(A version of this post was published on our previous blog on 7/3/2014; we’ve republished it in honor of Black History Month.)

By Elyse (Edwards) Fox, Former Graduate Student Intern (Simmons College GSLIS) and Archivist for Textual and Photographic Digitization

On June 11, 1963—the day two African American students were admitted to the University of Alabama despite being physically blocked by Governor George Wallace—President John F. Kennedy addressed the nation on civil rights. In his speech the President implored all Americans to help promote the ideals of equality on which our nation was founded and announced his plans to submit to Congress civil rights legislation to institutionalize equality for all.

Listen to the June 11, 1963 address.

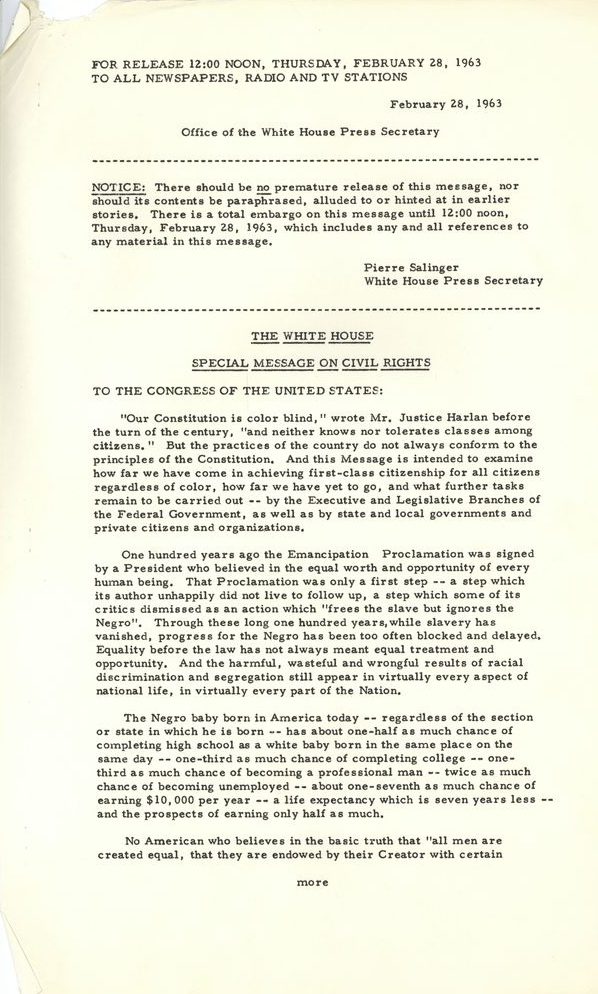

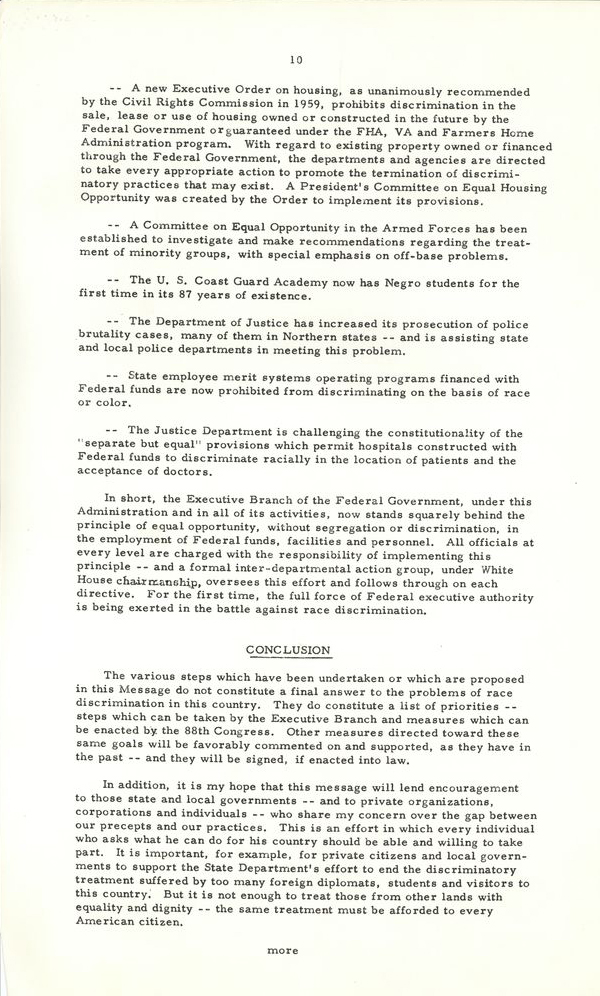

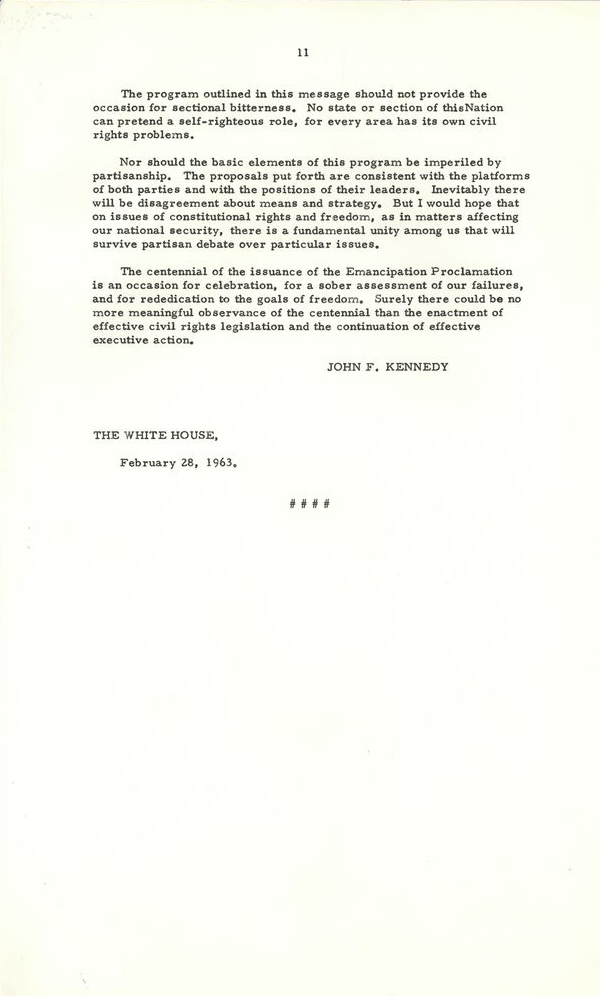

By 1963 most states in this country had integrated businesses, schools, and public spaces, but integration proved much more difficult in southern states where policies and attitudes were still highly discriminatory. In his address to Congress on February 28, 1963 President Kennedy asserted that we must fight for the liberty of all Americans, “…above all, because it is right.” On June 19, 1963 President Kennedy submitted to Congress the Civil Rights Act of 1963, intended to resolve weaknesses of previous civil rights legislation that lacked enforcement provisions. The bill would allow the Attorney General to file lawsuits against those who sought to deprive individuals of rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution or by law. The legislation also addressed inequalities and grievances on issues of voting rights, public accommodations, and desegregation of public schools; it established the Community Relations Service, authorized the continuation of the Civil Rights Commission, prohibited discrimination in federally-assisted programs, and established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Unfortunately, President Kennedy was not able to pass the legislation during his time in office. However, President Lyndon B. Johnson continued the fight and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (H.R. 7152) was officially signed into law on July 2, 1964. The passage of this act was the culmination of years of hard work by President John F. Kennedy, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Burke Marshall, and countless others. While this period in our nation’s history saw many acts of violence and oppression perpetrated against civil rights activists and civilians alike, the Civil Rights Movement ultimately saw success in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

