By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

Though President John F. Kennedy didn’t appoint any people known to be of Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) heritage to his Cabinet or other senior Administration positions, the achievements, struggles, and experiences of many AAPI people around the country – and inside the government – can still be found documented in the JFK Library’s archives. For this year’s AAPI Heritage Month, we’ve been spotlighting some of their stories (and you can check out earlier posts here and here). This week, we’re focusing on the work of an AAPI “hidden figure” in the U.S. government: interpreter Yukio Kawamoto, whose expertise in the Japanese language played a role in shaping 20th-century history.

In 1942, Yukio Kawamoto was in his early 20s and a student at the University of California when he was drafted into the United States Army. Two months later, his parents, Kumajiro and Chisato Kawamoto, were imprisoned with 120,000 other Japanese Americans in the federal government’s internment camp system. While the government was forcibly relocating Kawamoto’s parents – immigrants who’d passed their Japanese fluency on to their American-born son – the Army was testing his language skills, eventually sending him to the Pacific as an interpreter for combat units stationed there. Kawamoto translated intercepted documents and communicated with war prisoners, producing intelligence that guided the American military’s strategy in the region. When he was awarded a Congressional Gold Medal in 2011 for his World War II service, he told the Washington Post what it was like to spend his military leave visiting his parents in an internment camp bunker at Camp Topaz, Utah:

I wasn’t happy about it…They were there for the duration of the war, while I was out fighting for the United States. But what could you do?

Kawamoto to the Washington Post, 7 December 2011

After his war service, Kawamoto helped with the relocation of Japanese Americans who’d been imprisoned in the camps. He soon started working as an interpreter in the U.S. State Department, later saying: “I wanted to get into the State Department, and the main reason was to promote better relations between Japan and the United States.” In Washington, Kawamoto was the State Department’s only Japanese language interpreter, and he facilitated conversations between Japanese visitors and the press, government and nonprofit organizations, and Presidents – including President John F. Kennedy.

Like many federal workers who were also members of American minority communities, Kawamoto and his contributions can be hard to find in U.S. history books. But his work is documented in the archives at the JFK Library, and with a little searching, we can see glimpses of his role in historical events.

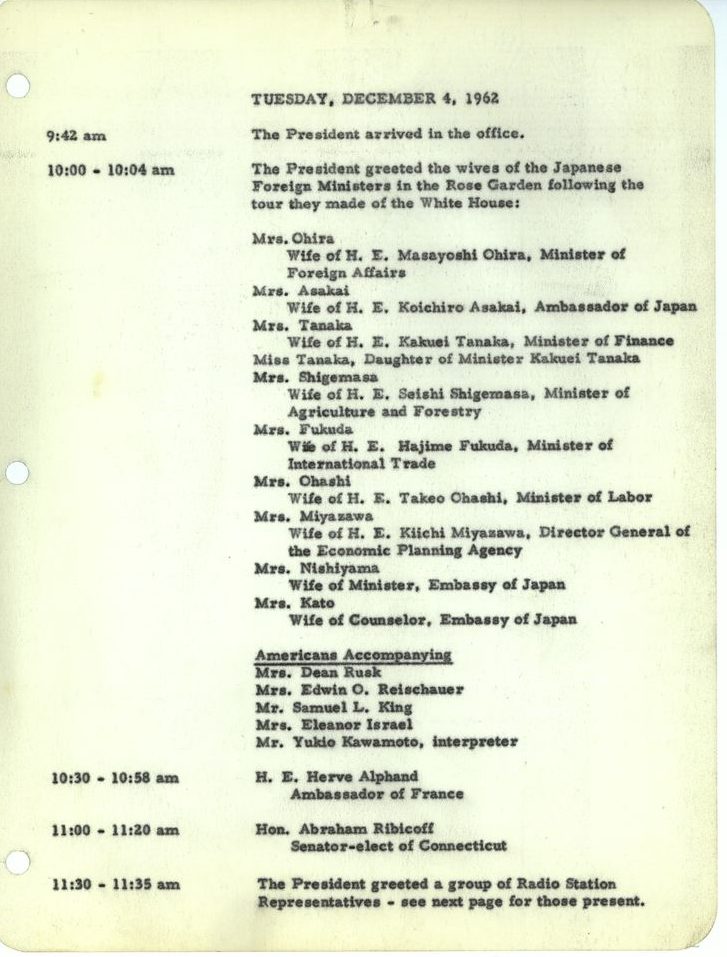

In the President’s Appointment Book for December 5, 1962, Kawamoto appears in a list of “Americans accompanying” the spouses of Japanese Cabinet members and diplomatic officers as they toured the White House and met briefly with the President. Knowing that Kawamoto was there, we can keep an eye out for him while looking through the White House photographs taken during this meeting – and spot him at the President’s side as they talked with the visitors.

