(This post was published on our previous blog on 4/18/2015.)

By Christina Fitzpatrick, Processing Archivist

During a project to update the finding aid for the Ernest Hemingway Personal Papers, we noticed several folders of “unidentified” incoming letters where the author was not known. Naturally, this piqued our interest and we decided to do some sleuthing. In the current age of online search engines and digitized records, could we finally identify some of these mystery writers? Here are two examples of how we researched the unidentified letters.

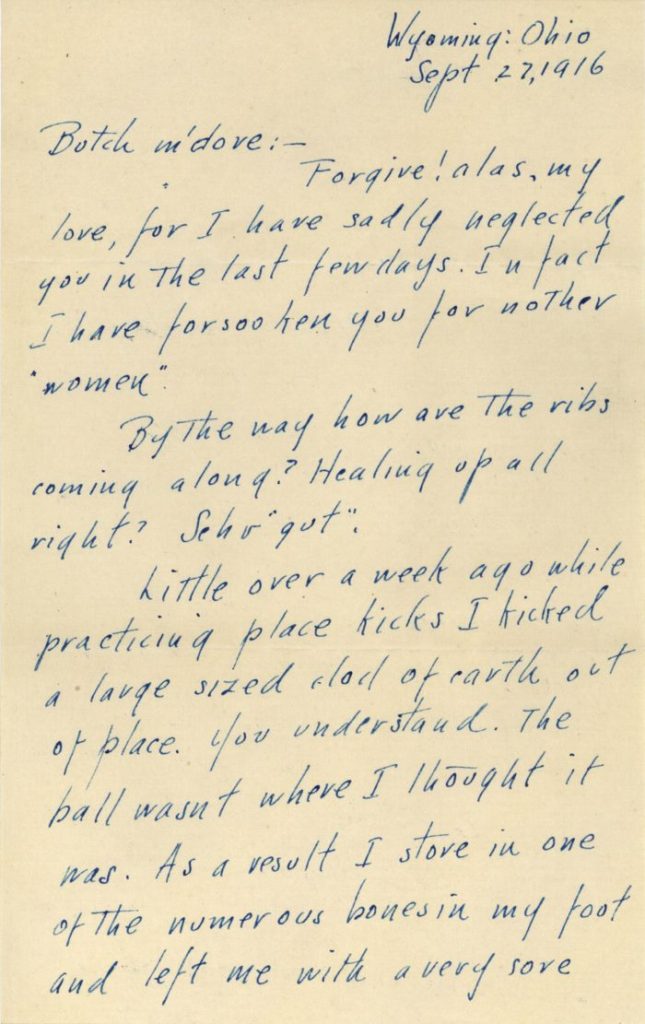

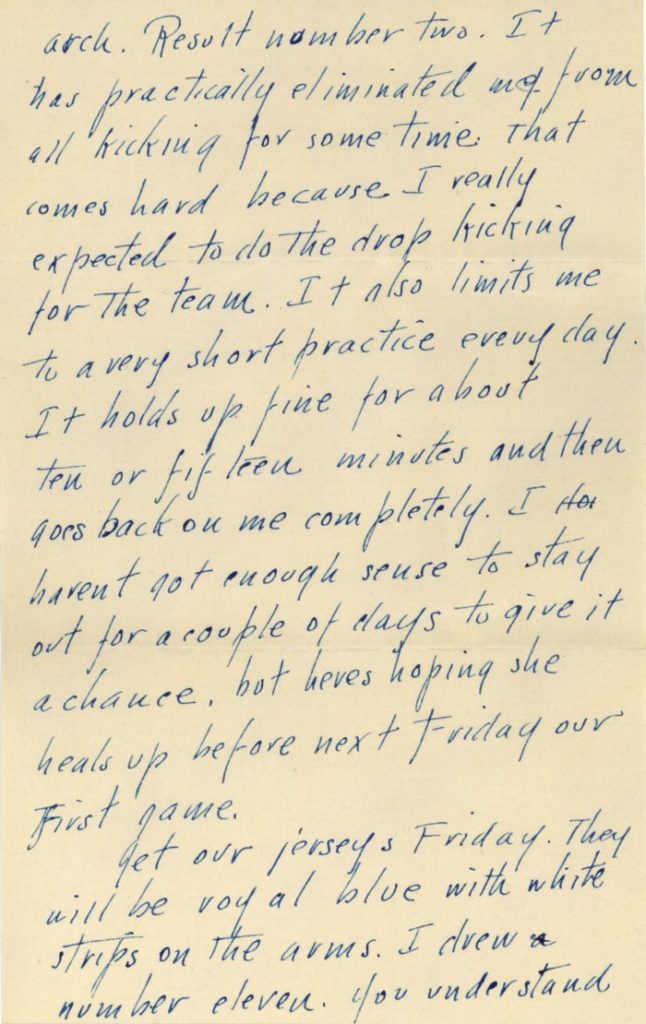

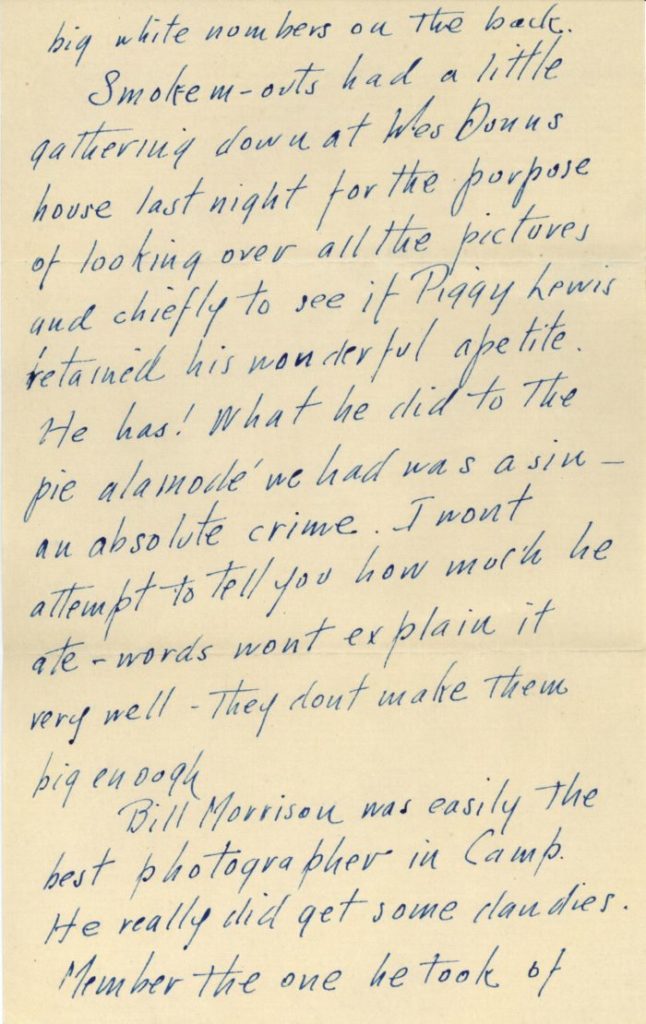

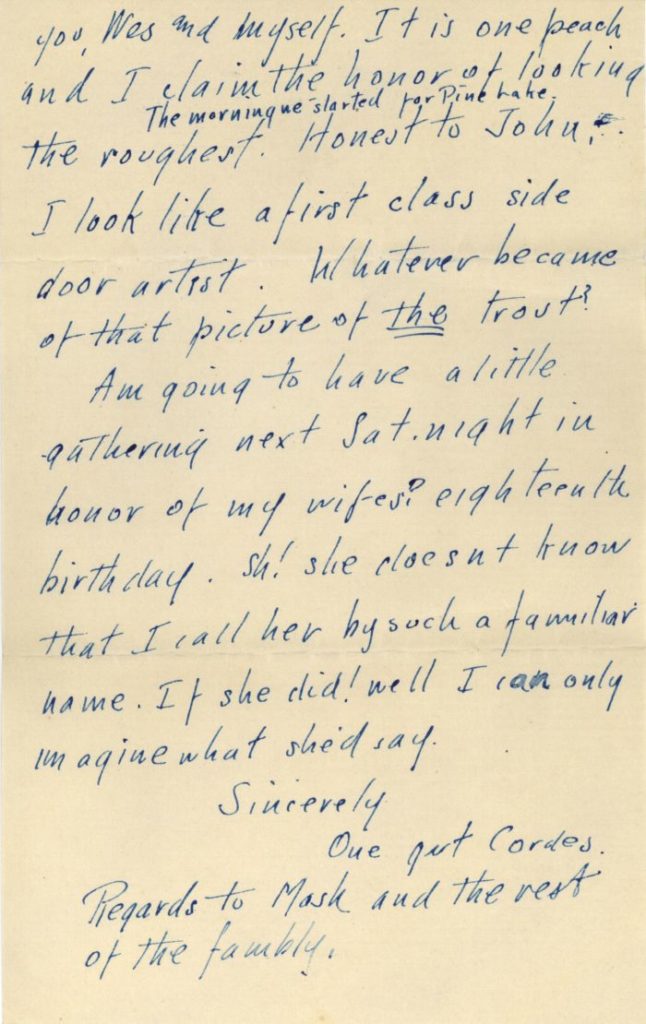

Case #1: “One gut Cordes”