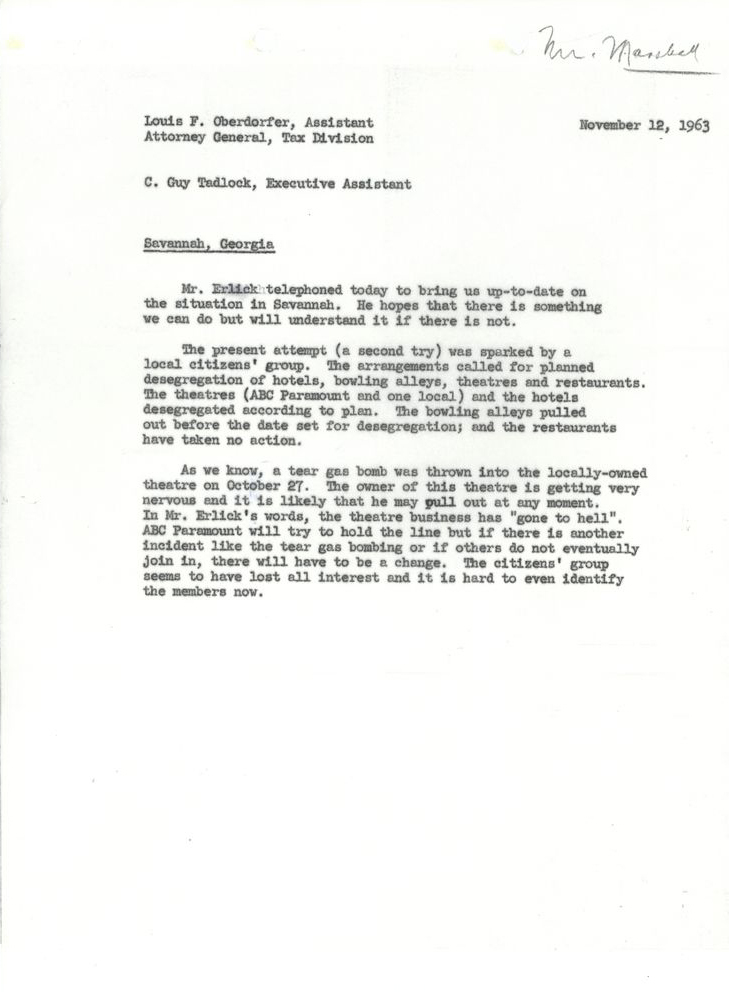

Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall played an instrumental role in advancing the goals of the Civil Rights Movement within the federal government and beyond. Never one to shy away from fighting the hard fight, his work in negotiating with parties on both sides of the movement helped stabilize the country as it moved toward integration. Documents throughout the Burke Marshall Personal Papers illustrate in vivid detail the necessity for the passage of a civil rights bill.

