By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

In 2015, archivists were working on preserving and updating descriptions of documents in the Ernest Hemingway Personal Papers at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library when we found something unexpected: two small, empty boxes that had originally stored Hemingway’s typewriter paper. The boxes (like a lot of Hemingway’s stuff) had been through a lot; they were stained, torn, and flattened, and they weren’t included in the collection’s most recent inventories.

Despite all this, it was easy to see why Hemingway saved them: he’d recycled these boxes to hold his book drafts while he worked on them. And true to a habit we see throughout his papers, he also used the boxes to jot down his handwritten notes, including daily word counts and background information, about two of the best-known works of his later career: The Old Man and the Sea and Islands in the Stream.

Processing archivists carefully rehoused and described the boxes in the updated collection guide, but knew that the boxes needed specialized conservation work and high-quality imaging to make them accessible to researchers. So we recently sent them, along with the last of Hemingway’s fishing logs, off to the conservation lab for treatment. We’re excited to share the results of the conservation work – and a little archival detective work of our own – with Hemingway fans and history nerds now!

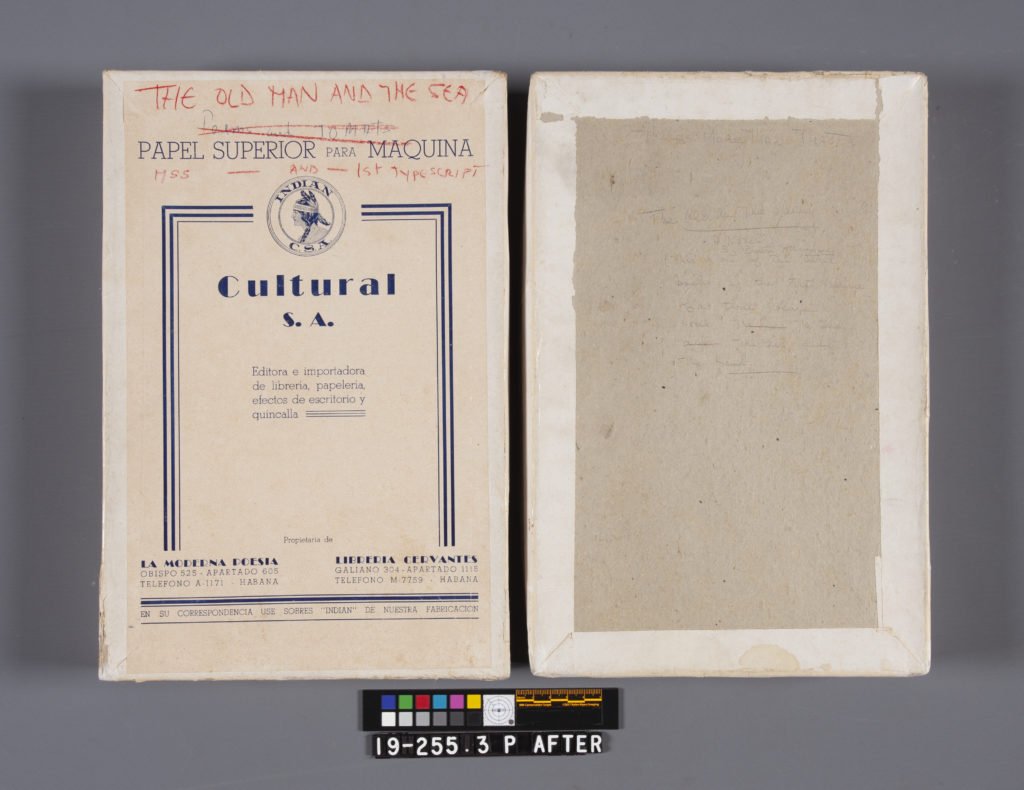

The Old Man and the Sea Box

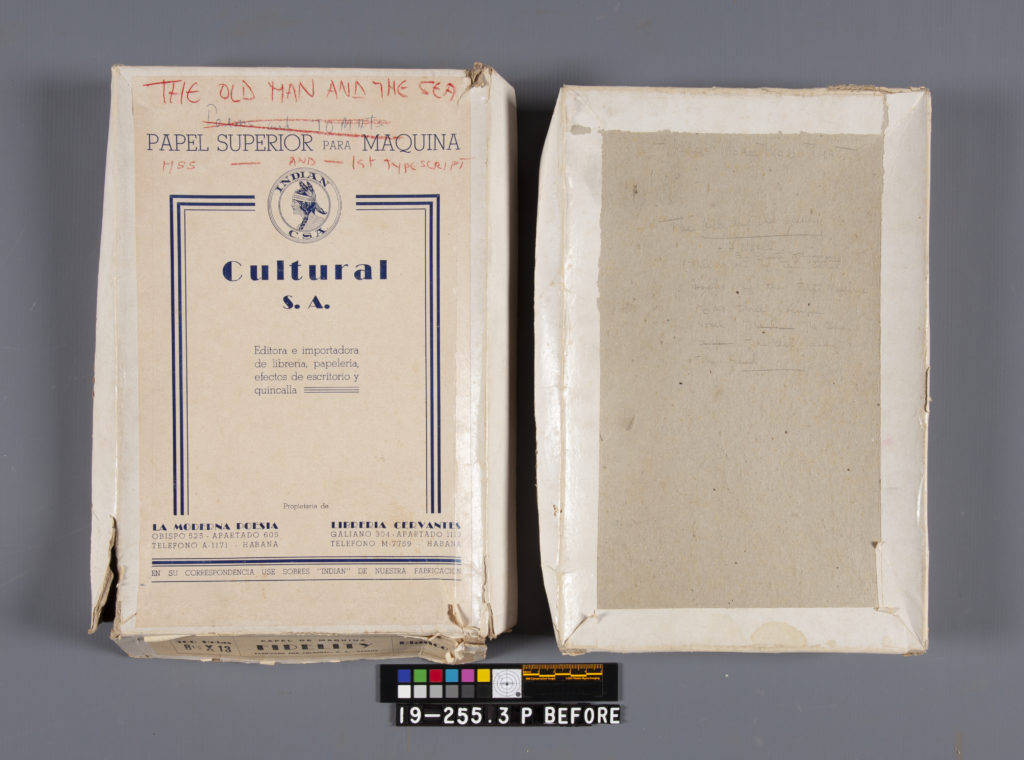

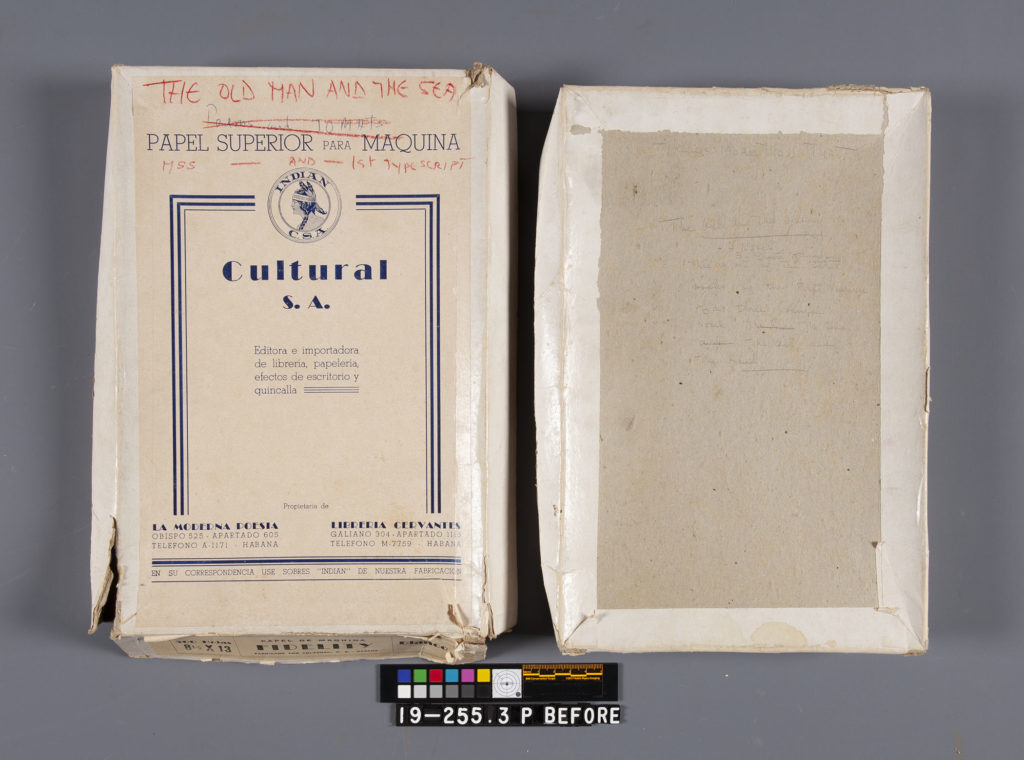

