By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

In the JFK Library’s archives, over 1,600 oral history interviews preserve stories from people who crossed paths with John F. Kennedy or Robert F. Kennedy, including dozens of Black activists, politicians, civil servants, journalists, artists, athletes, legal experts, and White House staff members. Between 1964 to the early 2000s, these interviews gathered insights from icons like Thurgood Marshall, James Baldwin, and John Lewis – and from Black Americans who are harder to find in history books, including Marjorie McKenzie Lawson, Preston Bruce, Robert Weaver, and Ruth Batson.

Archivists and historians have written about the ways oral histories can be flawed, especially when they’re collected by governments: some interviewers ask more informed (or biased) questions than others, and some interviewees from marginalized communities don’t feel comfortable or safe sharing their full stories. But when they’re read with these limitations in mind, oral history interviews can help expand the historical record with the stories of people who are often left out of it. Here, we’re spotlighting some interviews from our collections, by both famous and lesser-known Black Americans.

Content note: most interviews were conducted by former Kennedy administration members and early JFK Library staff, and in some cases, by author Jean Stein. Some interviewers and interviewees used now-outdated terms to refer to minority groups. Additionally, some interviewees shared graphic descriptions of their experiences with anti-Black racism, terminology, and violence. Their language has been retained in the transcripts.