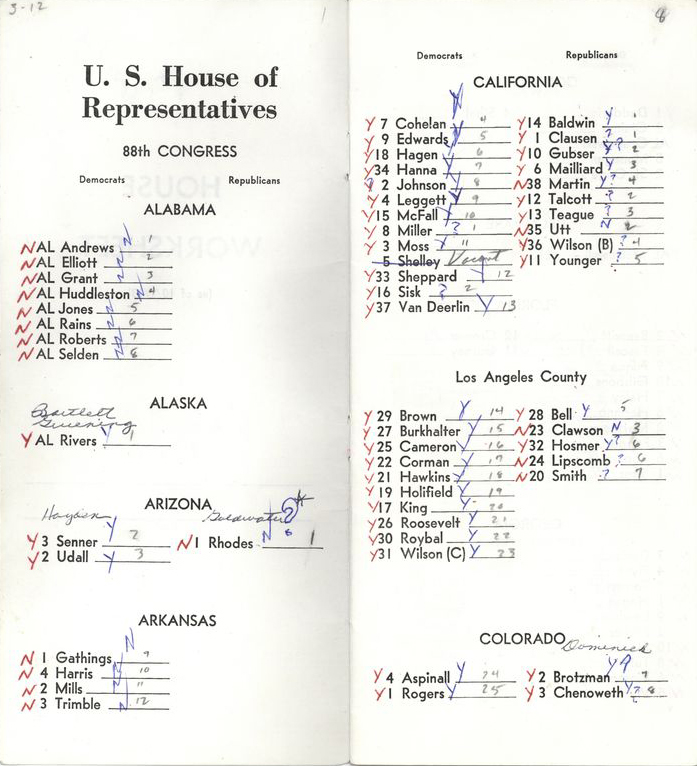

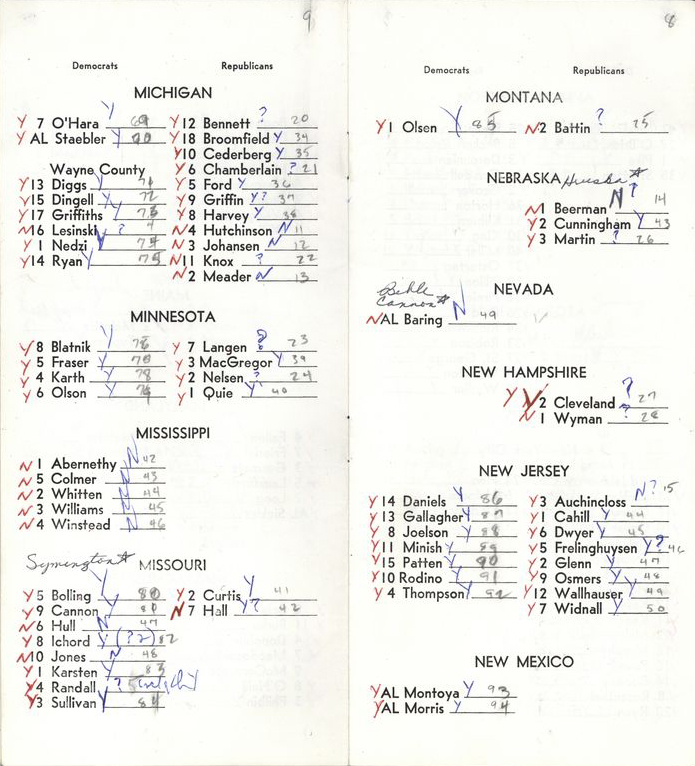

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 series within the Burke Marshall Personal Papers documents major components of the bill and summarizes the necessity for each of its titles, as well as its provisions and precedence. In addition, the series addresses criticisms and arguments from those opposed to the bill. These documents showcase the evolution of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 during the months of debate in the House of Representatives and the Senate. Highlights of the bill are as follows:

Title I: A mandate for the equal application of voter registration requirements. Literacy tests and oral or written interpretations of state and federal constitutions were consistently used to prevent eligible African Americans from voting. While these literacy tests were not completely eliminated with the 1964 Act, the bill mandated that they be consistently applied from thereon in. Under Title VIII, the Civil Rights Commission was charged with determining whether patterns or practices of discrimination existed in voting and voter registration.

Title II: Outlawed discrimination based on race, color, or religion in public accommodations such as movie theaters, restaurants, and motels involved in interstate commerce. Private businesses, such as social clubs, were excluded from this provision.

Title III: The most controversial section of the bill, it prohibited state and local governments from discriminating in public facilities. Furthermore, it allowed the Attorney General to file suit in a federal court on behalf of those whose access to public facilities was denied or restricted on the basis of their race, color, or religion. This provision was viewed by many on the state and local level as a blatant overreach of the federal government. It was stricken from the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, but its inclusion in 1964 protected the rights of protestors against suppression of their First Amendment rights.

Title IV: Called for the desegregation of all public schools and the ability of the Attorney General to file lawsuits to enforce integration efforts.

Title V: Continued the Civil Rights Commission established in the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the responsibilities of which included investigating, reporting on, and making recommendations on civil rights issues affecting the nation.

Title VI: Prevented discrimination by government agencies receiving federal funding to the extent that funding could be terminated if compliance was not met.

Title VII: Equal Employment Opportunity Commission established to enforce the provision prohibiting discrimination by employers on the basis of race, color, religion, and sex. Those aligned with the Communist Party were not covered under this provision.

Title VIII: Under the Civil Rights Commission, voting and voter registration statistics would be compiled in designated areas in order to ensure that discriminatory practices, such as arbitrary application of voter registration tests, did not continue.

Title IX: Ensured a fair trial for all by making it easier to move civil rights cases from state to federal courts, when evidence of judge or jury prejudice exists. This provision was essential in guaranteeing that civil rights activists especially were not discriminated against during trial.

Title X: Established the Community Relations Service to mediate racial issues at the state and local level.

Title XI: For those accused of aforementioned civil rights abuses, Title XI granted them the right to a jury trial and for penalties not to exceed $1,000 or six months in jail.

The passage of this historic bill, initiated by President John F. Kennedy and fought for by so many others, laid the groundwork for subsequent civil rights legislation, setting precedence for anti-discrimination laws based on sex, age, disability, and more. As President Lyndon B. Johnson stated after signing into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, “…those who began America knew that freedom would be secure only if each generation fought to renew and enlarge its meaning.” As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of this landmark bill, let us remember all those who fought against oppression and injustice to secure the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all Americans.

[…] resisted moving on civil rights legislation in the first two years of his presidency, finally sent a bill to Congress after activists such as Martin Luther King Jr. had exposed to the nation, through […]

[…] for Jobs and Freedom (pictured above) made it clear to Kennedy that it was time to act. In an address to Congress, he asserted that America must fight for the liberty of all citizens “above all, because it […]