Though this box wasn’t listed in most of the past Hemingway collection guides, it was briefly mentioned in an early inventory of Hemingway’s papers, dating to 1969. From that inventory, we know that when the box first arrived at the JFK Library, it had two of Hemingway’s original drafts of The Old Man and the Sea inside: one was typed, triple-spaced and pencil corrected, clocking in at around 119 pages, while the other was a typed, 100-page, ink-corrected draft labeled “First typescript” by Ernest Hemingway’s wife, Mary.

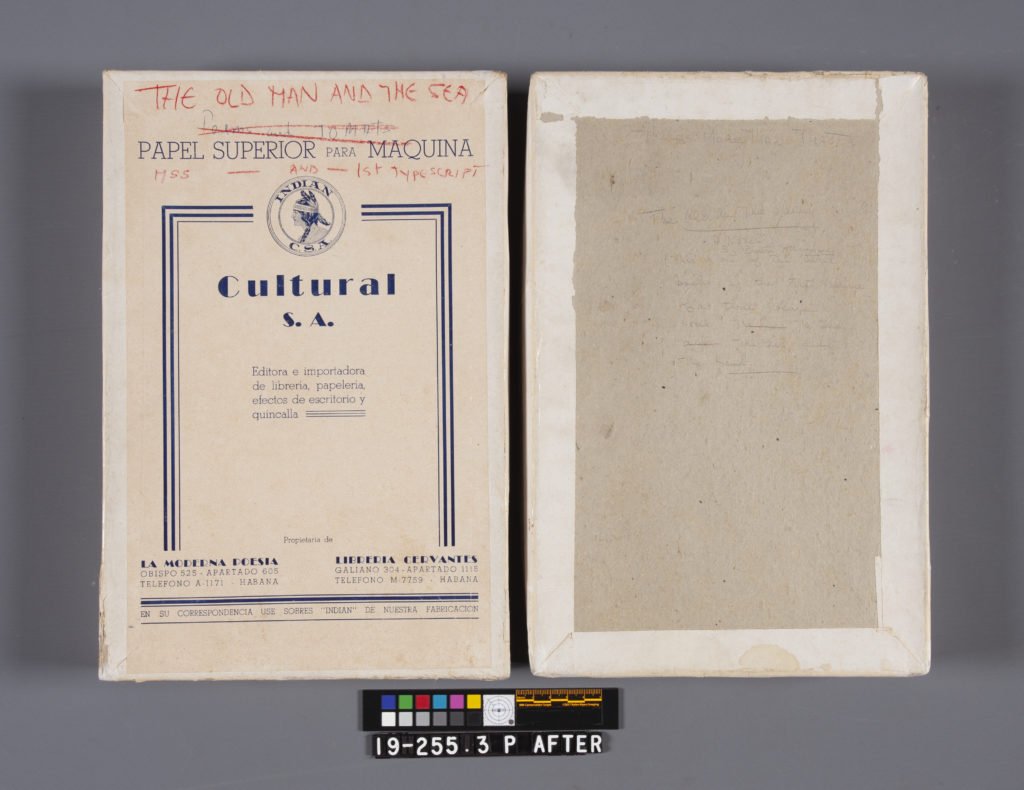

Mary Hemingway also wrote in red pencil on the box lid. She labeled it “The Old Man and the Sea” and included the note “MSS – AND – 1st TYPESCRIPT,” probably referring to handwritten drafts (known as manuscripts) along with a typed draft (commonly called a typescript). Meanwhile, Ernest Hemingway scribbled the faint graphite pencil notation on the bottom of the box, which reads:

