known as the Sino-Indian War; military activity in Vietnam and Laos; the relationship between Egypt and Yemen; requests for aid from the Congolese government; and other events unfolding throughout Latin America and Europe.

![5. USSR. The Soviets put what looked like a Mars probe into parking orbit yesterday, but we think it blew up when they tried to put it into trajectory. [Redacted]

6. India-China. a. The Chinese continue to attack and have overrun several more posts in both sectors. New Delhi says they are now within five miles of an important Indian base (Towang) in the northeast sector.

b. The offensive seems to have taken much of the starch out of the Indians. Foreign Secretary Desai told Ambassador Galbraith that India hopes to stabilize the front on ridges further south. From there, they plan to harass the Chinese during the winter and reclaim lost ground "in the months and years ahead."

c. Desai says India will need arms from us to do this and will be approaching us on the matter in the next few days. He says India does not expect much from the Soviets; "They have become cautious about Chinese feelings." Even Menon, he says, in unhappy about Soviet aid prospects.](https://jfk.blogs.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2022/06/JFKNSF-357-004-p0022.jpg)

![8. South Vietnam. a. South Vietnamese units have been alerted to the possibility that the Viet Cong may mount attacks on supply depots and main airfields this Friday, South Vietnam's national holiday. [Redacted.]

b. As often happens before a holiday, we have been getting a number of reports that the Viet Cong plan to step up terrorism for the occasion. In the past, such reports have not proved out too well.

c. This time, however, a concerted series of attacks would give a big boost to the Viet Cong campaign which in recent months have been confined to routine though widespread guerilla actions.

9. Congo. a. Adoula's government is again appealing to us for military assistance, arguing that unless bold steps are taken immediately to resolve the Katangan problem, Adoula will be overthrown by parliament when it reconvenes early next month.

b. Adoula will postpoine opening of parliament if he thinks it will oust him, but he will continue to use this argument and the "we will have to look elsewhere" refrain to press us for aid.](https://jfk.blogs.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2022/06/JFKNSF-357-004-p0024.jpg)

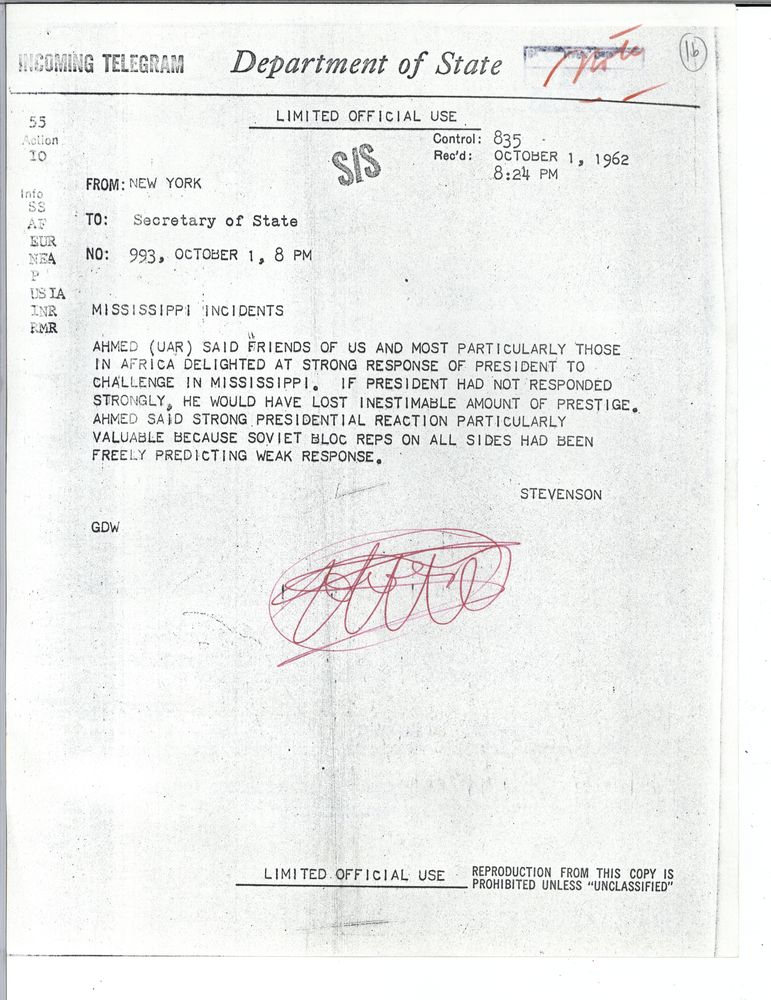

Occasionally, the PICLs also demonstrate how the President’s actions at home could reverberate on the world stage – especially on civil rights. Though some Kennedy Administration staff members (like Pedro Sanjuan) focused almost exclusively on the impact of domestic civil rights issues on international affairs, the PICL staff occasionally included updates on this topic, too. In early October 1962, one PICL relayed international responses to JFK’s actions to protect James Meredith from racist violence a few days earlier, when Meredith had arrived to enroll as the first Black student at the University of Mississippi.

The PICLs remained a constant presence through the rest of John F. Kennedy’s Presidency; in fact, the records show us that a PICL was among the last documents the President ever read. The PICL for the morning of Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963 carries a brief note stating that it was received at Fort Worth, Texas, and that the “President Read” it. Topics in this final Kennedy administration PICL include issues in the Soviet Union, Cambodia, Japan, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

![1963 Nov 22

From: Gen Clifton

To: Eyes Only for the President

Cite: CAP 63679

The President's Intelligence Checklist, 22 November 1963

Handwritten annotation #1:

Bromley Smith

Handwritten annotation #2:

President Read. [Illegible] rec'd Ft. Worth destroyed](https://jfk.blogs.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2022/06/JFKNSF-361-010-p0082.jpg)

As you browse the PICLs, you’ll likely notice a number of redactions, or blacked-out sections of text. These redactions represent information that is still considered too sensitive to release (for example, the names of local intelligence sources who have living descendants). You can learn more about declassification processes here, or contact JFK Library archivists at Kennedy.Library@nara.gov for details about submitting review requests for these items. As documents are further declassified through additional reviews, we’ll continue adding them to the digitized folders in the National Security Files.

You can find the complete run of the JFK Library’s PICLs in the digitized folders from Boxes 353 through 361 in the National Security Files finding aid, linked below.