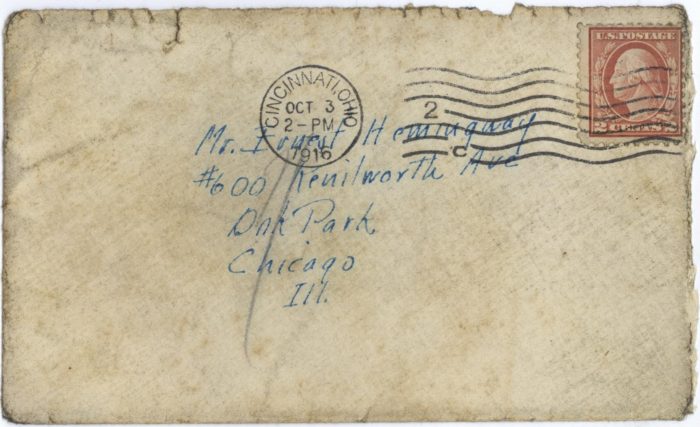

Ernest received two letters from someone who signed as both “One gut Cordes” and “Bill.” The writer was kind enough to include full dates (27 September 1916 and 16 October 1916) as well as a location: Wyoming, Ohio. Both letters were accompanied by their mailing envelopes, revealing a return address of 715 Springfield Pike, Wyoming, OH. In the letters, the writer discussed football, camp, and girls, leading us to think that he was probably a young man around Ernest’s age.

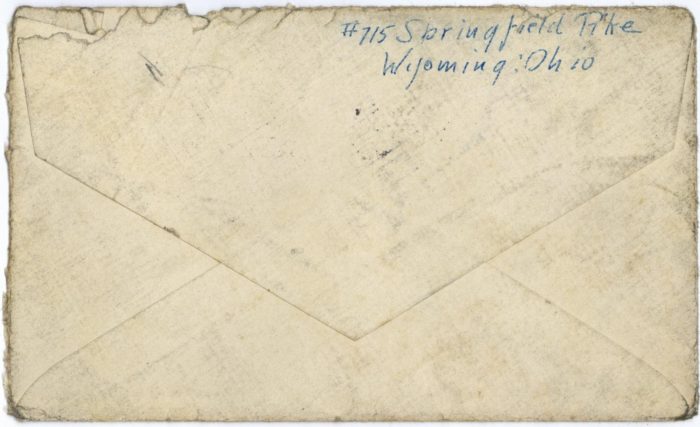

With these clues in hand, I headed to the 1910 United States Federal Census records held by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) and digitized by Ancestry.com. [1] A quick web search revealed that the town of Wyoming is located in Hamilton County, Ohio. After setting those geographic parameters, I started to browse the digitized census pages. Unfortunately, only one page was indexed under Wyoming and it did not contain the correct street address. I did notice that Wyoming was a division of Springfield Township, so I went back and selected the census pages for Springfield, Ohio. Fifteen enumeration districts were listed under Springfield, with the added information that six of them covered “Wyoming village.” I scrolled through the pages for these six Wyoming districts until I found the residents of Springfield Pike, then house number 715. There they were, the Cordes family! So “one gut Cordes” did in fact refer to his surname. The family included a son, William A. Cordes, who was 10 years old in 1910. This meant he was born around 1900, only a year after Ernest – and it makes sense that he signed one letter with the nickname “Bill.” I knew I had found my mystery writer.

In retrospect, I could have made some assumptions to get to the information more quickly. Searching the 1910 census for the name William Cordes, born around 1899, living in Wyoming, Hamilton County, Ohio, does in fact lead you to the same person. This may not always work, but employing some educated guesses is always a good tactic to use when searching census records.

[1] Access to Ancestry is free-of-charge and unlimited from any National Archives facility.

