(This post was published on our previous blog on 11/3/2015.)

By Niall O’Leary, Digital Humanities Specialist (guest author)

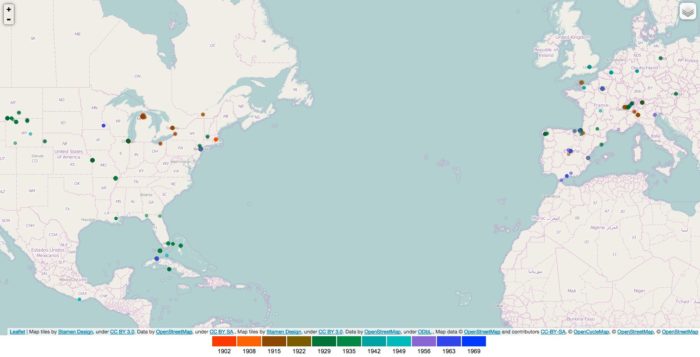

Ernest Hemingway traveled a lot. Really, a lot. Born in Illinois, he first left the United States for Europe to become an ambulance driver in World War I. He returned to the U.S., then went to Canada, then France, and after that his travels really took off. This is clear from any Hemingway biography you might pick up, but it is also clear from a single image; this one:

The map shown above is created using information about the letters Hemingway sent throughout his life. The assumption is that if he sent a letter from a location then there is a good chance that he must have been there when the letter was sent. This map uses colors to indicate the time Hemingway was in a certain place; the closer to red along the spectrum, the older the letter, the closer to blue, the more recent.

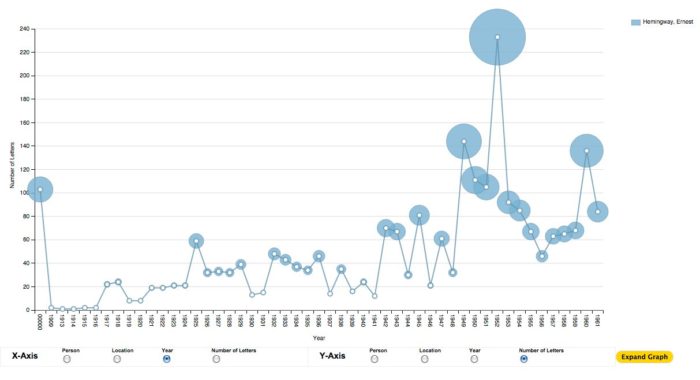

This kind of visualization is a useful tool when conceptualizing large amounts of data (in this instance, nearly 2,500 letters). Data visualization transforms many thousands of complex items into simple graphs, charts, and maps that make it easy to appreciate certain aspects of the original objects. For instance, letters are often deeply personal, semantically rich records of feeling, ideas, and personality. Studying even one letter’s content can require specialist skills, while ambiguity, typos and basic individual style can complicate even the most detailed reading. Yet every letter has a set of attributes that once known makes it possible to compare one letter with another. These standard characteristics are a source of relatively unambiguous information and tell us about the letter itself rather than its content. As we have seen, just knowing where a letter came from provides a very important piece of information in itself. There are other characteristics that also illuminate correspondence and by extension the correspondents involved. For example, who sent a letter, who they sent it to, where they sent it and when, are details that allow correspondence to answer a whole host of questions about historical figures and their worlds.

In the case of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library’s holdings, the Ernest Hemingway Personal Papers provide a wide range of opportunities for scholars studying the great writer. Scrapbooks, clippings, letters, notebooks, published and unpublished manuscripts all jostle for one’s attention among the treasures. Just how does one get a handle on so much data? How can one possibly navigate, let alone study, all this material? In the case of his correspondence alone, there are over 10,000 letters both from and to Hemingway and his family. Most of this material is held in its original paper format. Only the most tenacious researcher with a huge amount of time on their hands and working within the Library itself could possibly rein in even a portion of such holdings. Unless they use data visualization, that is. Luckily the Library has documented their extensive holdings in a hugely detailed finding aid available online as a Guide to the Ernest Hemingway Collection. While this document contains detail on thousands of objects, it usefully brings together the most salient metadata in one place. Extract this metadata digitally, apply current technology, and some aspects of the collection can be navigated, analyzed, and understood. To be sure, we cannot answer all questions about Hemingway, but with relative ease we can now provide answers to many queries that in the past might have been beyond our time and resources.