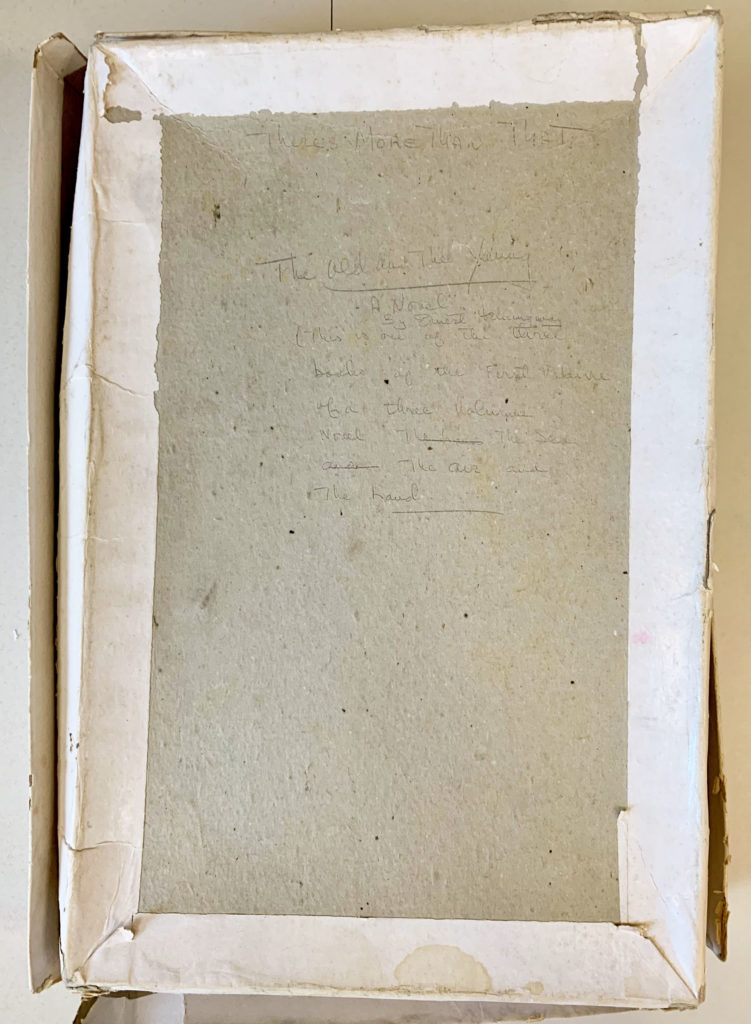

There’s More Than That

The Old and the Young

A Novel

By Ernest Hemingway

(This is one of the three books of the First Volume of a three volume novel

The LandThe SeaairThe Air and The Land.

Hemingway’s note tracks with what we know about the history of The Old Man and the Sea: that he originally wrote it to be part of a larger project he called The Sea, The Air, and The Land. Eventually, he decided to extract the story from that project and publish it on its own instead, debuting it in the September 1952 issue of LIFE magazine. But contrary to Mary Hemingway’s “MSS” note on the box, the archives only holds typescripts for The Old Man and the Sea – not handwritten manuscript drafts.

Her note could hint that handwritten drafts of The Old Man and the Sea once existed, but at least one researcher has speculated that the “MSS” note doesn’t refer to that novel at all, and could point instead to handwritten pages from other sections of Hemingway’s The Sea, The Air, and the Land project that were possibly housed in this box at one time, too (for more on that, see Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual, 1975).

Though the Hemingways’ notes turned this throw-away item into an archival object, the box wasn’t originally made to be kept forever. Constructed from fast-deteriorating materials like cardboard and adhesive, this box was stained and crushed, with its original shape distorted. Three of the sides were torn, and many areas were delaminating, flaking away in thin layers. And Ernest Hemingway made his notes in graphite pencil, which is especially likely to wear away over time.