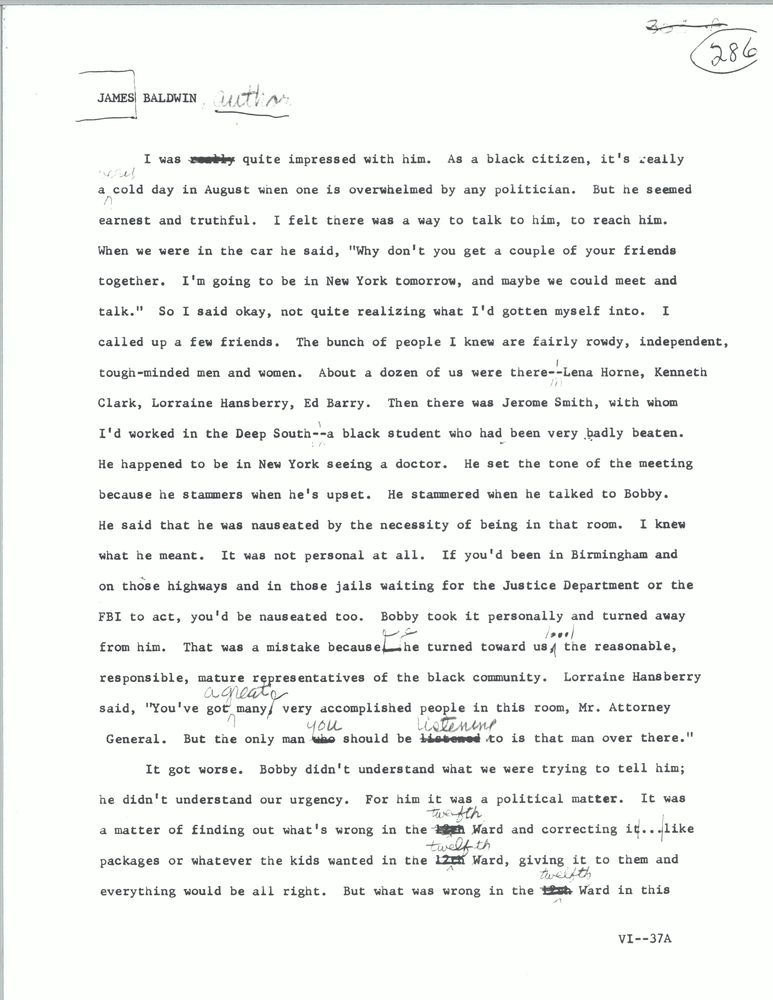

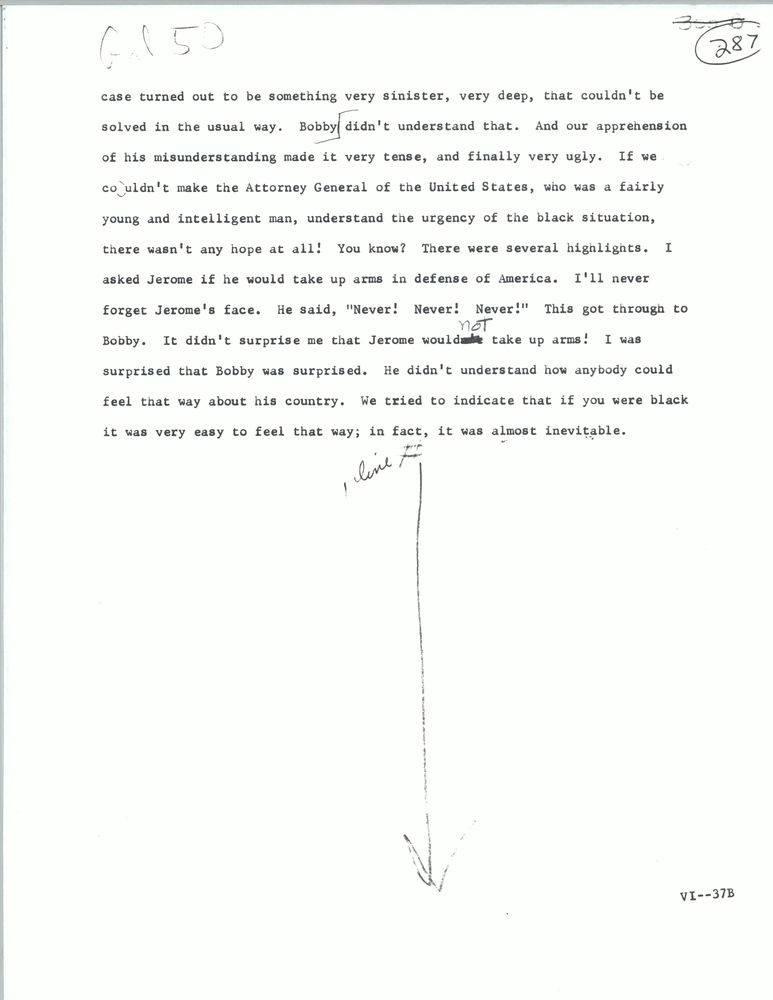

James Baldwin

In May 1963, writer James Baldwin and other Black artists and civil rights activists were asked to meet with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who Baldwin felt “didn’t understand our urgency. He didn’t understand what we were trying to tell him.” In his interview, Baldwin recalled the now-famous meeting and shared his thoughts on 1960s civil rights protests: “While people are being murdered, you can’t scare them by threatening to murder them. What you do is create a resistance that you can’t control! This has always been true throughout history.”

Baldwin’s interview was conducted by author Jean Stein in 1970 as she worked on a book about Robert F. Kennedy; read Baldwin’s full interview in the Jean Stein Personal Papers here, and learn more about his role in Black and LGTBQ+ activism here.

Marjorie McKenzie Lawson

Social worker and attorney Marjorie McKenzie Lawson was an advisor to JFK in the Senate before becoming Civil Rights Division Director in his 1960 Presidential campaign. In her 1965 interview with JFK Library archivist Ronald Grele, Lawson discussed her years of networking in Black communities and disputed a popular historical narrative: that the Kennedy campaign won over the majority of Black voters just weeks before the election, when JFK called Coretta Scott King after Martin Luther King, Jr. was arrested in Georgia. Lawson argued that the journalists and campaign staff who credited the phone call (and its publicity) for Kennedy’s success with Black voters erased years of on-the-ground labor by Black politicians, campaign workers, and activists:

What about all of the years of work that Congressman [William] Dawson had done to build Negro strength in the Democratic party? …He had well-organized groups of Negro voters all over the country. We built on that.

We built on the years that I had toured around the country – all of the correspondence; all the telephone conversations; all of the meetings… Here were years of concentrated effort. For the first time, a candidate had made a staff and funds available in recognition of Negro voters and had helped them organize and get out the vote. Were we to say that Negroes were so childlike and so unsophisticated that they cared nothing for the organizational work that had been done and the recognition that they had received but had responded to one telephone call and had rushed then to the polls and voted for Senator Kennedy? …It was a great disservice to the people who had worked so hard in the campaign both nationally and locally.

Marjorie McKenzie Lawson, Oral History Interview JFK #2, 11/14/1965, page 40.

Lawson also talked about her role as a judge in Washington and the challenges of working in politics as a Black woman. Learn more in her first oral history interview here and her second interview here.

Preston Bruce

As the White House Doorman through five Presidencies (from Eisenhower to Ford), Preston Bruce played a role in some iconic moments in Presidential history. In his 1964 interview, he remembered helping John F. Kennedy and other global leaders navigate state dinners, and working long hours with Jacqueline Kennedy in the days after the President’s assassination.