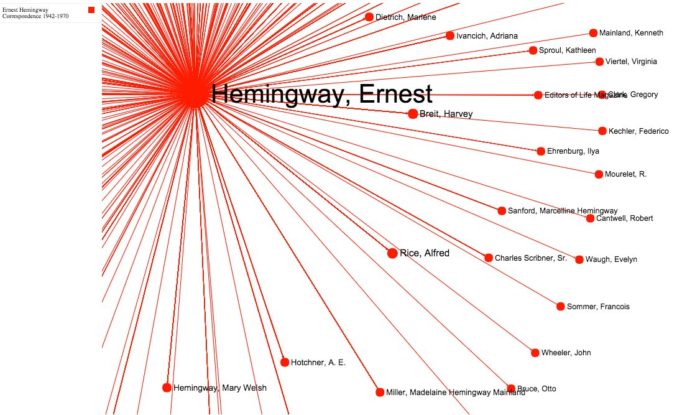

For instance, who did Hemingway write most of his letters to? (His last wife, Mary Welsh Hemingway, received nearly 11% of his letters.) Who wrote to him the most? (His first wife, Elizabeth Hadley Richardson, takes that honor.) Which other writers and artists was he in contact with? (A huge network included F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson, and Marlene Dietrich among many, many others.) How did the nature of his correspondence change as his popularity grew? (His letter writing peaks around the time he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.) Where was he in early March 1952? (Hemingway was at his home in Cuba while finishing his Pulitzer Prize-winning, The Old Man and the Sea.) To be sure, the where, when, and who questions are not always as interesting as the why, but knowing their answers often provides a clue when addressing motivation and cause. To the biographer or the Hemingway scholar, the who, when, and where questions are crucial.

It was with a view to exploring these questions and seeing how far the barest data might take us, that I developed the website ‘Visual Correspondence’. This site takes the five elements I have mentioned – sender, recipient, origin, destination, and date – and provides the user with a wide range of tools for querying that metadata. Maps, pie charts, bubble graphs, timelines and many more visualizations allow a user to conceptualize thousands of letters through a few clicks. As well as developing these tools, I have also sought out as many collections of letters as I could find and tried to index their metadata. That was how I came across the Library’s excellent finding aid. At the time of writing, I have indexed nearly 160,000 letters from thousands of writers, scientists, politicians, and artists, not to mention so-called ‘ordinary’ people, with correspondents such as Mark Twain, Charles Darwin, Benjamin Franklin, and James Joyce rubbing shoulders with immigrants, factory workers, and civil servants. My hope is that in bringing together so many disparate collections, overlaps and outliers might become apparent leading to new scholarly insights. At the most basic level the site provides a means of finding letters that even the most sophisticated Googling might not bring to light.

So what does ‘Visual Correspondence’ tell us about Ernest Hemingway. Certainly it confirms a lot of preconceptions. That he traveled extensively, had many friends and lovers, and became a cultural icon for the global literary community is clear through an analysis of his network of correspondents. That he was closely involved in his business affairs (he wrote extensively to his lawyer, Alfred Rice), that his various wives were in contact with one another, and that his interest in politics continued throughout his life (there is even some contact with John F. Kennedy) is also abundantly clear. However, the real insights are yet to be found and will require good old-fashioned research, albeit research with a new set of tools. What is certainly clear to me is that without the excellent finding aid compiled by the John F. Kennedy Library none of this would be possible. In his Nobel Prize-winning speech, Hemingway wrote, “A writer should write what he has to say and not speak it”. Thankfully for us, he was a true writer.

Thank you, Niall, for taking this information and thinking about it in a new and exciting way. It’s impressive! Keep up the good work.

This is a very fine resource for Hemingway specialists, but also helps the rest of us to think about correspondences differently. Well done!

[…] Image credit: Earl Theisen, LOOK Magazine, John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston, viewed 3 Aug 2016, <http://archiveblog.jfklibrary.org/2015/11/visualizing-hemingway-a-man-in-letters/ >. […]