At the conservation lab, dirt and fly specks (even flies leave their historical mark!) were cleaned off. Delaminating areas, broken edges, and other vulnerable surfaces were mended and filled, and the object was humidified and flattened over a form to recover its original shape. It was also photographed at high-resolution, so that researchers can examine the notes without damage to the original item. Now, the box is safely preserved and stored, and the information it holds is accessible for all.

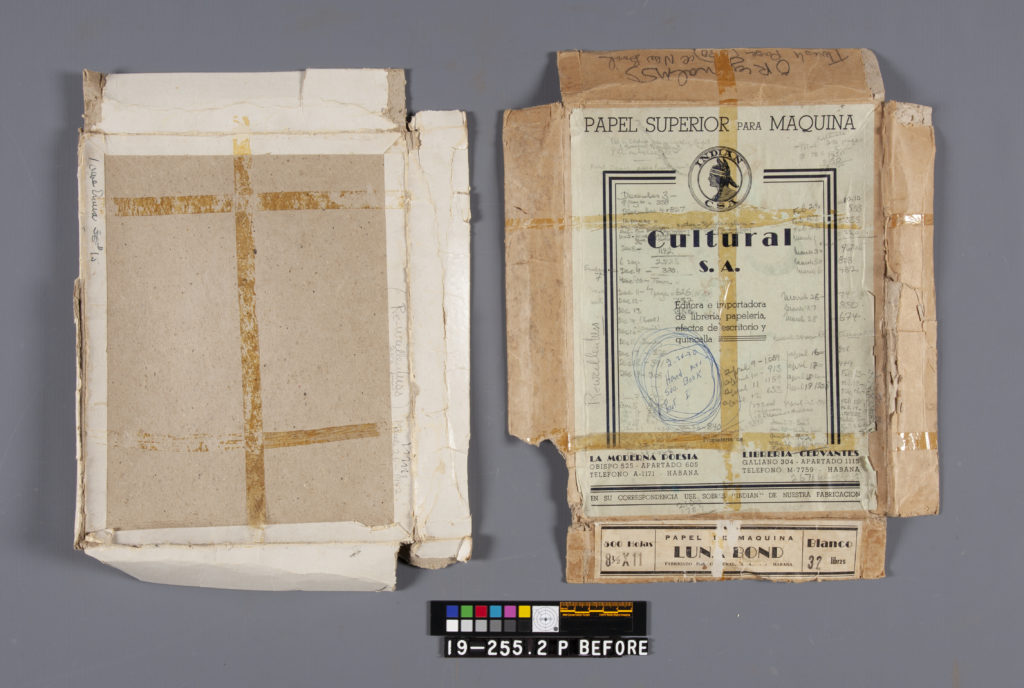