Case #2: Charles from the Gripsholm

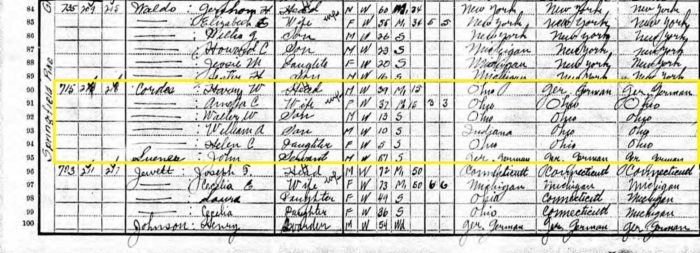

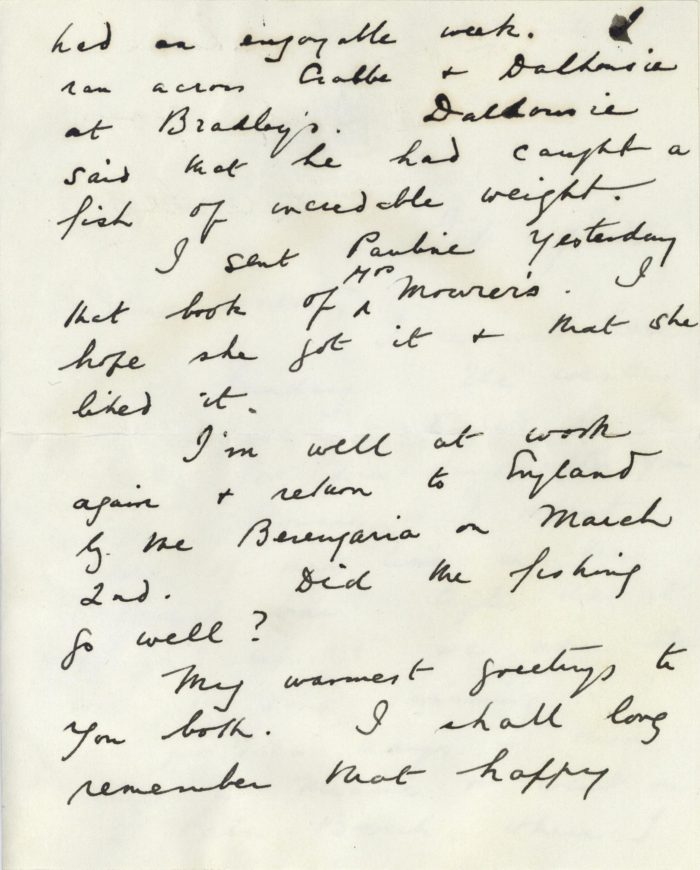

Ernest received this letter written by someone named Charles on 17 February 1938. Our archives intern, Bonnie McBride, tackled the detective work for this item. She found many clues in the content of the letter itself. Charles wrote:

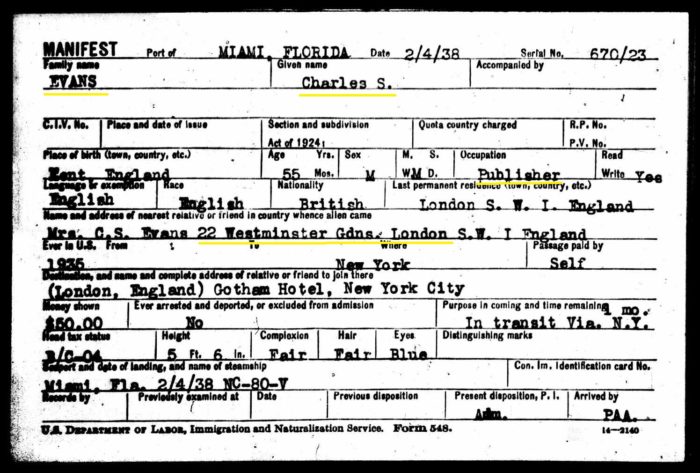

The weather at Nassau continued to be filthy for four days after you left. Ronnie and I spent most of that time in the Colonial bar. … I ran across Crabbe and Dalhousie at Bradley’s. … I’m well at work again and return to England by the Berengaria on March 2nd. … My warmest greetings to you both. I shall long remember that happy trip on the Gripsholme [sic].