Kawamoto translated for this group and their larger party of U.S. and Japanese officials, spouses, and press corps members – who had gathered in Washington for the Joint U.S.-Japan Committee on Trade and Economic Affairs – as they toured the Washington area. To promote the exchange of Japanese and American cultures, the group visited Colonial Williamsburg and other heritage sites, and even attended a fashion show. The Associated Press reported that Kawamoto earned the group’s praise when, for the first time in his many years of translating for the U.S. government, he “found himself explaining a variety of American fashions, from a pink old-fashioned night gown in brushed orlon to a bridal costume.”

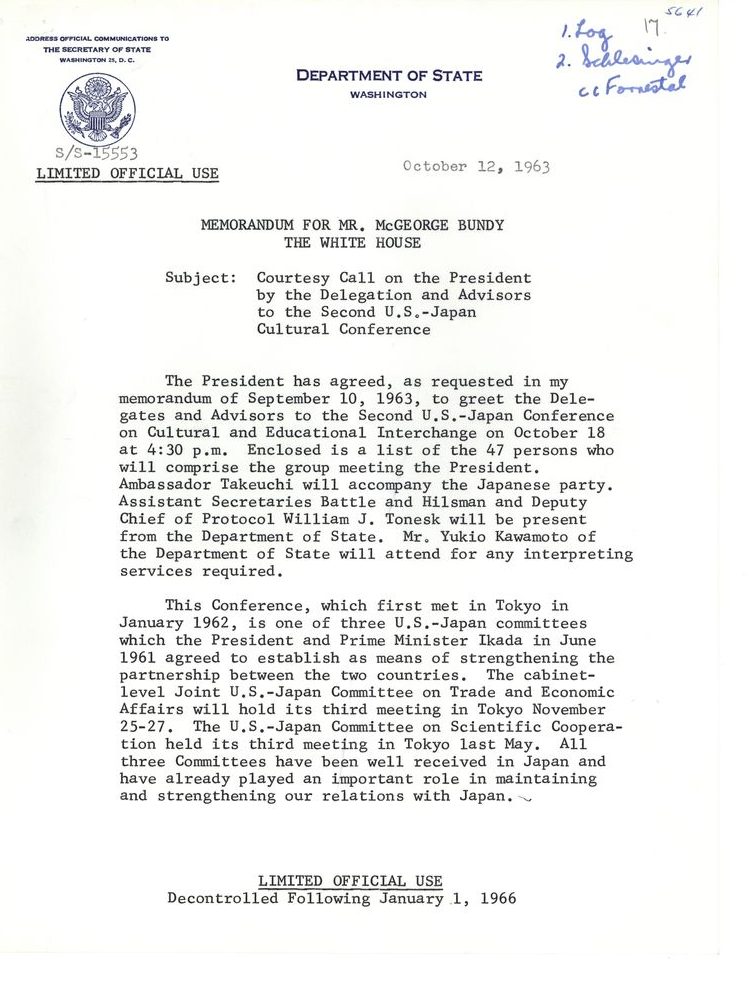

Kawamoto’s interpretive service also comes up in documents about a meeting on October 18, 1963 between the President and the U.S.-Japan Cultural Conference, which “played an important role in maintaining and strengthening our relations with Japan.”

Finding documentary evidence that Kawamoto interpreted this meeting makes it easier to track down photographs he might appear in. In one archival photograph of the event, we can find him working at the President’s right hand as he spoke with Conference delegates at the White House.

Kawamoto continued to work for the State Department in Washington until 1975, when he moved to Tokyo to serve as an interpreter at the U.S. Embassy. He retired from federal service in 1979, and later reflected on observations from his lifetime of facilitating communication between Japan and the United States: “I think a lot of the trouble we have in the world is through sheer ignorance. …I think that we should make every effort to understand different peoples and different cultures, and develop understanding between these countries to maintain the best of relations.”

Like many communities that are underrepresented in narratives about American history, the AAPI community’s stories are often underrepresented in archives, too. But sometimes, glimpses into historical AAPI lives can be “hidden in plain sight”: AAPI stories might be recorded, photographed, or written down in archives related to historical events – but not mentioned in the history books about those events. In the JFK Library’s archives, we’re committed to preserving the records that can shine a light on the ways that Yukio Kawamoto and other AAPI people have shaped history.

You can learn more about Yukio Kawamoto’s life, World War II experience, and career through the United States Department of Veterans Affairs and Kawamoto’s oral history interviews with the Library of Congress Veterans’ History Project and the National World War II Museum.

How nice. How about linking this with his “private” letters to and from the Japanese captain who smashed his PT boat? Did he invite the guy to the White House? Jack’s reaching out in forgiveness—what an act of amity and unity. Happy 103rd birthday, Jack.

You should take part in a contest for one of the best blogs on the web. I will recommend this site!