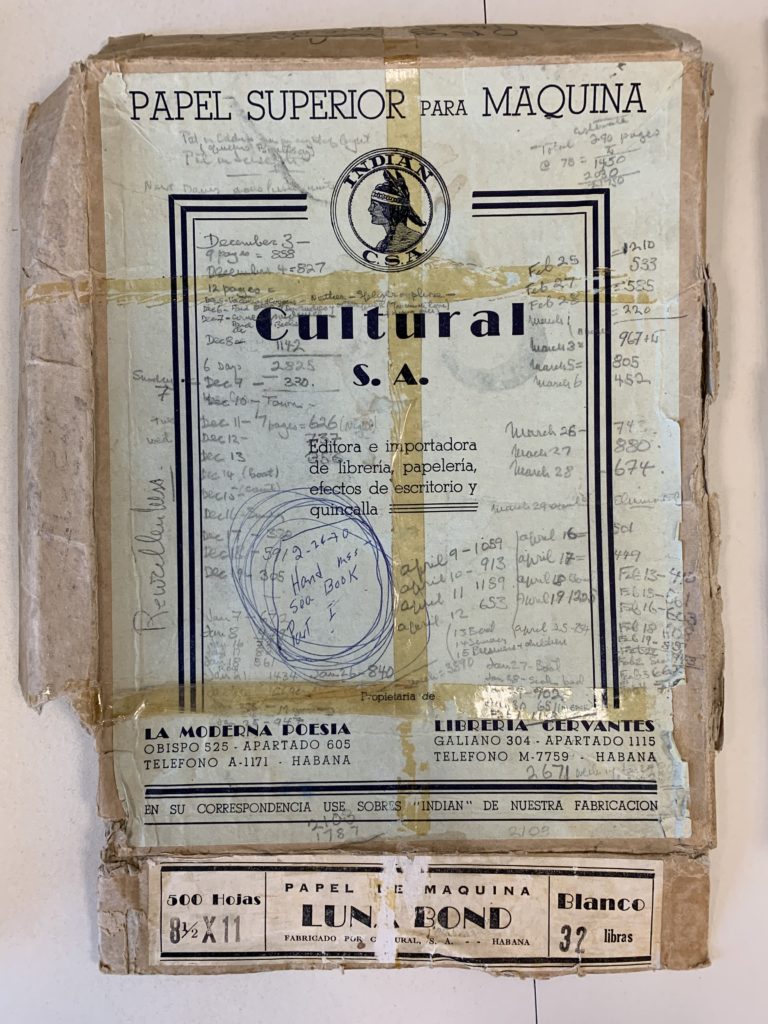

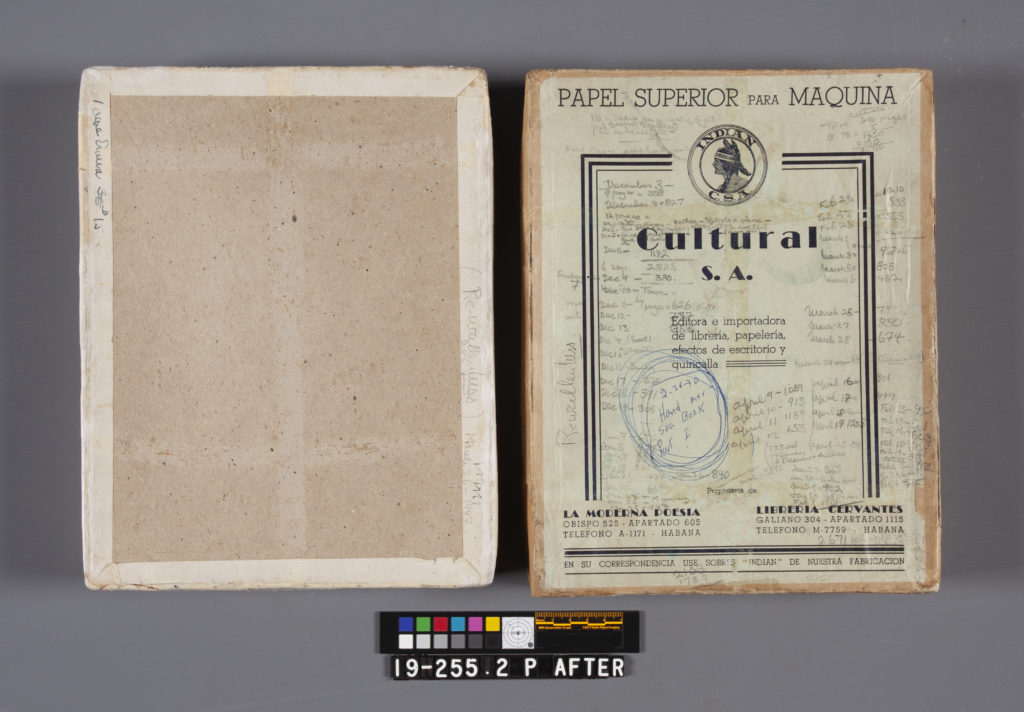

Islands in the Stream Box

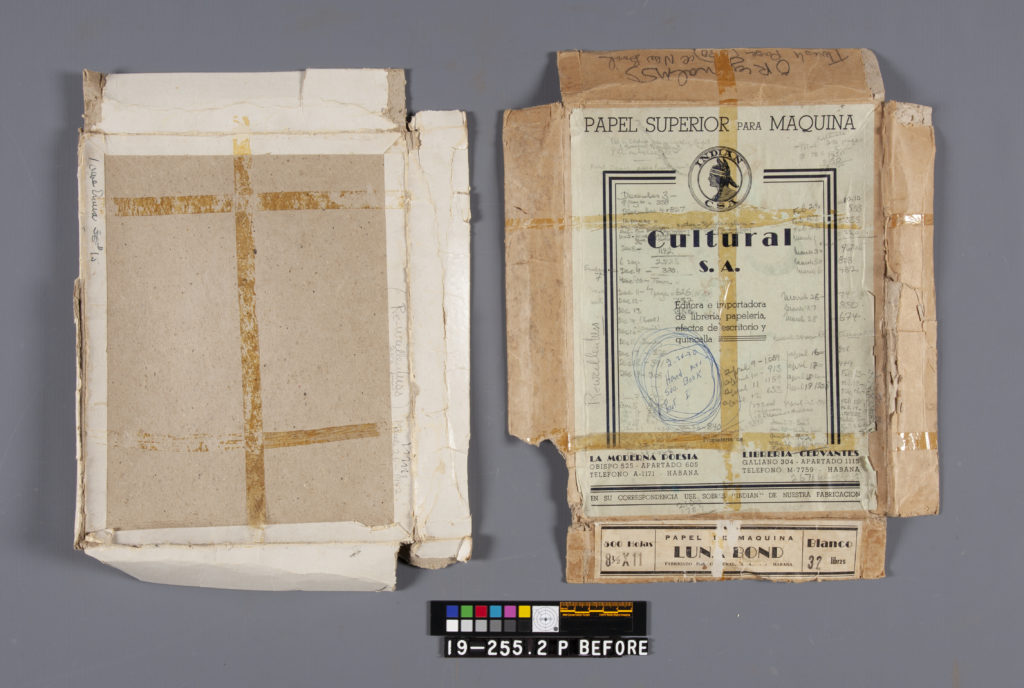

The second box relates to a project Ernest Hemingway worked on in the 1940s and early 1950s, edited and published after his death as Islands in the Stream (and yes, the song is named after the book!). As researchers have noted, Ernest Hemingway often referred to this project as “the sea novel,” which is echoed in his wife’s ink note on the front of the box: “Hand mss – Sea Book – Part I.” From a one-sentence mention in the 1969 inventory, we know that when the box arrived at the JFK Library, it had a draft inside: “Book One Chapter One” of the sea novel.

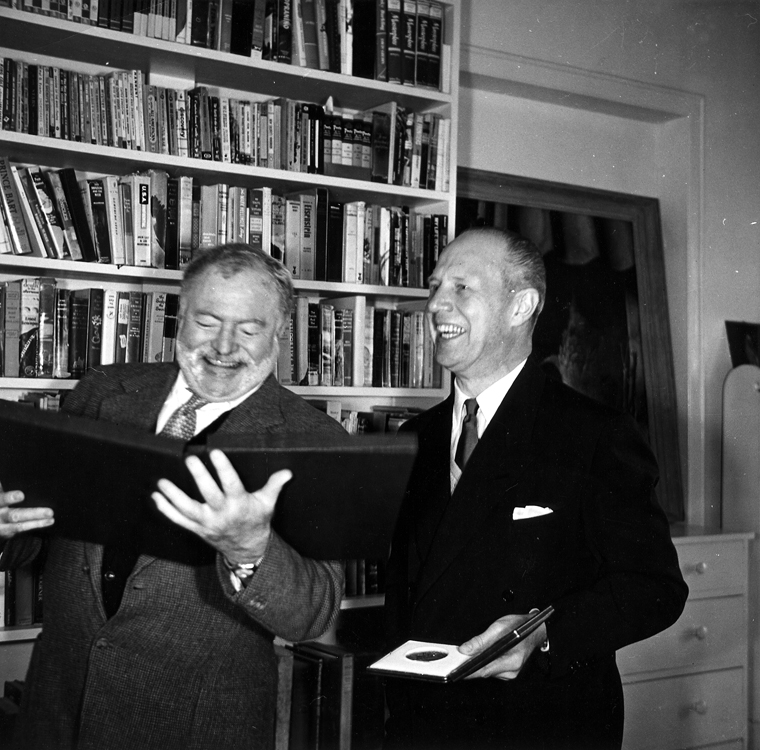

Though the work now known as Islands in the Stream wasn’t published before Hemingway’s death in 1961, it made its public debut at President John F. Kennedy’s 1962 White House dinner for Nobel Prize winners, where dinner guest Mary Hemingway watched as Frederic March read an edited excerpt from Hemingway’s drafts.