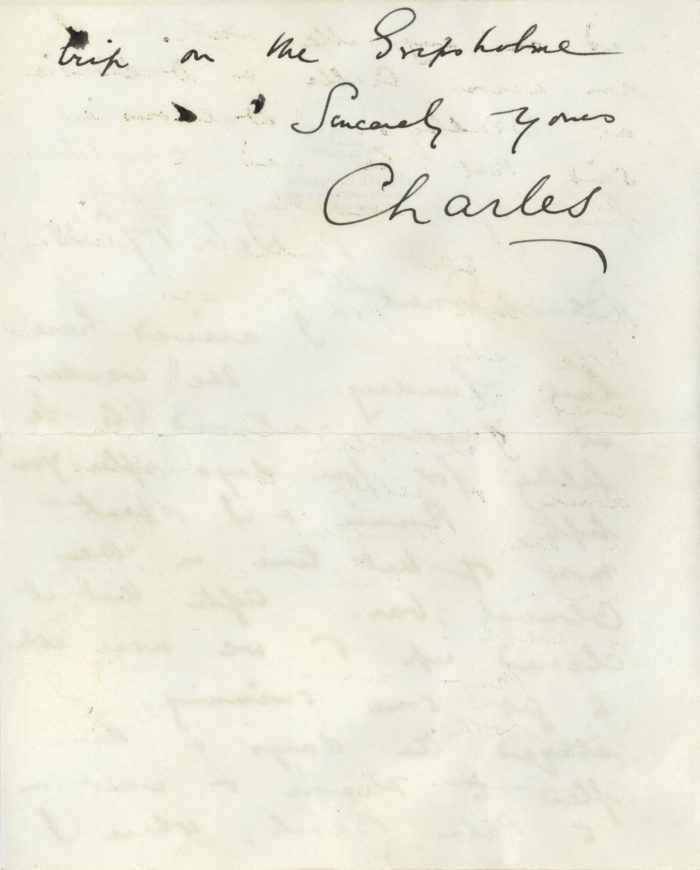

Bonnie started by going to Ancestry.com and finding the category for Immigration and Travel records. After selecting Passenger Lists, she searched for the name Ernest Hemingway, born in 1899, and destined for Nassau, Bahamas. The first result was a page from the UK Outbound Passenger Lists, which documents that Ernest left Southampton, England, on 14 January 1938 aboard the ship Gripsholm, which was bound for Nassau. Bonnie scrolled through the passenger manifest for this voyage, and located two British citizens named Charles: Charles H. Caves, listed as a 54-year-old manservant from Newton Mearns, Scotland, and Charles S. Evans, a 49-year-old executive from London, England. She also found the other men mentioned in Charles’s letter: Archibald Crabbe, Earl John G. Dalhousie, and Ronald Banon (who could be “Ronnie”). Based on this evidence, Bonnie strongly believed that our writer was Charles S. Evans.

I decided to try to find a record of Charles returning to England on the Berengaria on 2 March 1938, as he mentioned in the letter. Another search of the ship passenger logs revealed that the Berengaria arrived in New York on that date, but then it disappeared from the records. A quick web search revealed that the Berengaria caught fire in New York harbor on 3 March! The damage was serious enough that the ship was immediately taken out of service; it was scrapped later that year. Thus Charles had just missed the final voyage of the Berengaria and had to find another way home.