Bruce’s interviewers, Nancy Tuckerman and Pamela Turnure, were members of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s staff, and focused their questions on his impressions of the Kennedy family. They didn’t directly ask Bruce about his life or issues related to the Black community, but glimpses of his own story come through in his mentions of his late working hours, his economic status, and his son’s attendance as the only Black student at his university in Vermont. Read his oral history interview here, and find more images of Bruce in the digital archives here.

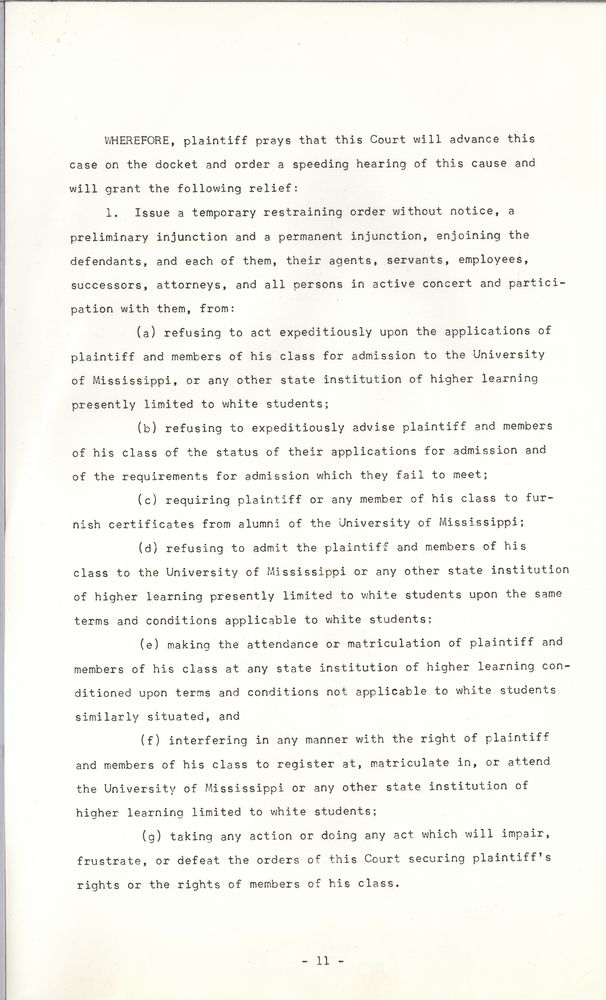

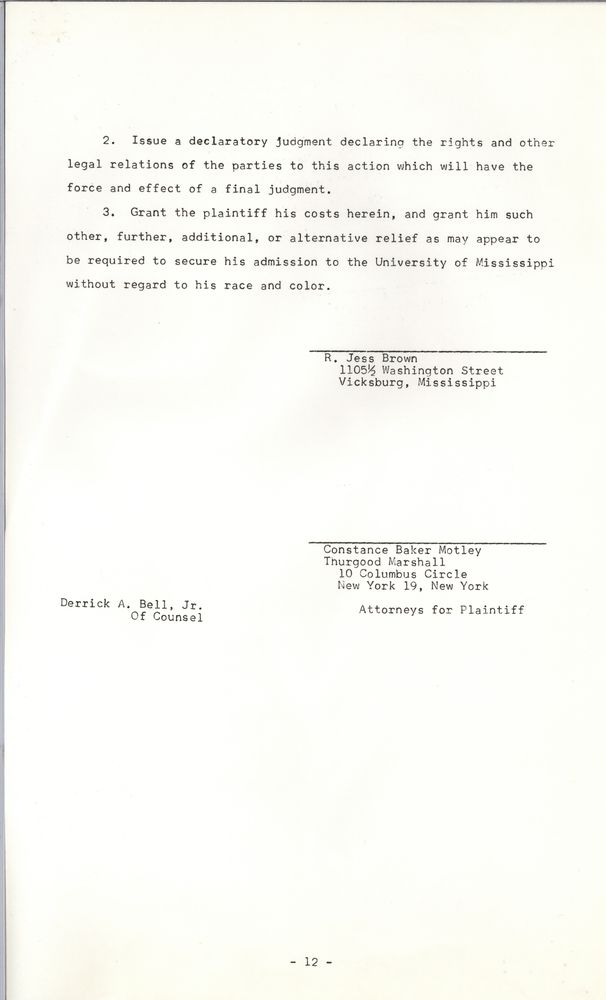

Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall was confirmed as a Supreme Court Justice in 1967, but when he was interviewed in 1965, he was still a federal judge in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals – a position he was nominated for in 1961 after he helped James Meredith integrate the University of Mississippi. In his interview with Berl Bernhard (the Kennedy administration’s Staff Director for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights), Marshall recalled his experience as an attorney and Director of the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund; described the “long siege” of Congress’s delay in confirming his appeals court nomination; and shared his opinions of JFK, RFK, and their actions on civil rights. Read his interview here, and find more about his confirmation battle here.