Much of the “Sea Book” box is covered in Ernest Hemingway’s handwritten daily word counts – a tactic he often used to document his writing progress. On the bottom of the box, Hemingway wrote “Rewritten Mss. March 26, 1947,” which the 1969 inventory noted “probably does not refer to” the draft that was inside the box when it arrived at the Library.

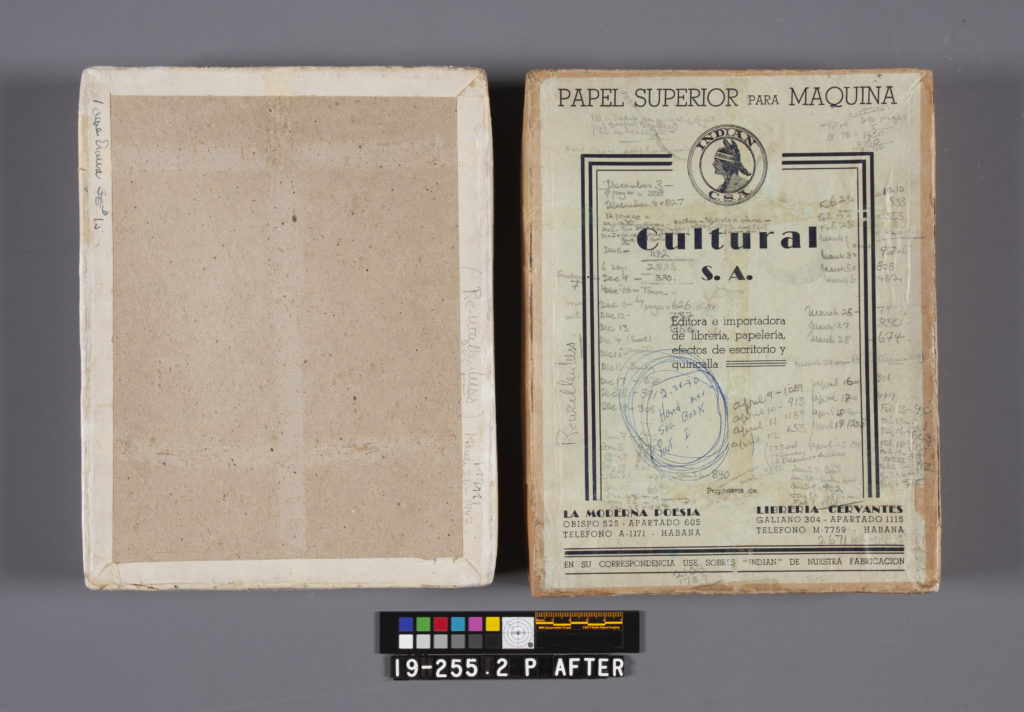

Like the The Old Man and the Sea box, the “Sea Book” box was highly worn, soiled, and crushed. The box had been torn at all four corners, and the green label paper on the top of the lid was peeling away from the cardboard. Making matters worse, three pieces of adhesive tape – the archivist’s nemesis – had been wrapped around the entire box, staining the label paper and damaging Hemingway’s handwritten graphite pencil notes.

At the lab, the box was cleaned and tears to the label paper and cardboard edges were repaired. The tape, residual adhesive, and staining were reduced as much as possible, and the box was humidified and flattened over a form to reshape it. Conservators built a custom container for safe long-term storage, and photographed the box at high-resolution to facilitate damage-free access to Hemingway’s notes.

All are welcome to visit the Library to explore the new high-quality facsimiles of these materials, or any of the other materials in the Ernest Hemingway Personal Papers or related Hemingway collections. Just email us at Kennedy.Library@nara.gov to learn more about making a research appointment, or check out the side-by-side before and after shots below!

With special thanks to the estate of Ernest Hemingway for granting permission to publish images of the boxes, and to the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation for funding the conservation of these materials.