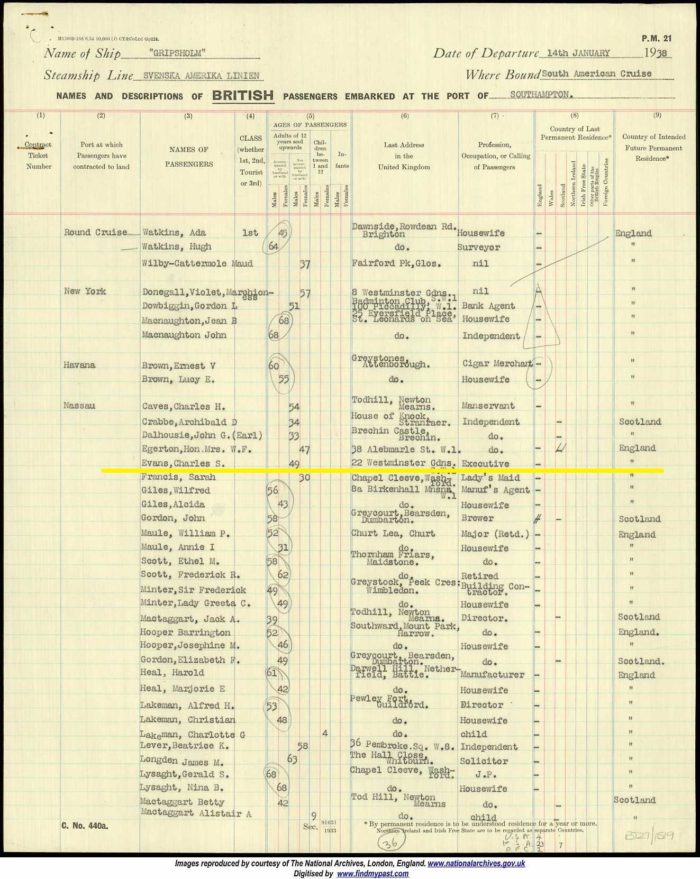

I had quite a bit of trouble locating Mr. Evans again. Going on the assumption that he was born around 1888 – to narrow down the many people with the surname Evans – I initially did not have any luck locating him on return voyages to England. Finally I searched all the passenger lists for any Charles S. Evans arriving in 1938, anywhere. This brought up a Charles S. Evans, age 55, who arrived in Miami via airplane on 4 February 1938. This fit with the letter because Charles wrote that he “flew to Miami” after the stay in Nassau. In this record Charles was older and described as a publisher, but he provided the same home address as in the Gripsholm manifest. At this point, I was sure he was the same person.

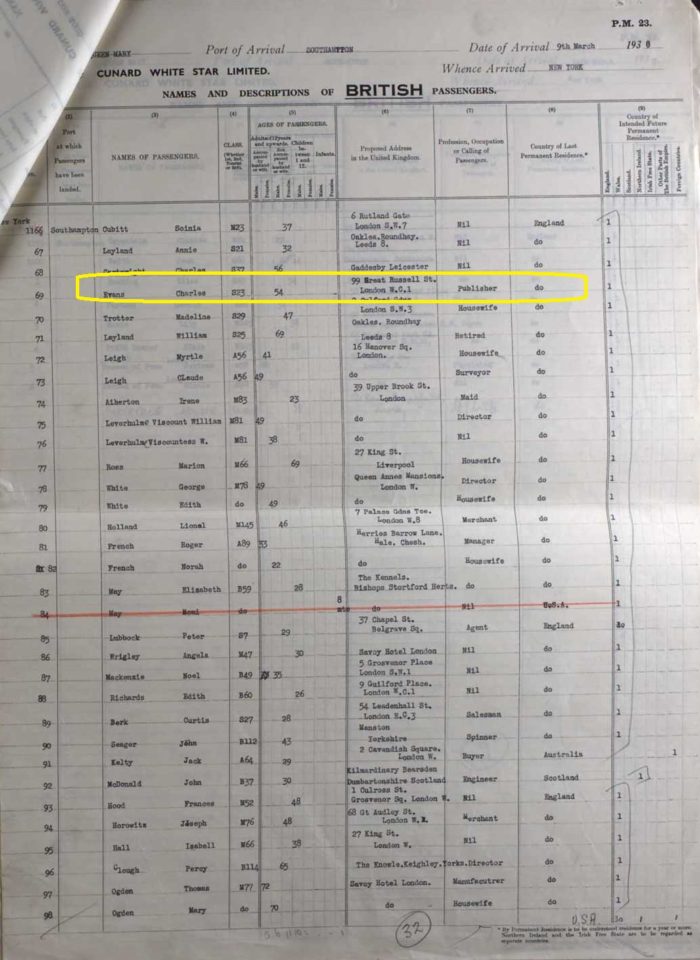

Using his new birth year of 1883, I tried searching the passenger lists again. This time I found Charles S. Evans, age 54, who departed New York on the Queen Mary and arrived in Southampton, England, on 14 March 1938. He was listed as a publisher and gave an address of 99 Great Russell St., London WC1. I checked the London city directories and found that West Magazine had offices at that location, so it appeared this was his work address. With this new information in hand, it was easy to imagine why Ernest the writer and Charles the publisher got along so well on their “happy trip” on the Gripsholm.

Moral of the story? If you hit a wall in your research, be sure to try many different combinations of any personal data you have on your subject. Some records can be inaccurate or misleading. We’ll never know if the customs officer made a mistake – or whether Charles lied about his age!

[…] Archival Detective Work in the Hemingway Collection » […]

This is very important for notify the quality of record, may be to destroy or to maintain for future.