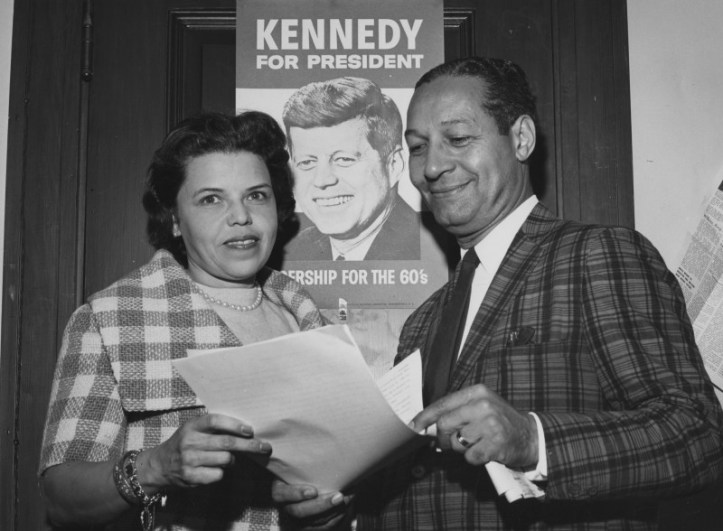

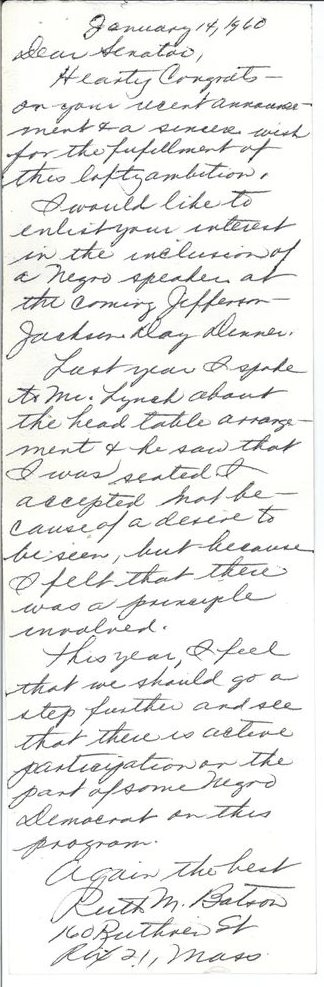

Ruth Batson

Ruth Batson was the first woman elected President of the NAACP’s New England Regional Conference. As an expert in educational discrimination and structural racism, Batson fought public school segregation in her hometown of Boston and called for including Black leaders in the Democratic Party. In her 1979 interview with JFK Library Historian Sheldon Stern, Batson discussed her own activism and her work on JFK’s Senate campaigns, describing how she and her NAACP colleagues came to feel that “civil rights was not one of Kennedy’s high points.” Read her interview here and some of her letters to Kennedy in the archives here, and learn more about Batson’s work to desegregate Boston schools here.

Robert Weaver

Economist Robert Weaver had served as Chair of the NAACP’s board, worked with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and advised the cities of Chicago, New York, and Washington D.C. on housing issues before he was appointed as Administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency (HHFA) in 1961. In his five interviews with then-Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Weaver discussed his work at the Agency and the impact of racism on housing – and on his own lengthy Congressional confirmation process as HHFA Administrator:

The fact that from the point of view of a human being, because I was a Negro, regardless of my qualifications, my capabilities or anything else, I was subjected to this long hearing – much of it irrelevant, much of it without any basis of fact – was demeaning. …I felt that this was, again, an evidence of the fact that Negroes in America are still not first class citizens.

…You know, I didn’t become a Negro yesterday, and I didn’t become a Negro the day of that appointment. I had had a lot of experiences. I had had a lot of situations. So this wasn’t new to me.

Robert Weaver, Oral History Interview JFK #1, pages 59-60.

Weaver also recalled the Kennedy’s administration’s unsuccessful attempt to create a new Cabinet-level “Department of Urban Affairs and Housing,” and the rumor that Weaver was the top candidate to be appointed its Secretary. Though the Department now best known as HUD (Housing and Urban Development) still didn’t exist by the time Weaver was interviewed in 1964, Congress passed legislation to create it in 1965 – and confirmed Weaver as its Secretary, making him the first Black Presidential Cabinet member in American history. Read all of Weaver’s interviews online: JFK Interview #1 | JFK Interview #2 | JFK Interview #3 | JFK Interview #4 | JFK Interview #5.

John Lewis

When John Lewis was interviewed by historian Vicki Daitch in 2004, he’d been serving as a U.S. Congressional Representative for Georgia for almost 20 years. In his interview, he reflected on his early civil rights activism for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), including his roles in the Freedom Rides of 1961 and the March on Washington in 1963. Lewis described the racism and violence he faced over years of participating in these protests, particularly in the 1965 march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

Lewis also shared his thoughts on the Kennedy administration, fellow civil rights leaders, and the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement. Read or listen to his interview here, and learn more about his life and work here.

The interviews and documents highlighted here represent only a small number of the records that carry Black voices in the archives; thousands of Black Americans wrote letters to the President, testified in federal civil rights cases, and worked for or engaged with the government in ways that have led to the preservation of their experiences in the JFK Library’s archives. The oral history interviews collected through the JFK Library add to these first-hand accounts, helping to fill in gaps in the narratives about American history.

Even more interviews can be found in the John F. Kennedy Oral History Collection, the Robert F. Kennedy Oral History Collection, and the Jean Stein Personal Papers; click the links to browse those collections (including listings of interviews that haven’t been digitized yet), or read more oral histories by Black Americans online below:

- Ralph Abernathy, Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) leader: Stein Interview #1

- Harry Belafonte, entertainer and activist: JFK Interview #1 [copyrighted; contact Reference staff for access]

- Simeon Booker, journalist: JFK Interview #1

- Isaac Coggs, politician: JFK Interview #1

- James Farmer, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) leader: JFK Interview #1 | JFK Interview #2

- Earl Graves, Sr., RFK assistant, publisher, and businessman: RFK Interview #1 | RFK Interview #2 |RFK Interview #3 |RFK Interview #4 |RFK Interview #5 |RFK Interview #6 |RFK Interview #7 | Stein Interview #1

- Roosevelt “Rosey” Grier, athlete, entertainer, and activist: Stein Interview #1

- Andrew Hatcher, Associate White House Press Secretary: JFK Interview #1

- Aaron Henry, NAACP leader: JFK Interview #1 | JFK Interview #2

- Wilma Holness, White House maid: JFK Interview #1

- Martin Luther King, Jr., SCLC leader: JFK Interview #1 [copyrighted; contact Reference staff for access]

- Belford Lawson, Jr., attorney, activist, and campaign advisor: JFK Interview #1

- Louis Martin, journalist and Presidential advisor: JFK Interview #1 | JFK Interview #2 | JFK Interview #3

- Booker T. McGraw, Assistant to the HHFA Administrator: JFK Interview #1

- Clarence Mitchell, NAACP leader: JFK Interview #1 | JFK Interview #2

- Frank Reeves, activist and Presidential assistant: JFK Interview #1

- George H. Taylor, valet to John F. Kennedy: JFK Interview #1 | JFK Interview #2

- Herbert Tucker, attorney, NAACP leader, and Senate office/campaign worker: JFK Interview #1

- Roy Wilkins, NAACP leader: JFK Interview #1

Thank you for this post – I so appreciated it! I’m a graduate student in American History researching the role that Marjorie McKenzie Lawson played in shaping the Kennedy campaign’s approach to civil rights and politics around race relations. In Lawson’s oral history, she alluded to writing “memoranda on race relations” and the interviewer, Grele, says, “the Library would like to have those files.”

The citation for the oral history is:

Marjorie McKenzie Lawson, recorded interview by Ronald J. Grele, October 25, 1965,(page 3), John F. Kennedy Library Oral History Program.

“GRELE: The Library would like to have those files.

LAWSON: Maybe I’ll be able to put some of the things together for

you, some of the memoranda that I wrote on race relations.

GRELE: It would make a good collection for the Library.

LAWSON: There may even be a book in it. No from me, though, I’m

not going to write a book.”

I’m curious as to whether those files were ever given to the Archives. I would love to have access to them, and would appreciate any support you can offer. I look forward to hearing from you.

Hi Evan – thanks for reading! We’ll look into your questions and will be in touch via email.

[…] to PresidentsHoover Heads: Desegregating the Commerce DepartmentJFK Library Archives: “Understand Our Urgency:” Oral Histories by Black AmericansJFK Library Archives: Making the March on Washington, August 28, 1963National Archives […]